The fundamental, centuries-old architectural maxim — first draw, then build — is inverted in the recent book by Matthew Wells, Survey — Architecture Iconographies. Wells critically considers the history of drawings that record and recreate extant buildings, cities, and environments: drawing after building. Inaugurating the Architecture Iconographies series, published by Drawing Matter and Park Books, that presents drawing typologies in the history and practice of architecture, this first volume of the series appropriately begins with survey drawings, which expansively includes measured drawing, record drawing, as-built drawing, construction progress drawing, site drawing, and more.

The book is organized into three parts. Interleaved between the second and third is an unnamed visual intermezzo that portrays some of the drama of exploration and discovery within an archive, created from the collection of Drawing Matter. The first section, ‘Measuring Possibility’, begins with a critical review about the nature of survey drawings by looking across history from the Renaissance to contemporary times. Wells’s clear text offers insightful observations and little-known stories that make the survey drawings come alive as active practices.

The second section is composed of six thoughtfully selected case studies, ‘Surveys in Practice’, that range from the early 19th century to the present. The range of approaches to surveys by these well-known architects — John Soane, C.R. Cockerel, Hippolyte Lebas and Henri Labrouste, Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, Detmar Blow, and Peter Märkli — allow consideration of specific sorts of survey drawings in greater detail.

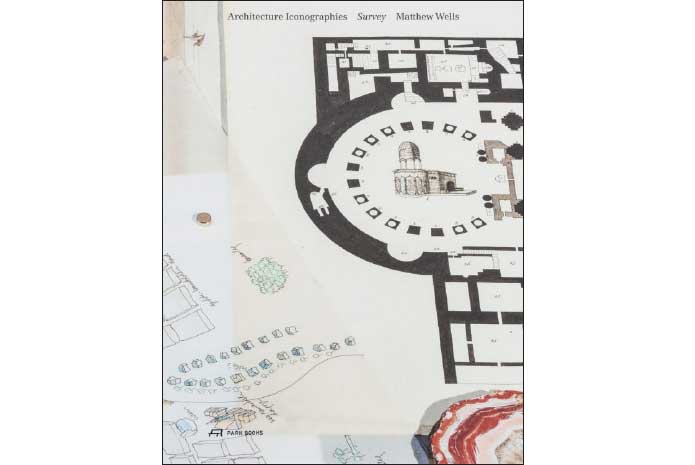

The third and final section reproduces 59 survey drawings from across the last five hundred years of predominantly European work, accompanied by captions. When not by the author, the brief explanatory texts are provided by contemporary architects about their own work. The selection shows that survey drawings use a broad range of drawing types, media, and technologies. The types of drawings include map, plan, elevation, section, detail, perspective, photography, and more idiosyncratic approaches, such as an 1809 circular panoramic view, Guy Debord’s psychogeography, and OMA’s ‘cartoon-like’ axonometric. While the selection includes some well-known drawings that would be notably absent if not included, many of the images have not been previously widely reproduced. The order of the plates is a bit of a mystery, an organization of apparently neither chronology nor geography. This survey of surveys provides a very pleasurable stroll that would be more useful with the addition of critical apparatus, such as indexes of artists, drawing subjects, and dates.

The high quality of the reproductions throughout Survey rewards the curious reader who enjoys closer examination. Some texts and images are intermittently turned to landscape format, allowing larger reproductions, but this may be an unnecessary distraction. The generous sizes of reproductions are very welcome, but it is unfortunate when a two-page spread has a portion disappearing into the gutter — especially when it coincides with the centerline of the drawing that often has important information. The large foldout of Arata Isozaki’s Re-ruined Hiroshima provides an especially impressive alternative. On the other hand, while a minor quibble, it may be excessive to enlarge Lewis Carroll’s Ocean-Chart by about 1.5 times its original size (7.5” × 5”).

Wells’s discussion of key attributes of survey drawings aren’t presented as essential unifying factors, but instead are family resemblances recurring across many but not all surveys. One key aspect is confronting the material presence of the building or landscape to be recorded. Its silent resoluteness resists the surveyor’s desire for easy acquisition of the thing’s dimensions and secrets, reminiscent of the character in Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum who chisels away a medieval building’s stone to make its proportions match the drawn ideal.

Wells reports the confrontation of surveyors with extant reality through dramatic stories and anecdotes. Journals of grand tour travelers, very different from today’s commercial mass tourism, record the humor and the travails of surveying structures. The wonder of archaeological discovery is countered by the hazards of, among other things, ‘near-fatal accidents involving falls from height’ (pl. 28). An engaging subgenre of survey drawings celebrates overcoming obstacles by illustrating the surveyor taking measurements while simultaneously documenting the results of that effort.

The distinction between travel sketches and surveys is primarily that of measure. Procedures of measurement are often directly or indirectly apparent in the final survey drawings. For example, some drawings show a plumb line hung from the outer edge of an entablature to provide a vertical regulating line from which to measure the molding (pl. 47). Another drawing includes a kite used to lift a rope to the top of a freestanding column (pl. 20). Wells notes that the camera lucida changed surveys into recording artifacts (59). Contemporary measurement by Lidar scanning produces uniquely engaging 3D documents (pl. 9–11).

An important aspect of survey drawings stressed by Wells is their degree of certainty, which highlights the limitations of measurement, scale, exactness, precision, and comprehensiveness. If the goal of surveys is accuracy, then what level is appropriate? Bodily pacing of the site provides a different sort of information than laser measurements. Even the choice of measure affects the outcome of surveys. The measures used by the original architect can reveal numerological meanings that substitution by another measure would obscure. What is prioritized in how a building is translated from the original site to the design studio through a survey is importantly discussed by Richard Krautheimer in his classic 1942 essay, ‘Introduction to an “Iconography of Medieval Architecture”’. Surveys not only record extant circumstances but are also instruments of design to imagine what could be in the future. Wells concludes that survey drawings ‘will never be complete’ (15) and ‘the limits of the drawings are the limits of our record and therefore of our world’ (22).

Survey drawing is ‘an act of humility’ (Thomas Padmanabhan in pl. 33) that constrains an architect’s willfulness. But surveys, Wells reminds us, also reflect and impose political and ideological views. One sees and records what is relevant to one’s own concerns. Rather than simply a conveyance of information, survey drawings are a tool that can be used to assert control over the artifacts that they record.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.