Berlin’s Palace

Brigitte Sölch

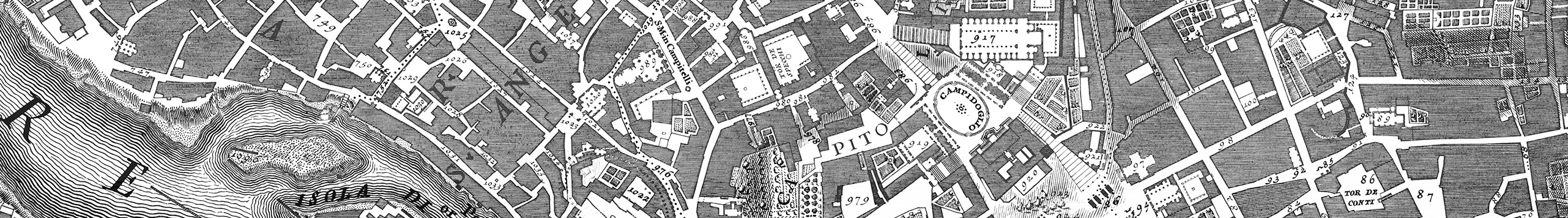

The work is not new but it appears for a second time: Berlin’s Palace, currently only visible from the outside (Figure 1). This monumental (neo)baroque complex has not risen from ruins. It has been rebuilt to the delight of its advocates who speak about the necessity of healing an open wound in the city, to the anger and disappointment of its critics, who still rub their eyes and wonder how all this could happen. How did it come about that Berlin’s Castle — damaged during World War II, blown up in 1950 by the East German leader Walter Ulbricht, replaced in 1974 by the multifunctional modernist building for cultural events and sessions of the East German Parliament — was rebuilt as Berlin’s ‘new historic center’ after the Palace of the Republic was torn down, step by step, beginning in 2006? The whole process provoked such an extensive and controversial debate since its beginnings in the early 1990s that it’s not possible to go into detail here. The hotly debated Humboldt Forum, whose gradual opening as a museum for ‘non-European’ cultures will begin by the end of 2021, launched a new website for ongoing information and controversial discussions in both German and English.

Even from the very beginning, images played an essential and suggestive role in this process. The private businessman Wilhelm von Boddien (from Hamburg), founder of the association for the reconstruction for which he’s still responsible, began a professional campaign together with the architectural historian Goerd Peschken and the architect Frank Augustin. As the art and architecture historian Adrian von Buttlar writes in his essay ‘Berlin’s Castle Versus Palace: A Proper Past for Germany’s Future?’:

Backed by a growing number of the conservative intellectuals and politicians, the idea struck public opinion when Boddien in 1993 realized an extraordinary illusory effect by a painted 1:1-simulation of the Castle, partly reflected and elongated by a mirror on the Palace facade. The mock-up was accompanied by a simultaneous exhibition documenting the forgotten building and explaining the alleged necessity of its resurrection. (Future Anterior, 4(1) (2007): 22)

Neither a new building nor the integration of parts of the Palace of the Republic had a chance after the first official competition for the inner city of Berlin in 1992–93.

At first glance, the palace looks artificially smooth, without any traces of age. However, since preserved fragments were reused and the reconstructed details of the decoration are in fact of high quality craftsmanship, the architectural surface gains a certain liveliness upon closer inspection. The partial reconstruction thus may become a life-sized model, so to speak, for the discussion and examination of historical reconstruction questions.

In an unintended irony, the palace simulacrum appears like an architecture of fusion, as if the three baroque facades were the result of a historic building reconstructed on the basis of some remains, supplemented on the east side by a totally new, unornamented, and brilliant white façade. The architectural language of this fourth facade is characterized by a geometrical order and paratactic rhythmic play of the rectangular windows. Without the inscription ‘Humboldt Forum’ as an integral part of this three-story façade oriented toward eastern Berlin, one would have no idea of the function of the building. Some describe this grid façade as fascist-like architecture, others as a manhole cover, and yet others consider it the only interesting part of the building. Its author, the architect Franco Stella, from Vicenza, Italy, along with two other offices, was responsible for this reconstruction, called the Franco Stella Humboldt-Forum Projektgemeinschaft, since the competition 2008.

Confronted with the emerging abundance of Prussian-monarchic decorum in Berlin’s ‘new historic center’, one may actually experience a certain relief in front of the grid façade, which is connected to the Spree River by two diagonal ramps. On the one hand, one feels reminded of Aldo Rossi’s architectural concept of ‘type’ and his thoughts about the city as ‘locus di memoria’. On the other hand, one also recognizes exactly the opposite. The eastern façade does not evoke any allusion to the former fusion character of the east side of Berlin’s palace, which was continually extended and rebuilt over 500 years. In the 18th century, Andreas Schlüter had incorporated significant medieval and Renaissance parts of the castle into his new baroque building. Johann Friedrich Eosander then doubled the size of the palace in the direction of Unter den Linden before Friedrich August Stüler was entrusted with the construction of the immense dome above the portal in the middle of the 19th century, after the view from the west had been established. But over the centuries, the history of the palace remained clearly visible in the east and was quite often portrayed in a picturesque manner.

Representative architectures like Berlin’s Palace will always make present what remains absent: the non-reconstructed parts, the demolished buildings, the lost ‘originals’, the alternative concepts shown in the competitions, all the many published and unpublished discourses, images, and layers of history. From this perspective, it becomes clear that architecture is to some extent also unstable and processual. This applies even now to the partial reconstruction. There is talk of reconstructing the dome in a manner true to the original while adding a (much less visible) inscription to it in honour of the donor, Werner A. Otto, produced by his wife, Inga Maren Otto. Furthermore, there is talk of erecting a widely visible structure on the roof for the future restaurant, next to the dome, with a fantastic view over Berlin as its selling point.

Keeping in mind the potential changeability of architecture, one could also hope that the seemingly ‘original’ exterior of the building will be broken up by further transformations and additions in the future. But that’s only one side of the coin. For those who try to raise funds for the reconstruction, such as Wilhelm von Boddien’s association, process means something completely different: namely, the extension of the historic reconstruction into the urban environment.

From the very beginning, image production and castle reconstruction have been closely connected and thus require some critical analysis. First came the graphic mock-up of the building, then the partial reconstruction based on historic pictures. At the time of writing, it is — aside from the construction site — the material shown first in the temporary exhibition space, called Humboldt Box, and now in the Schloss Center, which informs the public about the project and with which Boddien’s association is trying to raise funds for the ongoing reconstruction of the architectural decoration. The presentation includes a video that not only shows the renderings of the partially reconstructed palace but also the desired future reconstruction of its urban environment. Instead of the planned Berlin Monument to Freedom and Unity, Germany (by Sasha Waltz and Milla & Partner, designed 2011), the west side is shown with the reconstructed colonnade of the neobaroque Kaiser Wihelm I Memorial, a project that had been seriously discussed in 2017, yet again, in the Bundestag and turned down. Even more: The urban space around the castle is dedicated to both pedestrians and Reinhold Begas’ neobaroque Neptune Fountain and its monumental horse tamers slated to be reinstalled around the palace.

Of course, democratic negotiation processes could result in at least one transfer of monuments. But this requires a broad and critical discussion of the material from historic and contemporary perspectives. Such a democratically negotiated decision could then also result in moving a monument back to its original location and possibly commenting on it with a counter-monument. Focusing on the ‘beauty’ or ‘historical identity’ of a place that has long since passed through a different history is not enough. There is no void as such in a place where so many histories and urban transformations took place and where the social, cultural, and political public sphere needs to be debated, along with the visibility and dimension of shared histories.

The aforementioned video projection, meant to win donors for the reconstruction, actually shows the castle surrounded by historic monuments but without conveying the greater appearance of its urban environment. The surroundings consist of abstract volumes, with a few exceptions, such as the cathedral, whose golden cross on top of the dome is never shown, quite in contrast to the palace, on whose dome was fixed, in 2020, the controversial motif of the golden cross, rising above Eosander’s Portal on the west side.

The original palace’s dome and its lantern had been criticized even in the late 19th century for being an inelegant architectural solution above the triumphal portal. Furthermore, the whole political-religious symbolism of the dome with cross and inscription, commissioned by Friedrich Wilhelm IV in 1845, can hardly be understood without the former chapel below, which has not been reconstructed. However, restoration advocates have repeatedly argued that it is all about the historicity of the external appearance and urbanistic effect. Of course, many historic buildings have retained their outer appearance while their inner structures and functions changed. But once a decision is made to rebuild a structure that no longer exists, such elements have to be discussed differently. Moreover, this type of a dome, with a golden cross over a chapel, crowning the palace, remains unusual even for the mid 19th century — a time when nation states began to upgrade their political institutions with large domes as secular political signs.

Berlin’s palace is, of course, still rich in secular political messages. The Eosander Portal, for example, is an interpretation of ancient Roman triumphal arches (Septimius Severus). In the 17th and 18th centuries, such triumphal portals, effective motifs both architecturally and urbanistically, gained further importance as symbolic expressions of military and monarchical power, supporting expanding territorial claims to power. It is not without reason that the reconstructed inscription above the portal states that the castle was founded during the times of war by Friedrich II and is worthy of a warlord. In the future, visitors to the Humboldt Forum will pass through this portal.

Architecture is neither guilty nor innocent. Strong historic images can become weak but can also regain new strength. This makes it all the more crucial to keep in mind that seeing and thinking are not separable. This is crucial, since the reconstruction of Berlin’s Palace is accompanied by narratives and images that will also require critical examination in the future.

Kulturforum Berlin

Elke Nagel

The modern architecture of Berlin’s Kulturforum is a veritable stacking of icons, including the Neue Nationalgalerie, Philharmonie, Kammermusiksaal and Staatsbibliothek (Figure 2). The main flank of the square is dominated by the flat museum complex, divided into cubic volumes, housing the Kunstgewerbemuseum, the Kupferstichsammlung, the Kunstbibliothek and Gemäldegalerie.

View of the Kulturforum, main plaza Berlin, 2018. Photo: Membeth, Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kulturforum.Berlin.Portal.jpg.

Thus, the viewer’s perception of the Kulturforum is restricted by the fact that it is a topographically undefined urban quarter between the Landwehr Canal and Tiergarten, which means that, thanks to the historical territorial upheavals of the 20th century, the area must be understood as West Berlin’s outermost edge and later the center of the reunited capital. Unlike the Museum Island, the buildings are not united by a common urban space, but are rather each individually formed by their own focal points at opposite ends of a large central open space.

To understand the dilemma of the site, it is necessary to take a look at some of the stages of its construction history. For the first time, in 1938, large parts of a villa quarter had to give way to the eradication of the ideologizing Götterdämmerung of the Nazi capital, offering space for a center of German tourism. Later, the destruction of war did its part. Political revision only a few years after the lost war washed away all that remained of the pre-war buildings in the course of the rubble-clearing — sham liberation. The urban caesura of the construction of the Wall manifested the new symbolic character of the place. The Philharmonie was the first sign of life on this square plagued by melancholy. Several iconic cultural buildings were grouped in loose succession around St. Matthäus Church, the only survivor of the 19th-century settlement, and were intended to form an opposing counterweight to the Museumsinsel, now in East Berlin. These included the Philharmonie (Scharoun, 1963), Neue Nationalgalerie (Mies van der Rohe, 1968), Staatsbibliothek (Scharoun, 1978), Kunstgewerbemuseum (Gutbrod, 1985), Kammermusiksaal (Scharoun/Wiesniewski, 1987) and Gemäldegalerie (Hilmer/Sattler, 1998).

In Hans Scharoun’s Philharmonie building, which was completed in 1963, the sculptural form of the structure shines in a golden hue, its outer skin seemingly stretched over the organic volumes created from its musical function. The façade consists of jointed panels whose structure brings the building to life in a play of light. The staged sequence of rooms inside, which culminates in the large concert hall, can also be seen in the outer form. Above a flat structure rises the dynamic peak of the ‘cathedral of culture’, demonstrating the spirit of its construction period, a future-oriented belief in progress.

In the second cultural building, the Neue Nationalgalerie (1968), the radical clarity of design of the architect, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, is evident. In the firm conviction that building and construction are inseparable, he created a universal, panoramic building. The gigantic self-supporting plate of steel is buttressed by tapering columns. The prominent location at the southern end of the square has little effect on the square design due to the undirected nature of the building and its functional introversion. Recently, the exhibition space has been expanded by a complex reconstruction of the base floor, without taking away the design sharpness of the original building.

For the first time, the Staatsbibliothek had a space-creating effect, since Scharoun’s 1978 design included a plan for the quarter’s outdoor space. Scharoun reacted to the division of the city with a mountain of books. It is often stated that a special attraction of the building is that negatives are subtended into spatial qualities: the busy street disappears behind the magazine. Analogous to the Philharmonie, the interior shapes the cubature: the elongated building site is translated as the path of the book, and reading room areas become balconies and terraces. Scharoun mediates with the quotation of the façade material, but on an overall cubic form, between the fragmentation of the music house and the tectonic horizontal structure of Mies van der Rohe’s Nationalgalerie. At the same time, he sets an unmistakable sign for the forum, which, after being closed on three sides, is now clearly oriented toward the west.

The large museum, from the pen of Rolf Gutbrod, of which until 1985 only the first section was realized, with the Kunstgewerbemuseum, the Kupferstichsammlung and the Kunstbibliothek, closes the fourth side of the square. Gutbrod’s propaedeutic approach to building culture did not meet the taste of his contemporaries. His fine material aesthetics and the translation of multiple functional demands into a fractured form of almost naive monumentality were not appreciated. The second phase of construction, including the Gemäldegalerie, foyer, and connecting building, was undertaken by the Munich-based firm of Hilmer und Sattler (1998), which strove for formal unity but realized a far more restrained design. The conglomerate is the only museum in the Kulturforum that directly borders the square and turns its full attention to it.

The Kammermusiksaal, which was planned after Scharoun’s death by his close colleague Edgar Wiesniewski in 1987, fits into the ensemble on the east side of the square, despite its oversized volume. Colour, cubature, and height graduation subtly mediate between Scharoun’s solitaires, closing the construction line. Due to the wide road space of the Potsdamer Straße, this side of the square remains unclosed. The claim resulting from the name ‘Forum’ could not be satisfied even after decades of construction.

The sum of the solitary buildings, each of them of significant but not undisputed architectural value, certainly validate the ‘culture’ part of the forum’s name, but they do not articulate the togetherness of a forum. The forum idea was not formed until the late 1960s and into the 1970s, originating from Scharoun’s planning for the area surrounding the Staatsbibliothek, which negated any east–west connection by radically overbuilding the old Potsdamer Strasse. Scharoun’s cityscape was dominated by anti-urban open space and the dynamics of the car culture of the new West Berlin.

The retention of the segregating planning concept, which was no longer regarded as a universal urban planning ideal since the ninth and tenth CIAM congresses, caused paralyzing discussions for decades. The development of the large square next to the church with a guest house was intended to create moderate urbanity. The constant fear of large squares reminiscent of authoritarian power structures led to an urban planning ideas competition, which from 1972 onward sought a form of integration for the large-scale project along the Spree. This effort, like the replanning of the so-called ‘Zentrum des geteilten Berlin’, in each case involving renowned architects, was as unsuccessful as it was lacking any significant consequences. In 1984, in the course of a political paradigm shift, an international process favoured a design by Hans Hollein, whose reversal of the urban planning effect could not be greater. Colonnades, a tower, and a square converted the exterior space into interior space, reducing any pedestrian traffic rather than creating a space with any vitality. Initially received with benevolent support from politicians, there was soon such massive resistance from within the professional world that the discussion came to a complete standstill. In 1987, the German architectural magazine Baumeister resumed the enduring dispute:

The critical area of development is naturally near the Wall, and has remained in planning limbo for three decades. A cultural center has gradually arisen since the fifties, and master plans for the general development have been created: Scharoun presented his in 1964. His design was suddenly replaced in 1983 by Hans Hollein’s controversial master plan – a decorative concept which has subsequently been discussed, criticized and repeatedly postponed. All questions are still unsettled at the moment. (Baumeister 6 (1987): 33)

German reunification once again turned the urban location upside down. The Kulturforum was suddenly no longer merely a symbolically central theme; the neighboring Potsdamer Platz, with its rapidly growing urban crown, literally eclipsed the buildings of the Kulturforum. The wasteland between the singular individual structures, dominated by their formal components, posed a challenge to the revitalization of the square. Because most of the main attractions faced their entrances away from the piazzetta, as the ramp-like sloping square in front of the museums was wistfully conceived, the forum remained lifeless. In 1998 the horticultural project aiming at an open center failed in its claim to be a public place of contemplation, hindered by its location partly next to an urban freeway. In 2004–2005, a discussion that is important for today’s development generated interest in the site among a broad professional public and identified the public demand for a return to a mixture of functions, a conglomerate order as a structural principle interlocking enclosed and free space.

Numerous architectural paths of re-urbanization played out. However, the lack of results in the endless planning decisions recently opened up a new chapter in the history of the failure of urban planning. In 2012, the city sought to counteract a decline in visitors and abandon the overall plan in favour of a rapid expansion of the National Gallery. In 2016, these subordinate additions to the existing buildings completely suppressed the space’s significance as a square, reducing it to a gap between buildings. The blank will now be filled. With the allocation of the competition prize for the Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts to the oversized, formalized gabled-roof house designed by the partnership of Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron on the previously large open space, all of Scharoun’s and Hollein’s forum ideas have become superfluous in equal measure.

Your Flight Has Been Delayed

Max Hirsh

Among their European neighbors, German engineers are thought to be an efficient, parsimonious, law-abiding, and unfailingly detail-oriented lot. The 30-year saga of Berlin-Brandenburg Airport (BER) (Figure 3) — with its primary plot points of mismanagement, serial building code violations, and stratospheric cost overruns — flies in the face of those Teutonic stereotypes. What went wrong?

Exterior view of Berlin Brandenburg Terminal 1, 2020. Photo: Arne Müseler, arne-mueseler.com. CC-BY-SA-3.0. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.de.

BER’s woes can be traced back to the heady days after the fall of the Berlin Wall. As the realization set in that Berlin would once again become the capital of a united Germany, transport planners floated the idea of turning the city into the Luftkreuz Europas: an air hub not just for a reunited country, but for a reunited continent. Overcoming Berlin’s fragmented aviation infrastructure — which remained divided between Tegel and Tempelhof airports in West Berlin and Schönefeld in the East — represented the first step toward realizing that vision. In January 1990, the East German transport minister, Heinrich Scholz, proposed the construction of a new airport whose physical scale and cutting-edge design would testify to Berlin’s incipient role as the capital of Europe. Like any good socialist Funktionär, Scholz envisioned two five-year plans: one for master planning and another for construction. By the year 2000, Berlin would wow its visitors with an awe-inspiring megahub, rivaling the likes of Heathrow, Charles de Gaulle, and O’Hare.

The planning for BER began soon thereafter, culminating in 1996 with the selection of a site in Brandenburg, the flat, sparsely populated province surrounding Berlin. As a teenage transport nerd, I absorbed every news item that I could find about the new airport. Would it be connected to Germany’s high-speed rail system? Would it become the new hub for Lufthansa, the national airline? And would the airport be ready in time for the 2000 Olympic Games, which local politicians were keen on bringing to Berlin?

None of those things came to pass. As crucial decisions about the airport were repeatedly delayed, it became clear that BER faced many challenges. In a city that remained physically and culturally divided into two distinct halves, local politics played a big role. From the get-go, BER’s advocates pushed to close Tegel. From a planning perspective, that made sense: borne of Cold War necessity during the 1948 Berlin Airlift, Tegel is adjacent to some of West Berlin’s most densely populated neighborhoods. Thousands of people live under its flight paths. Removing the airport would improve their quality of life and open up new areas for redevelopment. Yet Tegel also holds a special position in the heart of anyone who grew up in West Berlin. In a city surrounded by barbed wire, the airport was the gateway to the world: an emblem of Berliners’ determination to remain connected to the free-wheeling culture and material abundance of the West, despite their isolation behind the Iron Curtain. More than three decades after the fall of the Wall, Tegel remains a powerful symbol of West Berlin culture, and an aesthetic time capsule that evokes considerable emotional attachment.

Designed between 1965 and 1975 by the architects Meinhard von Gerkan and Volkwin Marg (GMP), the airport narrates the transition from modernism to postmodernism, juxtaposing the functional ambitions of the former with the tone-deaf playfulness of the latter. Tegel’s iconic hexagonal terminal was designed around the needs of the car: the terminal’s forecourt is lined with a narrow strip of parking spaces, allowing passengers to literally drive to their departure gate and proceed directly to the airbridges extending from the hexagon’s exterior. That concept proved to be short-lived: as air travel became a mass-market phenomenon, Tegel struggled to cope with the attendant increase in passengers. Yet what GMP lacked in terms of an operational vision of future aviation needs, they compensated for by ushering West Berliners into the aesthetics of postmodernism, extricating the walled city from the geometric rigidity and restrained palette of mid-century modernism. Gigantic numbers and technicolor arrows line the walls of the terminal’s approach road, as if a children’s book illustrator had been tasked with designing its wayfinding system. The terminal’s hexagonal structure is echoed in six-sided motifs throughout the airport: hexagonal wall and floor tiles, hexagonal insulation panels, even hexagonal seating arrangements, all executed in the preferred color scheme (ochre, orange, olive) of the 1970s Bundesrepublik.

Despite Tegel’s limitations, many Berliners rejected BER, at times championing scrappy Tegel’s ability to persevere even as its infrastructure became hopelessly dated. Their lack of enthusiasm trickled up to elected officials, contributing to a distinct lack of momentum surrounding the new airport. That torpor was exacerbated by rivalries between three parochial elites, each of whom had a vested interest — or rather disinterest — in BER: one in Berlin; another in Potsdam, the capital of Brandenburg; and yet another in Bonn, the former seat of West Germany’s government. Although Bonn’s influence has waned since reunification, its armada of civil servants still controls the federal purse strings. Moreover, the West German political class — which flew in and out of Tegel every week — strongly favored the existing airport, just a short taxi ride away from the government quarter. For politicians, the prospect of trekking out to Brandenburg did not exactly spark joy. Nor did BER win the affection of Brandenburgers who, since time immemorial, have kept their weird big-city neighbors at a generous arm’s length. While some welcomed the prospect of job opportunities, many feared an increase in congestion and pollution and — perhaps most threateningly of all — an influx of Berliners.

None of these ingredients proved to be those of a recipe for success. By the early 2000s, Berlin had been redeveloped beyond recognition: the Wall was gone, and what appeared to be the entire population of Swabia was busy remodeling thousands of flats in formerly working-class neighborhoods. By contrast, Berlin’s aviation infrastructure had barely changed. Schönefeld still served budget travelers en route to Mallorca and Anatolia. Tempelhof still felt impossibly oversized, accommodating a handful of flights inside the cavernous brainchild of Albert Speer. And poor Tegel remained stuck in the ’70s: a disco symphony of earth tones, punctuated by those funky hexagons.

Meanwhile, BER was nowhere near completion: in fact, it only broke ground in 2006. The airport’s setbacks stemmed from incompetence, unrealistic ambitions, and a lack of oversight, all rooted in the insular mentality of Berlin’s administrative class. Small-town politics were likewise manifested in BER’s architectural, engineering, and managerial choices. In a big whopping surprise, the airport authority selected GMP as BER’s lead architect: the same firm that designed Tegel and that also planned Berlin’s new central train station. Local construction firms with little experience in large infrastructure projects were hired to supervise complex feats of engineering. The airport’s management board consisted of well-connected local heroes with scant knowledge of the aviation business. Meanwhile, village administrators from Brandenburg were tasked with issuing permits and enforcing regulations. Anticipating more headaches than benefits from BER, they relished any opportunity to identify violations that might delay the project. In one infamous example, 1,700 linden trees were planted at the airport, only to then be removed when officials uncovered an inconsistency between the subspecies of linden designated in the contract and the one that had actually been planted in the ground.

As for the airport’s design, BER is an exercise in too little, too late: actualizing the infrastructural ambitions of a bygone era. Toward the end of the 20th century, gargantuan greenfield airports located far from the city center were all the rage: witness Milan’s Malpensa and Montréal’s Mirabel, both of which emerged in the middle of nowhere, much to the regret of future traffic planners. Nowadays such greenfield projects are limited to cities with rapidly growing populations and to countries where authoritarian leaders leverage megaprojects to distract from ineffective governance. Neither of those attributes characterize Berlin: its population remains below pre-war levels and, that population having lived through a few too many authoritarian regimes, the appetite for grandiose construction projects remains muted.

On an aesthetic level, BER articulates the enlightened gravitas favored by Germany’s public-sector clients. GMP were a safe choice — the devil you know — and that risk-averse approach pervades the airport’s architectural moves, which are about as ambitious as the late-career bureaucrats who sponsored them. Solid, sober, and obsequiously inconspicuous, the terminal feels very much like a ‘safe space’ for civil servants: an understated aesthetic that one journalist dubbed a ‘tragedy in nut brown’. Sandstone floor tiles, wood paneling, and an unwavering loyalty to the good ol’ rectangle — no hexagons here! — give travelers the impression that they are entering, say, the Brandenburg Ministry of Weights and Measures.

On Halloween 2020 — a fitting date, perhaps — BER opened and a week later Tegel closed. Readers will excuse my agnosticism: after so many postponed inaugurations, it was difficult to muster much faith. In essence, BER is an airport that has fallen both out of place and out of time. The sense of a project that has shown up too late to the party is compounded by BER’s début in the midst of a global pandemic, at the tail end of what has been one of the most challenging years in the history of aviation. It evinces the parochial ambitions of a landlocked dictatorship that recently got wind of late-20th-century infrastructure fads. And snubbed by Lufthansa (no love is lost between Berlin and Germany’s national carrier, which favors Frankfurt and Munich), BER remains an airport hub without a hub airline. Schiphol has KLM, Charles de Gaulle has Air France, Heathrow has BA. And BER? For the German capital’s new airport, the closest thing to an anchor tenant is Easyjet, the British budget airline that is tottering on the edge of bankruptcy.

Berlin’s intellectuals relish the opportunity both to dissect the failings of their leaders and to construct a narrative of cultural decline indicative of broader afflictions to the German soul. On both counts, BER hasn’t disappointed: for decades, discussing BER has amounted to a never-ending self-criticism session, repeated a thousand times in print and over the dinner table. The airport also serves as a go-to topic for small talk: where the English discuss the weather to convert strangers into acquaintances, Berliners turn to BER. Among aviation planners, BER’s record of botched openings has become somewhat of a running joke. Yet those who know Berlin can’t deny that the airport pretty accurately reflects the city’s cultural peculiarities, particularly its relaxed attitude to industriousness and punctuality. In stark contrast to the rest of their countrymen, Berliners are a Volk inured to delays and disappointments. BER is a fitting emblem of the city that it serves: always pushing the boundaries of what it means to be fashionably late, and with an inimitable knack for avoiding strenuous activity, in the end Berlin still somehow manages to get the job done, sort of. Will the new airport be a success? As the Berliner says, mal kieken.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.