Introduction

The Style Empire (c. 1800–c. 1820) offers a particular challenge for any attempt to bring style back to the agenda of architectural history. Its major surviving monuments display a mix of historical styles, mainly Greek, Roman and Egyptian, and a taste for shining, precious materials combined with a rather oppressive Imperial iconography. It is the last attempt to create a new French court style, devised consciously, like the court ceremonial Napoleon reinstated, as a successor to the styles of the Bourbons, and as doomed as his attempt to refound the Roman Empire. At first sight this does not make it a particularly appealing or even interesting case of style formation. But when one takes a closer look, Empire furniture, interior design and architecture turns out to be much more than a rehearsal of Greek, Roman or Egyptian designs. They are rejuvenated by the discovery of Herculaneum and Pompei, and nourished by Piranesi’s widening of the range of formal repertoire to include Etruscan, Republican Roman or Egyptian forms. The Empire style also announces 19th-century neo-styles and historicising eclecticism in its systematic combination of design styles and forms from different periods and places, both European and non-European, in one piece, one interior or one building. The formation of this style therefore offers particularly rich avenues for exploration, and to understand the reasoning behind choices to appropriate Egyptian and Graeco-Roman elements, transform them in new materials, and use them in new combinations, for new functions and settings. The famous washstand, or Athénienne, designed by Charles Percier and executed by Biennais for Napoleon, for instance, is a transformation, in gilt bronze, silver and yew wood, of a design etched by Piranesi, which in its turn was a transformation of a tripod depicted in a Pompeian ‘Alexandrian’ landscape, but with the addition of swans and dolphins, a Greek running dog motif bordering the silver basin, and Egyptianizing lion claws (Figures 1, 2, and 3).

Athénienne, design attributed to Charles Percier (1764–1838); mounts gilded by Martin-Guillaume Biennais, 1764–1843 (active ca. 1796–1819), 1800–14; legs, base and shelf of yew wood; gilt-bronze mounts. Metropolitan Museum, Bequest of James Alexander Scrymser, 1918. Photo: Metropolitan Museum.

To move away from traditional appraisals of this style as imitations and emulations of Greek and Roman models, and to develop instead an analysis that concentrates on composition, I propose to take a fresh look at the pedigree of the Style Empire, because this self-consciously historical style was part of the successor culture of Napoleonic Paris. The Empire style was developed to a large degree as part of Napoleon’s conscious fashioning of himself, his rule and his city as the successor to Rome. Where Augustus wanted to transform the brick city he had found into one of marble, Napoleon once observed that he intended to solidify the revolutionary state built on sand by covering it with granite (Dansette 1969: 206–8). The starting point is one of the best-preserved Empire monuments, the Hôtel de Beauharnais in Paris (Hammer 1983; Pons 1989; Pillepich 1999–2000; Gaehtgens, Ebeling and Leben 2007–8; Ebeling and Leben 2016). After a brief discussion of its design, now attributed to Charles Percier and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine, I will turn to its ancestry in the work of Piranesi, his creation of new Roman antiquities and the composition principles he evolved in their making. Next I will propose as formal and compositional models for his work the architecture of Hellenistic Alexandria and Petra, and its representation in Pompeian wall painting. Finally, I will argue that what is usually called revivalism or historicism in the case of neo-classicism or the Empire style can be much better understood when considered in terms of compositional techniques as developed in Alexandria and the Hellenistic world. These were taken up by Piranesi, who was very familiar with these as represented in the mural paintings of Pompei and Herculaneum, and taken further by Percier and Fontaine as part of the conscious attempt of a successor state to recreate a visual and material pedigree.

The Hôtel de Beauharnais in Paris

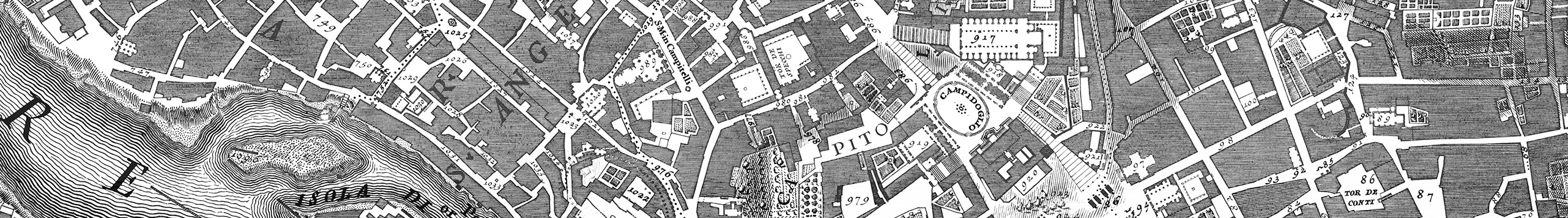

The Hôtel de Beauharnais started life as an early Regency town house, designed by Germain Boffrand (1667–1754), who sold it in 1713 to Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Marquis de Torcy, the eldest son of Louis XIV’s prime minister and himself minister of foreign affairs from 1695 to 1715 (Ebeling and Leben 2016: 25–69; Hammer 1983: 9–45; Boffrand 2002). It was one of the first hôtels particuliers to be built in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, and it changed owners several times during the eighteenth century, ending up, after 1789, in the possession of two speculators, A.P. Bachelier and P.-J. Garnier. As the images in Jean Mariette’s Architecture Française, published in 1727, show (Figure 4), it was a typical Parisian design of the Regency period of the variety that Boffrand did much to develop, while still adhering to the traditional enfilade lay-out of rooms (Blondel 1752–56: vol. 1, 182; Brice 1725, vol. 4: 148; Brice 1752: vol. 4, 139). Not much remains of the original state, except the basic layout of the staircase and the outside walls.

After a spell during the Revolution when the house was owned by the speculators Bachelier and Garnier, when most of its 18th-century decoration was removed, Eugène de Beauharnais (1781–1824), Napoleon’s adopted son, acquired it in 1803. He began to live in it in 1804, and had it entirely redecorated. Because of the excessive costs of the redecoration, in 1806 Napoleon took the building from Eugène, and from 1809 used it to lodge important guests. The house was sold in 1818 to Friedrich Wilhelm III, the king of Prussia; since then it has remained in German possession, becoming the residence of the Prussian, and subsequently the German, ambassador. In the past decade much effort has been made to recover the original furniture and to restore the interior to the way it looked during the rule of Napoleon.

Its redecoration was based, we now know, on the plans by Napoleon’s architects, Percier and Fontaine, who had studied in Rome and had been very close students and followers of Piranesi’s work, his compositional strategies and interior design (Garric 2017). Joséphine, Eugène’s mother, oversaw the building works and was probably also involved in many of the decisions.

On the ground floor the main changes made for Eugène include the replacement of the court portico by a stucco Egyptian temple portico, generally thought to be inspired by the portico in Denderah (Figure 5); the introduction in niches along the stairs of two life-size statues of Antinous, based on the statue found in Hadrian’s Villa, and attributed to Pierre-Nicolas Beauvallet, which entered the collection of the Musée Marmottan in 1935 (Leben and Ebeling 2005: 70); the Salon Vert of Egyptian inspiration; and the large room functioning as picture gallery and ball room, to the right of the entrance hall, which was decorated with green hangings bordered in the ochre colour known as ‘terre d’Egypte’. Egyptian and Egyptianizing objects were scattered throughout the hôtel: for instance, a chimney decorated with elements from the Mensa Isiac, a porphyry obelisk and gilt candelabra with Nubian women holding up the candles.

The replacement of Boffrand’s flat portico by an Egyptian feature was part of a campaign to scatter Egyptianizing monuments across Paris, a campaign that was also to include six fountains (only the one in the Rue de Sèvres by Bralle et Beauvallet survives), an Egyptian temple and an obelisk on the Pont Neuf, and to introduce reliefs of Isis, designed by Jean-Guillaume Moitte, in the pediments of the Cour Carré in the Louvre (Humbert 2009: 274; Hubert 1972; ‘Du haut de ses pyramides …’, 2013–14).

In Van Eck and Versluys (2017) Miguel John Versluys and I have presented a much more detailed analysis of the immersive character of this building and the cultural memory created by the biographies of its Egyptian elements. The present essay concentrates on the problem of the poetics of eclecticism outlined there.

The Grand Salon, now called the Salon des quatre saisons, replaced the large gallery that originally ran along the entire garden front. Three large paintings by Hubert Robert, representing Tivoli, were replaced by four allegories of the seasons, attributed to the studio of Girodet-Trioson (Figure 6). Eugène’s bedroom is probably based on a design by Percier and Fontaine for a stage back-drop for Psyché (1793). Next to it, the bathroom is an illusionistic space with mirrors sending each other their reflections (Figure 7).

The larger-than-life paintings of the seasons and muses add to this atmosphere of illusion, since they are very similar, in the way they seem to come forward from their hazy background, to the way figures appear and take tangible form from a background of smoke and gauze in phantasmagorias and other multimedial shows, a new theatrical genre that was born at the same time as the Empire style (Warner 2006; Sawicki 1999). The figure of Winter in the Salon des quatre saisons, for instance, seems to move weightlessly in a mysteriously lit space, where a lamp seems to shine behind a veil of gauze. But they also recall, in their combination of a dark uniform background from which a figure appears to advance in a completely weightless manner, the wall paintings published in the first volume of the Pitture antiche d’ercolaneo e contorni (1757, vol. 1: plates XIX and XX).

The overall impression created by the Hôtel de Beauharnais is that of a dazzling series of interiors, in which vivid blues, red and greens are displayed on a background of terre d’Egypte ochre with black borders. The glossy silk that reflects daylight and the many candles lit at night contrast with the background textiles that absorb light instead of reflecting it. The newly restored interior strikes the visitor above all with the sheer effect of its brilliance. The light bounces off the gilt surfaces of the bronze appliqués that are scattered over tables, beds, chairs, chimneys and wash stands; the gilt stucco mouldings of friezes running along walls, ceilings and doors dematerialize their material supports.

Once one starts to look more closely at the details of ornament and mouldings, it becomes clear that what appears at first sight to be a repetition of Roman or late 18th-century ornament, is in fact a much freer transformation of it. The classical orders, for instance, play a far less prominent role as the main generators of ornamental forms than in designs by Boffrand, his contemporaries, or successors like Jean-François Blondel. In interior design between 1750 and 1790, most conspicuous ornaments can easily be traced back to an element of the orders (capitals, friezes, mouldings and modenature such as egg-and-dart mouldings), and combinations of elements from different orders in one ornamental feature would rarely occur. Here, however, ornament often combines Greek, Roman, Etruscan and Egyptian elements, and it is derived not from the orders, but from ancient furniture: from tripods, sarcophagi, funerary urns, statuary, or lamps. The gilt frieze running below the ceiling in the Salon des quatre saisons, for instance, integrates eagles, palmettes and festoons within a transformation of an egg-and-dart moulding.

This brief examination of the Hôtel de Beauharnais suggests the following characteristics of the Empire style. First, it consists of a rehearsal or appropriation of Graeco-Roman and Egyptian forms that, on closer inspection, turn out not to be based on the traditional schema of imitation and emulation as advocated by the French Académie in the 17th and 18th centuries, and which is still considered by some to define the work of Percier and Fontaine (Garric 2017). Different materials are used in recreations of ancient prototypes, such as the Roman metal tripod transformed into a wooden and silver Athénienne mentioned above. The composing elements taken from different ancient sources are combined in different ways: Corinthian tendrils, acanthus palmettes, sphinxes and grotesques inspired by the Loggias in the Vatican, in their turn based on the grotesques in the Domus Aurea and also found in Alexandria and Petra, are combined, in a very typical instance, in the gilt mouldings decorating the entablatures of the Salon of the Four Seasons (Figure 6). There is also an insistent presence of animal forms: feline legs supporting tables and chairs, and sphinxes, swans and dolphins are scattered across the interior, cropping up in the most unexpected places, in a frequency and variety that far surpasses zoomorphism in 18th-century French or classical Greek architecture.

Hence the most conspicuous departure from Graeco-Roman or Egyptian models is that Empire style objects simply do not look like their predecessors. Materials that are much more glittering and shining create a very different first impression. Heterogenous elements are combined: candelabra sport pedestals with pseudo-hieroglyphs and Isiac symbolism, but naked Nubian women also support the candle-bearing branches that combine acanthus tendrils sprouting into secondary grotesque figuration (Figure 8). And finally, the nature of the appropriation of antique forms is also not the same as previous revivals of Graeco-Roman art and architecture. Instead of attempting to imitate and recreate these forms as faithfully as possible, ancient prototypes are now appropriated and transformed. To cite again the Athénienne designed for Napoleon: it begins, on paper, as a recreation by Piranesi of a tripod depicted in a so-called Alexandrian landscape in Pompei, and then is materialized, after a design by Percier, by the goldsmith Biennais, in wood, silver and gilt bronze, keeping the original outline, but removing the goat’s legs, and adding swans, dolphins and a silver basin.

The Pedigree of the Empire Style

The major artists involved in creating this style were notoriously silent about their work, as were patrons and users, except for the occasional telling comment. Thus Pierre-Louis Roederer commented in the Journal de Paris of 1801 on the wealth of ancient sources employed: ‘Tu ne connais pas le prix de tes meubles…. Plus de dix mille estampes, de cinq cent médailles, de deux cent camées ont été mis à contribution pour former ce beau tout’ (Samoyault 2009: 39).

But the designs themselves suggest a definite ancestry, rooted in Piranesi’s life-long attempts to recreate, in etchings and, at the end of his life, in objects as well, the presence of ancient Rome. Percier and Fontaine greatly admired his work and must have been familiar with Piranesi’s museo, his collection of antiquities, restorations and original artefacts in his house on the Via Tomati. Even after the sale in 1784–85 of a large part of the collection to the King of Sweden, substantial parts remained on view in Rome (Panza 2017: 42–45). For one of his envois Percier prepared a graphical reconstruction of the Column of Trajan, the monument Piranesi had etched at the end of his life in a very large plate measuring more than five metres. In his own reconstruction, Percier follows Piranesi’s interest in crowded compositions consisting of arms, trophies and sacrifical instruments, which Piranesi also displayed in Santa Maria del Priorato (Raoul-Rochette 1840: 246–68; Frommel et al. 2014). Objects made by Piranesi are reproduced in Percier’s designs, such as the colossal candelabrum Piranesi had designed for his own tomb, and which Louis XVIII eventually acquired for the Louvre, where it remains. Also, the rhyton ending in a boar’s snout included in Piranesi’s last printed collection, Vasi, candelabri e cippi of 1778 reappears as a gilt bronze appliqué on a writing cabinet executed by Georges Jacob and François-Honoré Georges Jacob-Desmalter, now in the Philadelphia Museum. The winged lion legs supporting a vase or table, depicted in Vasi, candelabri, cippi, plate XXXI, materialized in the Trentham Leaver vase now in the British Museum, were also often incorporated by Percier and Fontaine (Garric 2017: 181, fig. 8A.3; Panza 2017: 65).

There is also a striking similarity between the composition and layout of objects in Piranesi’s collective views of Roman antiquities, for example in the first frontispiece to the Antichità romane (1756; Figure 9). They all look like idealized open-air musea displaying Roman architectural fragments, statuary, tombs, altars and parts of the orders, and there is the same mixture of Greek, Roman, Etruscan and Egyptian elements, with a strong preference for ornament, animals, trophies, and armour; and an equally evident absence of the canonical and the useful. Both in the Antichità and the Edifices et palais de Rome artefacts from the Imperial, in particular the Hadrianic, period dominate. The younger artists also follow Piranesi’s compositional strategy of including as many artefacts as possible, either ordered in receding picture planes suggesting vast spaces, or in overlapping strata that suggest the depiction of a sculpted relief like the pedestal of Trajan’s Column.

Piranesi on Composition: Opere romano

Unlike his French admirers, Piranesi did leave some statements about his working methods. He made some observations about the design of the colossal candelabrum in the Louvre, which Percier later depicted in one of his designs. In Vasi, candelabri and cippi he included etchings of all three colossal candelabra he had made from the fragments of Greek, Roman and Egyptianizing statuary Piranesi had excavated in 1769 from the swamp of Pantanello near Tivoli. In the 1770s he turned from his graphical work to creating these objects, exhibiting them in his museo, and sometimes selling them for staggering sums (Penny 1992, vol. 3: 108–16). In his comments he claimed that they were genuine Roman artefacts: ‘opere romane’, as he put it.

The design of all three candelabra follow the same basic scheme (Figures 10a, 10b, and 11): a pedestal consisting of three legs, in which lion claws grow into acanthus leaves, or as in the one now in the Louvre, into a lion’s head biting into the lower leg. These legs support a carrying structure derived from Roman altars and display mythological figures and animals on the corners: griffins, tragic and comic fauns and masks or Medusa heads, and the birds on the lake of Stymphalos that were killed by Hercules. The transition between the pedestal and the shaft is articulated in the Louvre candelabrum by three rams’ heads, which support a column consisting of an almost postmodern bricolage of elements taken from the pedestals of columns, including tragic masks and fauns plucking fruit, another row of modenature taken from the Corinthian and composite order, and a bit of twisted Salomonic column, culminating in a series of leaves, lion heads and acanthus leaves that support the large basin that could carry burning wood or candles. In Oxford one candelabrum sports a shaft surrounded by another hybrid bird, part stork and part pelican. These birds in turn support the statue of a faun carrying the culminating vase in which wood or incense would be burned. Preliminary drawings and sketches survive, in the British Museum and in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York.

a (left): G.B. Piranesi, two marble candelabrum, h. 300 cm, made of various elements (Roman, 15th and 18th century), after a design by Piranesi. Acquired by Sir Roger Newdigate in 1774, donated to Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University, in 1775. Photo: Wikimedia Commons. b (right): G.B. Piranesi, marble candelabrum, 353 cm high, made of various elements (Roman, 15th and 18th century, after a design by Piranesi. Acquired from his estate in 1815. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo: author.

When we put Piranesi’s candelabra next to those surviving from Roman antiquity that Piranesi knew very well, such as the Barberini candelabra now in the Museo Pio-Clementino, it is striking to see how very different they are (Figure 11). The Barberini candelabra have a clearly visible structure of pedestal, shaft and light-bearing disc, derived from acanthus and Corinthian forms, and a quite sober and coherent iconography of gods and small Erotes. Piranesi’s work, however, presents a very riot of ornament, a profusion of elements taken from altars, the theatre, sarcophagi, and furniture, not to forget his tendency to duplicate and reverse classical motifs. In his candelabra the lion claws are not simply content to carry a pedestal, but their performance of this task is enlivened by sinking their teeth into their own claws.

Nonetheless, and despite the fact that Piranesi was well acquainted with the surviving Roman specimens in the Barberini and papal collections, he was quite emphatic about their provenance and authenticity. For instance, in the caption of plate 25 of Vasi, candelabri and cippi, the last collection of etchings Piranesi prepared, he describes the Pelican candelabrum as a ‘pezzo singolare di antiquità’. In the explanatory texts for the other plates depicting candelabra, he argues how, working from the fragments surviving from Pantanello, and using the classical composition principles as outlined by Vitruvius and others, chief among them symmetry, he does not restore, let alone recreate these ancient objects, but reconstructs them entirely in the Roman manner. About the stork candelabrum, now in the Ashmolean, he says, ‘Fu ritrovato fra le altre antichità nello scavo fatto l’anno 1769 nel sito detto Pantanello due miglia lontano da Tivoli posseduto della famiglio de Signori Lolli, ed era anticamente detto sito un lago appartenente alle delizie della Villa Adriana.’ That is, he repeatedly claims in the Vasi that he did not restore these ancient objects, but rather reconstructed them entirely in the Roman manner. Contemporaries, such as the British collector Jenkins, also repeated these claims: ‘The Cavalier of the Candelabri … amongst the other things has Composed a Monument for himself — his third Candelabri [sic] is completed, the which he sais, was found tale quale as well as the other two in Adrians Villa’ (Bignamini and Hornsby 2010, vol. 2: 8). These are all rather puzzling statements, because his candelabra do not at all resemble the surviving Roman specimens that Piranesi could have seen in the Barberini and papal collections.

So what is going on here? Are these candelabra authentic objects? Are they attempts at faithful reconstruction? New objects using a large degree of Roman fragments? Over-enthusiastic restorations? Or simply fakes? Until very recently this question could not be answered with any certainty, because we do not have sufficiently reliable records of what went on in his studio, or his museo, as he preferred to call it. Then something happened: Georg Kabierske, a young German intern at the prints and drawings collection at the museum in Karlsruhe, asked to see their collection of drawings of the local architect Weinbrenner. Kabierske discovered that these boxes contained in fact 260 drawings by Piranesi or his studio, many made in preparation for the artefacts he created after his excavation at Pantanello, and which he published in the Vasi, candelabri and cippi. They include a large red chalk drawing for one of the Oxford candelabra, which clearly shows that Piranesi may have integrated Roman elements, but the composition was very much his own.

So are we dealing here with false ingenuousness or with a genuine, ingenious talent for fabricating Roman antiquities, in the double sense of that word? Addressing this question will also throw some light on the poetics of eclecticism of the Empire style. Although Piranesi did not say much about the nature of these artefacts or of his design method, or about the reasons why he chose to produce such puzzling hybrids, there are some clues towards an understanding of his methods of composition in his two last major publications, the Diverse maniere and the Vasi, cippi e candelabri. In the text framing the stork candelabrum (plate 26), he wrote:

Veduta in prospettiva di un candelabro antico di marmo di gran mole. Si vede nel Museo del Cavalier Piranesi. Si rende pregievole per l’elegante varietà e idea dell’ intagli con finezza di gusto scolpiti, e sue sculture con leggiadra distribuzione à grottesco disposte, di maniera che non incombrano essi l’idea generale del suo tutto.

Varietà, finezza, leggiadra, grottesco: we seem to have entered here into the domain of ornament, in particular Pompeian and Rococo ornament, in which Piranesi excelled in his early career. Classical architectural theory does not give much help here. On plate 107, showing one of the candelabra intended for Thomas Jenkins, he added, ‘come una dell’opere le più perfette dell’antichità, non tanto per la mole e per l’architettura, quanto per la finezza dell’intaglio e per la diversità scolpite in ognuno del’ triangoli de’ prospettive piedistalli vi ho fatti presenti.’ That is, they are among the most perfect works of antiquity, not for their bulk and weight, nor for their architecture, but for the finesse of their carving and the diversità sculpted in each of the sides of the triangular pedestals. Here again, he is talking about the quality and nature of surface ornament.

Now if there is one place where he does talk about surface ornament at great length, it is in the introduction to his book on chimney ornament, Diverse maniere di adornare le cammini, published in 1769. The text is mainly known for its large-scale adoption of Egyptian forms and its polemical defence of Etruscan architecture as the cradle of classical architecture, but it also argues in favour of what we would now probably call stylistic eclecticism. According to Piranesi, the architect should draw not only on the remaining buildings of Roman antiquity, but also on the entire range of classical art: medals, intaglios, statues, reliefs, etc. Ornament, in other words, should be closely studied, and in particular the ways in which Egyptian and Etruscan ornament was transformed and adapted by the Greeks and Romans. In the Diverse maniere Piranesi shows how this was done. He begins with Graeco-Roman, Egyptian and Etruscan furniture and ornament and adapts it to a new typology, that of the chimney, a new genre of its own. Typical of what he calls la piccola architettura, and very close to furniture, this new genre calls for its own laws of decoration, and by its very dimensions prevents the automatic transfer of large-scale architectural ornament such as used in temple porticos, etc. A chimney is closer in fact to dress than to building, and made, like clothes, not just for usefulness, but for pleasure and enjoyment. Because of mankind’s innate pleasure in and desire for variety, the grotesque is also a fitting style for this kind of object, for its mixture of the serious and the gay, the frightening and the pathetic.

In this truly revolutionary text Piranesi not only opens up the range of styles to be used by the designer of chimneys and furniture; he also sets out the rudiments of a natural history of the architecture of the Mediterranean, and he tries to understand the laws governing its design, particularly that of the orders, by an analogy with shell formation (Hyde Minor 2015). All this is very helpful in giving some background to the variety of ornament in his candelabra, but one underlying issue is not addressed: how does one compose such heterogeneous objects? And what is their relation to their professed Roman models?

Whereas the Diverse maniere shows the forms and design concepts that Piranesi propagated, the arguments behind it are presented in the Parere of 1765 (‘Opinions on Architecture: A Dialogue’, in Piranesi 2002) and the rarely read essay, ‘Ragionamento apologetico in diffesa dell’architettura egizia, e toscana’, that serves as a preface to the Diverse maniere (Piranesi 1769). In the Parere, which is Piranesi’s sardonic attempt at Socratic dialogue, Piranesi’s spokesman develops a philosophy for designing ornament that breaks with the humanist tradition of ut poesis architectura and the proto-functionalist myths of Vitruvianism. Ornament is not the representation of the functions of various parts of the orders; nor is its composition determined by the same laws as poetical composition, because the eye can take in much more in one glance than the reader can grasp when reading a poem. Freedom, variety and invention are the main considerations; architects should allow themselves to be inspired by Roman Imperial architecture (Piranesi 2002: 33). Architects should therefore use the entire repertoire of forms from the age of Augustus and Hadrian: festoons, fillets, masks, heads of stags and oxen, griffins, labyrinth frets, arabesques, hippogriffs and sphinxes (Piranesi 2002).

In the ‘Ragionamento’ Piranesi extends this argument to all styles of ornament used in the Roman Empire, Egyptian and Etruscan as well. Here he also advocates the use of medals, intaglios, and cameos, artistic genres that are distinguished by their stylistic variety and geographical origins from all over the Roman Empire. These are all artefacts that in the Vitruvian tradition did not serve as the main models for the architect, because they are what would now be called hybrids. Again, decorum, tradition and attempts to reduce architecture to its tectonic essence are thrown out in favour of variety and, above all, invention: ‘Rome is certainly the most fruitful magazine of this kind’, he concludes in the ‘Ragionamento’, not least because Roman Imperial architecture integrated Egyptian, Etruscan and Greek or Hellenistic elements (Piranesi 1769: 12–33). The chimney designs that follow seem to present a stylistic riot of forms, but on closer scrutiny reveal a careful order in size and prominence. The various elements very often appear to grow out of each other; snakes transform into egg-and-dart mouldings that grow into capitals, and acanthus scrolls into grotesque figurations.

Another major ingredient of his transformation of that culture were the fragments he excavated at Pantanello near Tivoli: a base with griffins, Corinthian capitals, bench supports, heads of rams and deer, a vase now known as the Boyd vase and a large amount of Egyptian or Egyptianizing artefacts and statues, most famously various Egyptianizing statues of Antinous, Hadrian’s lover. They show many of the forms and ornaments that Piranesi would use, not simply to copy them or to restore them, but to appropriate them and transform them into what he felt could very well have been Roman artefacts. These objects would next return in many Empire designs. In other words, Piranesi did not literally copy or faithfully restore artefacts as he saw them emerging from the Pantanello swamp, but he did follow their manner of composition, with the design overdrive that distinguishes much of his work (Charles-Gaffiot and Lavagne 1999: 43–61, 75–85, 91–99 and 266–372; Spier et al. 2018: 283–93). Many forms would return in his furniture design, such as the lion’s legs with head that reappear, in a slightly more sober form, in the console tables now in Minneapolis and Amsterdam (Figure 12; Ficacci 2011: nr 656).

So what Piranesi presented as genuine Roman works are in fact imaginative transformations, based on his superior knowledge of what we would now call Roman material culture, acquired through many decades of excavations, drawings in situ and etching. His goal was not Vitruvian symmetry and decor, despite his claims to the contrary, but variety, ingenuity, liveliness, lightness and freedom. An art, we might say, of transformation rather than imitation. Piranesi’s plates for the Observations on the Letter of Monsieur Mariette (2002) and Diverse maniere show combinations of motifs and forms that are often difficult to decipher (and the iconography of Piranesi’s etchings is a notoriously underdeveloped field), except that they often thematize metamorphosis and transformation, from the mineral to the vegetal and the animal, from the natural to the supernatural, or from one material to another. It is not accidental that he used a passage from the Metamorphoses by Ovid as an inscription for Plate VII in the Observations: ‘Rerumque novatrix ex aliis alias reddit natura figuras’ (Nothing retains its own form; but Nature, the great renewer, ever makes new shapes out of other forms) (Ovid, Metamorphoses XV.252–3; the quote should actually read ‘Nec species sua cuique manet, rerumque novatrix/ex aliis alias reparat figuras’).

Pompeii and Alexandria

Piranesi’s late work reveals an approach to composition that is very different from the Vitruvian and Academic tradition, which defended unity, simplicity, coherence and perspicuity. As the examples cited in the previous section show, Piranesi sought complex combinations of heterogeneous elements, and ignored the demarcations between genres and styles. Nor did he consider function or decorum as a guiding principle. Instead of symmetry and balance, he aimed for the creation of layers of objects. The resulting objects and images might be described as collages and bricolages, were it not that there is powerful logic at work in them. But to discern that logic, we need to go back even further in time to look for the common ancestor behind Piranesi’s work and the mural painting and decorative art of Herculaneum and Pompei: Hellenistic art and poetry, in particular as developed in the major creative hub of the Hellenistic world, Alexandria (La gloire d’Alexandrie, 1998; Lempereur 1998; Lloyd 2018; Landvatter 2018). Founded by Alexander the Great, Alexandria developed into the economic and cultural centre of the ancient world during the third century BC. From around 200 to 30 BC, Alexandria truly was a world city, a cosmopolis full of people and artefacts from all over the Graeco-Roman world and its trade connections that reached into the Middle East, India, China, the Black Sea region and Africa. With the arrival of an unprecedented variety and abundance of objects, a new objectscape (Versluys 2017) originated that offered a hitherto unparallelled scope of stylistic choice. The resulting new styles were so much more than the ‘hybrid’ sum of their parts that scholars have coined the term Alexandrianism to characterize them (Queyrel 2012; Connelly 2015). These scholars are giving new life to a term that had been first introduced in 18th-century literary history and criticism to define the poetry produced in Alexandria. According to Hellenists like Heyne, this poetry stood out not just for its virtuoso character, but also for being frivolous and decadent, with a preference for learned language and mixing or transforming genres, presenting a silver age after the golden age of the great Attic tragedians and historians (Heyne 1763; Polke 2009; Silk 2004). The term Alexandrianism was reintroduced in the 1880s by the archaeologist Schreiber to refer to a style in Alexandrian and Roman sculpture, mosaics and wall painting, distinguished by the appearance of the grotesque, the picturesque and the idyllic, and by the frequent representation of wild animals, often uniting Oriental, Greek and Egyptian pictorial and iconographic traditions (Schreiber 1885). Whether such a style actually existed, and whether Alexandrianism is the right term for it, remained much debated (Stewart 1996).1 This brief overview of the various meanings attributed to art associated with Alexandria demonstrates that it is always similar to what we would now call eclecticism, but with opulence, sophistication and the ambition to combine the very best examples of the arts of the past.

The statues of the Ptolemaic rulers represented as pharaohs form probably the best-known example of this new way of combining different styles in one artefact, but the architecture of Alexandria also shows this new attitude towards design (Figures 13 and 14; see also Spier et al. 2018, cat. no. 106 and fig. 48). Its influence spread across the Near and Middle East. Now that most monumental architecture in Alexandria itself no longer survives, the more intact monuments of Petra give a very good idea of what has often been called Hellenistic baroque: the use of broken and elliptic pediments; convex and concave fronts; combinations from different orders into one constellation, such as combining an Ionic column with a Corinthian or composite capital, that were unheard of in Greece; the insistent presence of animal forms, often combining Assyrian, Egyptian, Greek and Roman elements into one artefact; and animation, which contemporary sources often commented on. All these elements, as we have seen, are also present in Pompeii and Herculaneum, and in the fragments surviving from Hadrian’s Villa, which was the emperor’s conscious attempt to recreate an Alexandrian complex in Italy, as is shown most clearly in the Canopus and Serapaeum (first noted in Hittorff 1861; see also McKenzie 2007: 100; Curl 2000: 123–48; MacDonald and Pinto 1995: 106–9). Piranesi, like Empire architects and designers such as Percier and Fontaine, was very familiar with these monuments of Hellenistic art and interior design.

As Judith McKenzie has recently argued convincingly, Alexandrian architecture is the most plausible common ancestor for both Pompeian painted and actual Hellenistic baroque architecture in Petra. The surviving mosaic and pictorial records of Alexandrian architecture show the blue backgrounds that we also find in Pompei. Also, the technique of vanishing point perspective, whose use is very conspicuous in Pompeian wall painting of the Second and Third Styles, was developed in Alexandria, perhaps not coincidentally the place where Euclid taught optics in the early 3rd century BC (McKenzie 2007: 100–108). The wall paintings in Room 23 of the Villa of Oplontis near present-day Sorrento, for instance, probably built for Nero and his wife Poppaea, and rediscovered in the 18th century, show clear similarities with the façade of tomb 8 in the Moustapha Pasha Tomb in Alexandria, but also with the façade of the Deir tomb in Petra: they all have the same distinctive articulation of a pedimented façade in two flanking elements, connected by an entablature, surrounding a central bay with a segmented or concave pediment. They also all share the combination of Doric friezes with Corinthian capitals (McKenzie 1990: plates 223–44).

In the Hôtel de Beauharnais, as in many other Empire interiors, similar features return. The illusionistic wall paintings of the four seasons, for instance, recall the wall paintings at Herculaneum of dancers against dark monochrome backgrounds. The combinations of motifs in gilt mouldings integrate elements from different orders and cultures in the same way as in Petra, with griffins, eagles, palmettes and acanthus leaves. A very frequent feature in many of Percier’s designs is the grotesque figure of a naked torso emerging from acanthus leaves, which is also documented in Petra (Le Pitture d’Ercolaneo 1757, vol. 1: plates XIX and XX; XL–XLIII; McKenzie 1990: plates 110b, c, 111a, 112, 119, 178, 138).2

Underlying this richness and variety of forms and styles is an approach to design that is fundamentally different from that developed in the Vitruvian tradition, with its stress on formal consistency (without combinations from various orders), decorum and adherence to tradition. If we employ the distinction between design concepts and formal languages, developed in recent studies of 19th-century architectural eclecticism, we can more fully understand the innovative character of Alexandrianism (Van der Woud 2002: 3–25). Design concepts are approaches to how artefacts, art works or buildings are put together: by means of bricolage, adding one part after another as they become available, or by the thorough planning based on a pre-existing intellectual concept of the whole that is the basis of Renaissance theories of disegno. The Beaux-Arts distinction between parti and marche is a design concept as well. But such concepts can be applied to different formal languages or styles: the Houses of Parliament in London, for instance, combine a late Tudor repertoire of forms with a Beaux-Arts parti. This dissociation of design concept and formal language occurs for the first time, I would argue, in Hellenistic cities such as Alexandria from around 200 BC onwards. It is exemplified in Hellenistic poetry, with its hitherto unseen stylistic variety, but also in the interior design style of the Third Pompeian style. Between 1450 and 1750 this dissociation was obscured by the merging of design concepts and formal language in the revival of classical art and architecture, but the discovery of Herculaneum and Pompeii sparked its re-emergence in Piranesi’s polemic against Vitruvian design concepts. His examples of such a style in the Diverse maniere, with their accumulation of forms and styles from very different periods and regions and their apparent lack of premeditated formal organization, are a visual polemic against the Renaissance design concept of disegno and its 18th-century French descendants of convenance and bienséance.

This stylistic variety, which was once called eclecticism or hybridity, or ‘Hellenistic baroque’, was already associated with Alexandria in antiquity (Payne 2008). Conspicuous examples are the varying styles used for royal portraits: Ptolemy I is for instance depicted both in marble, with the face of a Hellenistic ruler, and in basalt, as an Egyptian Pharaoh (Figures 15 and 16). Accounts of the magnificent floating pavilion decorated with hundreds of marble animals created for Ptolemy II Philadelphus (reigned 285–246 BCE) by Athenaeus, or the reception of Antony and Cleopatra by Plutarch, all evoke the overwhelming luxury, defiance of structural logic, stylistic range and sheer excess of these often ephemeral structures. In the fifteenth Idyll by Theocritus, visitors to a religious festival in Alexandria are overwhelmed by this opulence, but also by the vividness and suggestion of animation of the statues they have come to admire (Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 5.194–206; Plutarch, Life of Antony, 46; see also Thompson 2000).

Alexandrianism as a critical concept was introduced in late 18th-century literary history to refer to the perceived decline in originality and the preciousness and over-refinement of the poetry produced in Alexandria during the Hellenistic period by poets such as Callimachus, who parodied, reversed, transformed, quoted and copied the great epic poets. The term came to be applied to late-Republican and Augustan poets such as Catullus, Ovid and Vergil to define their extremely sophisticated appropriations and transformations of Greek models, from Homer and Hesiod to the great tragic poets (Hölscher 2004; Elsner 1998: 169–86; Versluys 2016). The designs of Percier and Fontaine in their publication of Roman palazzi very much recall the sophisticated, overly rich compositional bricolage and chronological layeredness we also find in Alexandrian poetry, or in Pompeian art of the Second and Third Styles, for that matter.

An important feature of such Alexandrianism, both in poetry and the visual arts or architecture, is its intense awareness of the past, of the historically constituted position of the artist. Alexandrianist art is an art determined by a poetics of appropriating, recreating and transforming the past, preferably by showing how layers of the past can be imposed on each other. Perhaps the most telling example in poetry is Vergil’s Aeneid, whose story is a transformation of the Odyssey, like his main hero, as well as a reversal of the main theme of the Iliad, that of the destruction of a city and nation. It is also a very conscious statement about the historical relation between the past (Greece) and the Imperial present (Rome). This poetics was probably nourished by the particular political situation in both Egypt and Alexandria: one of succeeding regimes that begin by trying to impose themselves on the existing culture, but all, sooner rather than later, end up assimilating, and taking over, the main characteristics of Egypt. A typical feature of such a successor state as Alexander’s empire is to inscribe itself in the tradition of the countries he conquered. Piranesi devoted his entire life to a material and visual recreation of the Roman past in the present, and Napoleon’s artistic policy was to a large degree aimed at recreating the material presence of Imperial Rome in Paris, and thereby making him the legitimate successor to Augustus.

Conclusion

Both the concept of composition and that of style, in the sense of a distinction between form and content, between what you say, do or make and how you do it, are rhetorical inventions (Baxandall 1971: 121–40; Puttfarken 2000: 3–45, 263– 79). They were codified in Cicero’s De Oratore. Quintilian was the first to apply this rhetorical concept to the visual arts in a systematical way, when in Book XII of the Institutio oratoria he developed a stylistic analysis of the various schools of sculptors. He did so from an awareness that there is a classical norm and there are deviations from it; but also from the awareness that the classical is always something in the past, and mainly a desirable past (Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria II.xiii.8–11 and XII.x.1–12; see also Van Eck 2006: 139–41). It is this very awareness that also drove the integration of various styles that form the Empire style, just as that awareness had done in Piranesi’s work. His compositional method is not aimed at restoring antiquities. Instead, he placed himself in the tradition of Roman art and design, aiming for the utmost virtuosity and formal lavishness, variety and opulence.

The second defining feature of the Empire style is a very Alexandrian awareness of the layeredness of the past, which resulted in a very consistent attempt to materially recreate it by making artefacts that somehow, in their formal richness and closeness to Roman precedents, would express that sense of layered continuity and perseverance. In his one built church, Santa Maria del Priorato, Piranesi comes very close to a built statement of this Alexandrian design concept, for instance in the reed sarcophagus motif surrounding the oculus, one of the few surviving elements from the previous, mediaeval fabric, and his version of the snake/egg-and-dart motif that reveals its own etiology (Figure 17). Such a layered, self-conscious integration of the past into the present, and of different cultures into a new whole, is typical of Alexandrianism in both literature and the arts.

The Hôtel de Beauharnais displays many of the characteristics defined here. There is a similar distinction between design concept and formal language. While the original, early 18th-century spatial lay-out of a hôtel particulier is largely kept intact, its appearance is completely transformed by its glittering new dressing, in which the most evocative and magnificent examples of Egyptian and Roman art are recreated through the lens of Piranesi’s transformation of Pantanello fragments. Its formal language is not that of the Roman Empire or of Egypt alone, but a new composition of all these elements based on the models of Pompei and Alexandria.

Notes

- See also Connelly (2015: 174ff) for an overview of the main contemporary sources that support the idea of an Alexandrian style conceived in the Hellenistic period, in particular the description by Athenaeus of the festival pavilion of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. [^]

- The features in McKenzie (1990) include griffins and eagles (plates 110b, c); torso and acanthus leaves (111a); Doric frieze with Ionic cornice (112); Corinthian tomb with half pediment and Doric frieze (119); reconstruction of the Moustapha Pasha Tomb, chamber 1, showing a combination of sphinxes, Doric columns flanking a square new variety of capitals and frieze (178); and a tomb façade at Deir near Petra, very similar to the architecture depicted in the Villa at Oplontis (138). [^]

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Baxandall, M. 1971. Giotto and the Orators: Humanist Observers and the Discovery of Pictorial Composition. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Bignamini, I and Hornsby, C. 2010. Digging and Dealing in Eighteenth-Century Rome, 2. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Blondel, J-F. 1752–56. Architecture Française. Paris: Charles-Antoine Jombert.

Boffrand, G. 2002. Book of Architecture, van Eck, C (ed.). Trans. by David Britt. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Brice, G. 1725. Nouvelle Description de Paris. Paris: T. Le Gras.

Brice, G. 1752. Description de la ville de Paris, et de tout ce qu’elle contient de plus remarquable. Paris: Chez les libraires associés.

Charles-Gaffiot, J and Lavagne, H. (Eds.) 1999. Hadrien. Trésors d’une villa impériale. Exhibition catalogue. Paris: Mairie du Ve Arrondissement.

Connelly, B. 2015. Alexandrianism: A 21st Century Perspective. In: Leriche, P (Eds.), Art et civilisations de l’Orient hellénisé. Rencontres et échanges culturels d’Alexandre aux Sassanides, 173–182. Paris: Picard.

Curl, JS. 2000. Egypt in Rome — An Introductory Essay. Part Two: The Villa Adriana and the Beginnings of Egyptology. Interdisciplinary Science Review, 25: 123–48. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1179/030801800679143

Dansette, A. 1969. Napoléon, Pensées politiques et sociales. Paris: Flammarion.

‘Du haut de ses pyramides …’. 2013–14. L’Expédition d’Egypte et la naissance de l’égyptologie (1798–1850). Exhibition catalogue. La Roche-sur-Yon: Musée de La Roche-sur-Yon.

Ebeling, J and Leben, U. (Eds.) 2016. Le style empire. L’hôtel de Beauharnais à Paris. Paris: Flammarion.

Elsner, J. 1998. Imperial Rome and Christian Triumph. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Ficacci, L. 2011. Giovanni Battista Piranesi. The Complete Etchings. Cologne: Taschen Verlag.

Frommel, S, et al. (eds.) 2014. Charles Percier e Pierre Fontaine, dal soggiorno romano alla trasformazione di Parigi. Rome: Silvana editoriale/Bibliotheca Hertziana.

Gaehtgens, T, Ebeling, J and Leben, U. 2007–8. Eugène de Beauharnais: Honneur et Fidélité at the Hôtel de Beauharnais. In: Nouvel, O (Eds.), L’aigle et le papillon: Symboles des pouvoirs sous Napoléon, 1800–1815. Exhibition catalogue. Paris: Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

Garric, J-P. (Eds.) 2017. Charles Percier. Architecture and Design in an Age of Revolutions. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Hammer, K. 1983. Hôtel de Beauharnais à Paris. Munich and Zurich: Artemis.

Heyne, CG. 1763. De genio saeculi Ptolemaeorum. Göttingen.

Hittorff, J. 1861. Pompei et Petra. Revue Archéologique, 6: 1–18.

Hölscher, T. 2004. The Language of Images in Roman Art. Trans. by A. Snodgrass and A. Künzl-Snodgrass. Cambridge and New York: University of Cambridge Press.

Hubert, E. 1972. Les mystères de l’Egypte avant Champollion. Archéologia, 52: 46–53.

Humbert, J-M. (Eds.) 2009. Bonaparte et l’Egypte. Feu et lumières. Exhibition catalogue. Paris: Hazan.

Hyde Minor, H. 2015. Piranesi’s Lost Words. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

La gloire d’Alexandrie. 1998. Exhibition catalogue. Paris: Petit-Palais.

Landvatter, T. 2018. Contact Points: Alexandria, a Hellenistic Capital in Egypt. In: Spier, J, Potts, T and Cole, E (Eds.), Beyond the Nile. Egypt and the Classical World, 128–35. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Lempereur, J-Y. 1998. Alexandria Rediscovered. London: British Museum Press.

Le Pitture antiche d’ercolaneo e contorni. 1757. Naples: Stamperia Regia.

Lloyd, AB. 2018. The Coming of Alexander and Egypt under Ptolemaic Rule. In: Spier, J, Potts, T and Cole, E (Eds.), Beyond the Nile. Egypt and the Classical World, 119–28. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum.

MacDonald, WL and Pinto, JA. 1995. Hadrian’s Villa and its Legacy. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

McKenzie, J. 1990. The Architecture of Petra. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

McKenzie, J. 2007. The Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt c. 300 BC–700 AD. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Panza, P. 2017. Museo Piranesi. Geneva and Milan: Skira.

Payne, A. 2008. Portable Ruins: The Pergamon Altar, Heinrich Wölfflin and German Art History at the fin de siècle. RES. Journal of Aesthetics and Anthropology, 54/55: 168–89. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1086/RESvn1ms25608816

Penny, N. 1992. Catalogue of the Sculpture in the Ashmolean Museum. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pillepich, A. 1999–2000. Eugène de Beauharnais. Honneur et fidélité. Exhibition catalogue. Malmaison: Musée National de Malmaison.

Piranesi, GB. 1756. Antichità romane. Rome: Bouchard and Gravier.

Piranesi, GB. 1769. Diverse Maniere di Adornare i Cammini … con Ragionamento apologetico in diffesa dell’architettura egizia, e toscana. Rome: Generoso Salomoni.

Piranesi, GB. 2002. Observations on the Letter of Monsieur Mariette with Opinions on Architecture. Trans. Caroline Beamish and David Britt. Los Angeles: The Getty Centre.

Polke, I. 2009. Selbstreflexion im Spiegel des Anderen. Eine Wirkungsgeschichtliche Studie zum Hellenismusbild Heynes und Herders. Würzburg: Königshausen und Neumann.

Pons, B. 1989. L’Hôtel Beauharnais. Monuments historiques, 166: 89–104.

Puttfarken, T. 2000. The Discovery of Pictorial Composition: Theories of Visual Order in Painting 1400–1800. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Queyrel, F. 2012. Alexandrinisme et art alexandrin: nouvelles approches. In: Ballet, P (Eds.), Grecs et Romeins en Égypte. Territoires, espace de la vie et de la mort, objets de prestige et du quotidien, 235–256. Cairo: IFAO.

Raoul-Rochette, D. 1840. Percier: sa vie et ses ouvrages. Revue des deux mondes, 4(24): 246–68.

Samoyault, J-P. 2009. Mobilier français Consulat et Empire. Paris: Gourcuff et Gradenigo.

Sawicki, D. 1999. Die Gespenster und ihr Ancien Régime. Geisterglauben als ‘Nachtseite’ der Spätaufklärung. In: Neugebauer-Wölk, M (ed.), Aufklärung und Esoterik. Hamburg: Meiner Verlag.

Schreiber, T. 1885. Alexandrinische Skulpturen in Athen. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, 10: 385–400.

Silk, M. 2004. Alexandrian Poetry from Callimachus to Eliot. In: Hirst, A and Hirst, M (Eds.), Alexandrianism, Real and Imagined. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Spier, J, Potts, T and Cole, E. 2018. Beyond the Nile. Egypt and the Classical World. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Stewart, P. 1996. The Alexandrian Style: A Mirage? In: Hamma, K (ed.), Alexandria and Alexandrianism, 231–47. Santa Monica: The Getty Institute.

Thompson, DJ. 2000. Philadelphos’ Procession: Dynastic Power in a Mediterranean Context. In: Mooren, L (ed.), Politics, Administration and Society in the Hellenistic and Roman World. Louvain: Peeters.

Van der Woud, A. 2002. The Art of Building: From Classicism to Modernity. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Van Eck, CA. 2006. Classical Rhetoric and the Visual Arts in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Van Eck, CA and Versluys, MJ. 2017. The Hôtel de Beauharnais in Paris: Egypt, Rome, and the Dynamics of Cultural Transformation. In: Von Stackelberg, K and Macaulay-Lewis, E (Eds.), Housing the New Romans, 54–92. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Versluys, MJ. 2016. Visual style and Constructing Identity in the Hellenistic World. Nemrud Da? and Commagene under Antiochos I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Versluys, MJ. 2017. Object-scapes. Towards a Material Constitution of Romanness?. In: Van Oyen, A and Pitts, M (Eds.), Materialising Roman Histories, 191–99. Oxford: Oxbow. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1v2xtgh.18

Warner, M. 2006. Phantasmagoria: Spirit Visions, Metaphors and Media into the Twenty-First Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.