Text by Esther Gordon Dotson and Photography by Mark Richard Ashton,

Yale University Press, 184 pages, 2012, ISBN: 9780300166682

What do we mean when we speak of the “theatricality” of Baroque architecture? A reputation for exceptional performative agency grants building from this era a privileged role in broader discourses about art’s capacity to embody spectacle, but the operations and implications of this historical phenomenon are not always clear. Caroline van Eck has recently argued that studies on art and theatricality in the early modern period have either accounted for concrete instances of exchange between visual arts and the theater or highlighted works’ aptitude for structuring affecting scenarios (van Eck 2013: 8–23). In J.B. Fischer von Erlach: Architecture as Theater in the Baroque Era, Esther Dotson reconciles the two interests. By drawing connections between Fischer’s lifelong experimentation with formal strategies for staging festive or theatrical spaces and his tactics for conveying dramatic effects, the book introduces the outstanding architect of Vienna Gloriosa to a new generation of English-speaking readers.1 This roughly chronological series of descriptive case studies—derived from the manuscript left behind at the author’s death in 20092—attends equally to the form, context and impact of his most spectacular works. Though Dotson did not enjoy the opportunity to perform more extensive archival and historiographical investigations, her text suggests how future scholarship might address the forms early modern architectural theatricality took, while also probing the mechanics behind encounters between contemporary works and viewers.

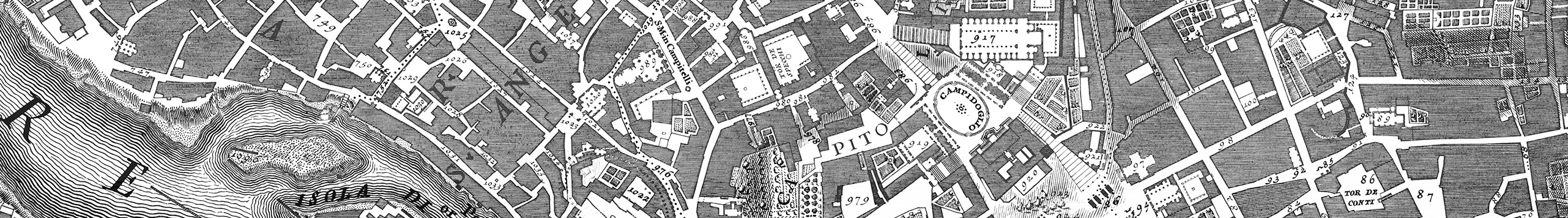

The interplay between architecture and experience in Fischer’s major projects is ably expressed through the book’s apt combination of evocative descriptions and photographs. Photographer and preface author Mark Ashton, who supplemented the manuscript with illustrations and a bibliographic essay, relates that his collaborator regarded text and image as equally crucial components of this project’s fundamentally descriptive objectives. Shooting without artificial lighting and exclusively from vantage points accessible in Fischer’s day, Ashton seeks to capture how Fischer coordinated audiences’ attention to the sequential unfolding of built forms and lighting shifts. This editorial orientation reflects Dotson’s sensitivity to historical viewing conditions and corroborates her larger narrative. By considering the architect’s designs in light of the texts, images, buildings, and experiences accessible to his wider public, both Dotson and Ashton illuminate Fischer’s methods for engaging audiences.

In the introductory chapter, “Architecture as Theater,” the author suggests that the dual influences of contemporary stage design and ephemeral architecture reveal themselves in the theatrical effects of Fischer’s permanent and temporary structures. This omnivorous approach to invention cemented the architect’s modern-day reputation for capriciousness and eclecticism. Yet by arguing that his theatrical idiom responded to patrons’ political and social objectives while manifesting the architect’s own artistic experiments, Dotson promises a new reading of Fischer’s idiosyncratic style. She introduces Fischer’s oeuvre with the Austrian National Library in Vienna. The work betrays the architect’s sensitivity to the interplay between light and shadow, deft fixing and ordering of views, and keen manipulation of viewer’s movements between and through interior and exterior spaces—all hallmark aspects of his mature designs. However, the author’s interpretation of the Library as representative of the various facets comprising Fischer’s unique understanding of architectural illusion is problematic, as authors since Hans Aurenhammer have noted the role his son Joseph Emmanuel also played in designing the building (Aurenhammer 1973: 147). Combining phenomenological description and briefer historical analysis, Dotson’s reading of the Hofbibliothek sets the methodological tone for the rest of the volume.

“Training and Early Work: Becoming an Imperial Architect” describes how Fischer’s studies in Rome and Naples under Johann Paul Schor informed the theatrical idiom he later perfected. Through Schor, the architect gained access to the circle of Queen Christina of Sweden, in Rome since her abdication in 1654. This learned patron of the visual arts and the theater also supported Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Nicodemus Tessin the Younger, and Giovanni Pietro Bellori. Fischer’s experiences in this world ensured his precocious ability to fuse the typically distinct formal idioms of ephemeral and permanent architecture, and to design with reference to multiple regional traditions. The monumentally ambitious plans for Schönbrunn Palace the architect presented to Leopold I in 1688 epitomize this versatility. Though only realized a decade later, and on a much smaller scale, the Habsburg’s suburban retreat still reflects how Fischer’s original designs reimagined the Sanctuary of Fortuna at Primigenia, Palestrina, with reference to the opera sets of his own era. The architect also drew from contemporary theater architecture and classical models like the Golden House of Nero to renovate paradigmatic regional forms in the cavernous entrance hall of the Liechtenstein stables at Lednice and his unusual oval ground plan for the ancestral hall of Althan Castle at Vranov nad Dyjí.

In “Another Ruler, Another City: Designs for Salzburg”, Dotson shows how Fischer’s mastery of urban scenography emerged in the Ursilinenkirche, Dreifaltigkeitskirche, Johanneskirche, and Kollegienkirche he designed for Prince Archbishop Johann Ernst Graf Thun and other patrons throughout the 1690s. All except the Kollegienkirche were built under conditions unconstrained by extant architecture or surrounding topography. Fischer was therefore free to perfect a model for what Dotson terms the “urban proscenium” (Dotson and Ashton 2012: 66)—a dramatic passage between oblique and frontal angles of approach, often framed by triumphal arches, in which the viewer emerges from darkness into light. The formula drew from Girolamo Fontana and G.F. Grimaldi’s theater designs and the form of the Piazza del Popolo in Rome. Yet by propelling audiences between profane and sacred realms, it also suggested the deeper forces these holy spaces contained. The architect meanwhile experimented with the pleasurable effects of disorientation at Count Thun’s Kleßheim retreat. His central-plan garden pavilion—the so-called Hoyos Stöckl—lacks any static frontal view, while the dynamically recessing, projecting, and interpenetrating volumes of the palace that later joined it reinterprets Louis Le Vaux’s1656–1661 Vaux le Vicomte with a new, kinetic vigor.

Dotson contends that the energetic style and talent for architectural spectacle Fischer consolidated in his Salzburg work solidified his burgeoning reputation among aristocrats in the capital. “Imperial Vienna: Patronage of the Courtiers” shows how inventive projects for Habsburg insiders brought the architect’s idiosyncratic strategies for engaging audiences to Joseph I’s attention just as the Emperor was entertaining new architectural ambitions. Though the city palace of Prince Eugene of Savoy is typically interpreted as a monument to the patron’s decisive role in quashing the 1683 Siege of Vienna, Dotson observes elements of parody in the unusual dimensions and iconography of the entrance portal reliefs. Capricious treatment of classical models also surfaces in the sculptural program for Schönborn-Batthyány Palace, and the façades of the Trautson Palace and Bohemian Chancery, which each invert the conventional hierarchy between structural and super-structural elements. By restoring order in more conservative interiors, Fischer mitigated the disorientation these transgressive exteriors occasioned and demonstrated his talent for composing stimulating architectural experiences.

“Imperial Vienna: The Emperor as Patron” details how the affective aptitude of Fischer’s mature style shaped the Bauwelle, or “building deluge,” following Vienna’s deliverance from the Siege and transformed the capital into an urban stage manifesting Habsburg power. Daringly located outside the city’s fortifications, the votive Church of St. Charles Borromeo, or Karlskirche, Emperor Charles VI dedicated to his name-saint and plague intercessor after Vienna recovered from the pestilence of 1713 embodied the era’s optimism. Here the architect connected shifting lighting effects with the progressive unfolding of the building’s iconographical program, experimenting with new ways of linking form and allegorical content. In this sense, the work epitomized Fischer’s strategies for moving audiences—physically, emotionally, and psychologically—in a manner attentive to the “human dramas” his works contained (Dotson and Ashton 2012: 51). The church occupied a triumphant position in the newly-secure and rapidly expanding suburbs. Perpendicular to the axially-aligned Imperial stables, Filiberto Lucchese’s Leopoldinertrakt, the Imperial library, and the Michaelertor, it commanded a full vista of the palace complex Fischer and his son realized during the first decades of the eighteenth century. By visibly connecting his numerous Imperial commissions within and across Vienna’s rapidly transforming landscape, the architect created an enduring theater for representing Habsburg dynastic glory.

Fischer’s magisterial Entwurff einer historischen Architektur of 1712 disseminated and indeed immortalized the image of the city he helped remake. In “A Learned Architect,” Dotson argues that this first comprehensive world history of architecture also offered an unprecedented paradigm for combining classical, biblical, and even non-European theatrical motifs within a unified architectural idiom. She additionally asserts that the work demonstrated how to contrive erudite programs for permanent and ephemeral monuments: the entire fourth tome is filled with original designs showcasing a heterogeneous, recombinatory method for learned invention. In this way, the Entwurff…, or “Outline,” indicated a framework for activating architecture’s dramatic impact to convey politically-charged messages. Luigi Ferdinando Count Marsigli’s 1702 Danubius Pannonico Mysicus and his Roman colleague Athanasius Kircher’s 1646 Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae and 1652 Oedipus Aegyptiacus furnished Fischer with his most important models for infusing a monumental work of empirical research with pro-Habsburg rhetoric. For instance, the author incorporated Charles VI’s polysemous personal device within a universal story of building through the Entwurrff’s Herculean, Solomonic double-column leitmotif. Foregrounded in Kircher’s hieroglyphic disquisitions and his 1679 Turris Babel, the symbol epitomizes an emblematic vision of the edifice and shows how printed architecture might dramatize narratives of cosmic dimensions.

More detailed consideration of Fischer’s sources and his impact would further justify Dotson’s argument for the architect’s outstanding status among the numerous designers then engaging architecture and theater. Her account of his cultural and intellectual context is likewise incomplete. More obscure, drafted set designs by Girolamo Fontana and G.E. Grimaldi and the ephemeral architecture of Peter Paul Rubens’ 1642 formative but hardly unique Pompa Introitus are cited as crucial sources for Fischer’s “theatrical” idiom, while exchanges with colleagues like the stage-set treatise author and ceiling frescoist Giuseppe Galli da Bibiena go unmentioned. Such omissions may stem from the book’s unusual publication conditions, as such information is rarely missing from the numerous comparative studies (Lorenz 1992), iconographical readings (Polleroß 1995) and intellectual histories (Lorenz 1992; Kreul 2006) that have recently dominated the bibliography. Ultimately, Dotson’s work uncovers unexpected new facets of Fischer’s practice—aspects which invite more intensive research.

In her epilogue, “Architecture and Motion”, the author asks if, since Fischer’s era lacked a critical lexicon for phenomenology, “it is justifiable without anachronism to speak of [the effect of] motion,” (Dotson and Ashton 2012: 153) or indeed other devices underpinning the architect’s spectacular idiom. The query engages a key issue for discussions of the “theatrical” nature of the Baroque, and architectural studies in general: how might we historicize the link between architecture and experience? Hans Sedlmayr’s often problematic work on Fischer arose from similar questions about how the mysterious meeting of form and content was understood. Dotson’s treatment of the often intangible link between monuments and their experiential effects does not merely clarify the long-debated priorities behind the architect’s “eclectic,” (Polleroß 1998: 146) “universal,” (Aurenhammer 1973: 168) or “theatrical” style; by illuminating how early modern architects imagined new possibilities for mediating relationships between audience and edifice, these insights also lay groundwork for future critical studies.

Notes

1 Dotson’s book joins Hans Aurenhammer’s J. B. Fischer von Erlach (1973) as the only general introduction to the architect’s oeuvre in English.

2 Photographer Mark Richard Ashton subsequently edited the manuscript.

References

Aurenhammer, H 1973 J. B. Fischer von Erlach. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dotson, E G and Ashton, M R 2012 J. B. Fischer von Erlach: Architecture as Theater in the Baroque Era. New Haven: Yale University Press.

van Eck, C 2011 The Visual Arts and the Theater in Early Modern Europe. In: van Eck, C and Bussels, S (eds.) Theatricality in Early Modern Art and Architecture. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Kreul, A 2006 Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach: Regie der Relation. Vienna: Anton Pustet Verlag.

Lorenz, H 1992 Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach. Zürich: Verlag für Architektur.

Polleroß, F 1995 Fischer von Erlach und die Wiener Barocktradition. Vienna: Böhlau Verlag.

Polleroß, F 1998 ‘Architecture and Rhetoric in the Work of Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach’ in: Reinhart, M (ed.) Infinite Boundaries: Order, Disorder and Reorder in Early Modern German Culture. Sixteenth Century Studies and Essays, vol. 40. Kirksville, MO: Truman State University Press.