Introduction

The travel guide is one significant medium that reveals how the identity of a place is shaped by the tourist industry, since the imagery of a country’s attractions feeds into its national narratives. This paper focuses on the complex interrelations between landscape construction and identity politics in tourism development, as represented and promoted by travel guides in 1960s Cyprus, where tourism was a major priority of a ten-year development and modernization plan.1 The juxtaposition and interpretation of landscape images from Cyprus’s postcolonial and colonial years found in popular travel guides and other publicly disseminated media associated with tourism reveals the intertwined discourses of decolonization, leisure politics and national modernization in 1960s Cyprus, and follows the changing imagery of landscape. This paper examines landscapes that underwent a number of transformations on a physical, urban or historical level in order to meet the interests of the tourism industry. It investigates the politics behind tourism landscape construction and representation and suggests that it can be an instrument for affirming ideologies and shaping identity (Harris 1999; Kolodney and Kallus 2008; Kolodney 2012), especially through the development of tourism.

Modernization and Leisure Politics in Postcolonial Cyprus during Nation-Building Processes

In 1878 the British took over Cyprus and ended the Ottoman domination of the island which had begun in 1571. The British rule lasted until 1960 when, after the anti-colonial struggle, Cyprus gained its independence. Greece, Turkey and Britain acted as guarantor powers for the young state. Nation-building in the early Cyprus Republic took place in a complex political context. On the one hand, colonial influences were palpable: the British maintained two military bases in Cyprus; colonial buildings often housed the new state’s institutions; and legislative, educational and administrative processes had roots in the recent colonial past (Pyla and Phokaides 2011). In addition, Cyprus’s developing tourism industry often relied on joint investment funds with a strong British element, and the greater part of income came from British tourists.

On the other hand, the new state’s attempts to nurture nationhood and social unity were focused on balancing tensions between the two distinct communities: Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots, the latter representing around 18 percent of the population by the time of independence. Both communities were characterized by nationalism and a deep connection to their respective ‘motherlands’ (Papadakis, Peristianis and Welz 2006). Despite these efforts, little of the political turmoil was alleviated, and after inter-communal fights in 1963, Turkish Cypriots withdrew to enclaves. Conflict culminated in 1967, when Turkish Cypriot leaders formed a separate administration, and finally resulted into the island’s violent division in 1974 (Papadakis 2005).

For these reasons, the early postcolonial condition was characterized by an attempt by the new state to distance itself from Britain’s influence in the areas of law, administration, economy and so on — which was not always feasible, as colonial structures were still present — and the need for the two communities to achieve compromises, given their nationalist tendencies (Bryant 2006).2 The new state’s nation-building agendas were based on the view that economic prosperity through radical modernization would ease tensions and create the new national profile of independent Cyprus. Therefore, modernization policies and initiatives, including three five-year plans for economic development (1962–76), became promising and untainted symbols for constructing and affirming the country’s new identity.3 Tourism was the top priority of these five-year plans, based on the recommendations of an expert committee, appointed by the UN, that had been in place since 1960.4 One of the main goals of the first plan (1962–66), whose primary purpose was to rationalize budgets and increase revenues, was to develop infrastructure attractive to foreign investors. Relevant projects included reconstructing ports and road networks, upgrading the airport in the capital city of Nicosia, and creating new telecommunication, electricity and water infrastructures, principally dams (Aristeidou 2010). The plan also aspired to exploit the island’s natural resources through agriculture, industrialization and tourism. An indicative example showing the extent to which modernization and tourism, among other areas, were becoming central to the new state’s self-representation is a collection of stamps published in 1967, boasting images of projects from the first five-year development plan. These images depict a contemporary dam, a newly constructed motorway and the Hilton Hotel in Nicosia, among other developments (Fig. 1).

Collection of stamps dating back to 1967, dedicated to the ‘First Development Program’, 1962 to 1966 (Mihranian 2005: 98).

Tourism Development in Colonial and Postcolonial Cyprus and the Construction of Tourist Landscapes

The foundations of the tourism industry in Cyprus had begun to develop in the 1930s while still under British rule, but the large-scale development of tourism in Cyprus began only after the island’s independence. Factors impeding foreigner influx in the first decades of the 20th century included the island’s poor accessibility, the lack of appropriate tourist infrastructure, high temperatures and diseases like malaria (Ioannides and Apostolopoulos 1999). During the 1940s, the colonial government set up a committee for tourism development to devise a plan for the island, mainly around road infrastructure and sea transport, but few of its objectives materialized. As a result of the initiatives taken by the British, the number of tourists began to grow. From 1950 to 1955, the average annual increase was 11.6 percent, while from 1956 to 1959, during the anti-colonial conflicts, the numbers fell. In the 1950s, most of the tourists came from the United Kingdom, though a significant number of visitors also came from Egypt and Israel (CTO 1962: 54) (Fig. 2).

The number of visitors to Cyprus, according to country of origin, between 1950 and 1961 (CTO 1962).

In colonial times, most tourist projects were carried out in mountainous areas, specifically the Troodos mountains. Fashionable mountain resorts attracted mostly summer visitors from the Middle East, especially Egypt, while minor hill resorts served the needs of locals. Seaside resorts, such as Kyrenia, were beginning to develop, and were popular principally for British people wintering in Cyprus (Christodoulou 1992: 139). The illustrations of travel guides of the colonial era — which will be further analyzed in the main body of this paper — demonstrate that Cyprus at that time was promoted for its pristine, romantic and picturesque identity of places and people.

In the early postcolonial years this profile was reversed, as the new Cypriot government placed a heavy emphasis on the modernization of tourism infrastructure, with the clear goal of making the island an international tourist destination. By adopting certain measures and policies to promote tourism, Cyprus followed the lead of other Mediterranean countries. An advisory committee, made up of representatives from several tourism-related organizations, was set up. The committee was to create an overview of perspectives for tourism development and acknowledge areas of priority. The committee’s development plan for tourism recommended, among other things, the government-funded erection of new hotels and the renovation of existing ones, as well as campaigns to promote the island’s beauty abroad. It also advised training Cypriots in tourism business administration, leading to the foundation of the Central Hotel Training School in 1965, and its later successor the Hotel and Catering Institute (HCI) in 1969, a joint project between the Republic of Cyprus, the United Nations Development Program and the International Labour Office (ILO) (Sharpley 2003).

Such tourism policies introduced by the government signaled the transformation of the island into a major Mediterranean destination for summer sun, and the focus shifted from the traditional hill resorts in the Troodos mountains to coastal resorts in Kyrenia and Famagusta (Sharpley 2003). During this period, tourism grew rapidly; it became seasonal, and the UK had already emerged as the principal market. Annual arrivals, which totaled just 25,700 in 1960, exceeded 264,000 by 1973, representing an average annual growth rate of over 20 percent. Kyrenia and Famagusta accounted for 58 percent of accommodation and 73 percent of arrivals. Tourism contribution to the island’s GDP grew from around 2.0 percent in 1960 to 7.2 percent in 1973 (Sharpley 2003).

The Golden Sands Hotel and the Hilton Hotel, both completed in 1969, are two characteristic examples of the government’s direct involvement in tourism development. The Golden Sands Tourist Center, co-supported by British Airways and Cyprus Airways, was constructed in Famagusta on state-owned land. The government commissioned a British firm, Garnett Cloughley Blakemore & Associates, to design the center in collaboration with a local firm. The goal was to firmly place Cyprus on the Mediterranean tourist map by combining an international hotel brand with signature design (Phokaides and Pyla 2012) (Fig. 3).

At the same time, an ‘urban tourism’ equivalent began to develop, attracting not only leisure tourists but Europeans and Americans who visited the island for business purposes. The construction of the Hilton Hotel, in the capital city of Nicosia, was part of this process. The decision to build this hotel was finalized during President Makarios’s visit to the US in 1962, when he met with President Kennedy, and subsequently also with Conrad Hilton. Both welcomed the idea of making Cyprus an official member-state of the internationally renowned hotel chain. The Cyprus Tourism Development Company was created to manage the project.5 The government incurred the cost for the erection of the hotel and its equipment, and then leased the property to the Hilton Company for a period of twenty years (Fig. 4).6

With the active contribution of President Makarios, these projects were clearly a priority in the government’s modernization and nation-building agenda, because the construction of international chain hotels such as Hilton and Golden Sands supported the expansion of corporate networks associated with a globalized tourism culture. In addition, such hotel buildings were widely regarded as symbols of modernity (mainly because of their design and amenities) and emblems of luxury for the countries hosting them, monumentalizing Cyprus’s ambition to gain international prestige and thus boosting its national pride.7 The building boom in the tourism industry of the 1960s, which led to the construction of twenty new hotels between 1960 and 1969, and the modernization of existing ones8 (Kitsikis 1966: 194), along with the broader significance of tourism for the image of modern Cyprus, is also clearly in evidence in a 1966 issue of the Greek architectural journal Architektoniki. This issue, which included an extensive presentation of Cyprus’s contemporary architecture (Kitsikis 1966), shows typical examples of newly built tourism projects, such as the Grecian Hotel in Famagusta and two recreation pavilions with swimming pools (Figs. 5, 6 and 7).

Grecian Hotel in Famagusta. Architektoniki, 55 (1966): 69.

The swimming pool at the Ledra Palace Hotel. Architektoniki, 55 (1966): 62.

The swimming pool at the Platres Hotel. Architektoniki, 55 (1966): 63.

In the same issue, an article with title ‘Tourism in Cyprus’, written by C. Montis, head of the Department for Tourism, provides an overview of tourism development in Cyprus, stressing tourism’s importance for the contemporary building industry. After mentioning the island’s natural attractions, Montis gives a brief account of available accommodation infrastructure (e.g., the Constantia Hotel in Famagusta and the Hilton Hotel under construction). The article is accompanied by relevant illustrations depicting natural, archaeological and modern sites (Fig. 8). These trends signal the transformation of tourism models in the 1960s, and more specifically, the migration from the picturesque scenes of colonial times to modernized landscapes, which was the focus of the developing tourist industry (Fig. 9).

A presentation of contemporary Cyprus: an aerial photo of Kyrenia, along with views of Bellapais Abbey in the Kyrenia mountains and the Constance and King George Hotels in Famagusta. Architektoniki, 55 (1966): 103.

Representations of Colonized and Independent Cyprus: The Shift from ‘Traditional’ to ‘Modernized’ Landscapes

How was this shift from ‘colonial’ to ‘postcolonial’ tourist landscapes reflected in images circulated by popular media associated with tourism? What were the mechanisms behind the transformation of landscape imagery, and in what ways was that transformation linked to contemporary identity politics? A comparison of Cyprus’s colonial image with its modern independent-nation image through representations of landscapes, as conveyed in travel guides, provides some answers. One English-language guidebook of the colonial epoch is Across Cyprus, first published in 1937 and reprinted in 1943 and 1945 by Travel Book Club. It was written by Olive Murray Chapman, an English traveler who explored Cyprus, Madagascar and other remote and ‘primitive’ destinations. This book was part of a series of travelogues by Chapman, including Across Iceland and Across Lapland, where through text, photographs and watercolors, she describes her experience of unknown places and narrates her contact with indigenous people.

Also, in 1928, the Armenians Haigaz and Levon Mangoian, the official photographers of the colonial government of Cyprus, began to publish postcards of the island, which became very popular (Marangou 1996: 23). In 1942, the Mangoians compiled The Island of Cyprus—An Illustrated Guide and Handbook, with photographs by Haigaz himself and with articles on the history of the island. Only one edition of the book was published, but its illustrations were reprinted in other widely published travel guides, such as Romantic Cyprus, written by Kevork Keshishian, which included images by other contemporary photographers as well. Romantic Cyprus was the longest-selling tourist guide, published in seventeen editions between 1945 and 1993, already reprinted and revised nine times by 1962. It was translated into Greek, French and German.9 These guidebooks featured natural landscapes, traditional ceremonies, farming activities in the countryside and abandoned medieval castles (referred to as ‘fairytale’ scenery), emphasizing the ‘unspoiled’ and picturesque identity of places and people (Figs. 10 and 11). They also often included orientalist representations, such as camel caravans making their way through the Mesaoria Valley (Fig. 12).

Landscapes in the travel guidebook The Island of Cyprus. Photos by Haigaz and Levon Mangoian (1947). Photo by the Mangoian Bros.

People arriving at Stavrovouni monastery for the Easter fair. Photo by Olive Murray Chapman (1945: 145).

Camel caravan in the Mesaoria Valley. Photo by Olive Murray Chapman (1945: 48).

Scholars have recently explored how the characterizations of Cypriot lands and people as pristine and exotic were not unintentional in these guidebooks. Hercules Papaioannou analyzes images taken by British photographer J. Thompson at the dawn of the British rule, and investigates how these depictions representing ‘the colonial gaze’ met the interests of colonial propaganda (Papaioannou 2014). Papaioannou argues that through these photographs, Cyprus is not only represented as a place of ancient origin, with traditional values and beautiful landscapes, but also as a wild and fertile land that awaits taming and cultivation, a mission of the colonization project. Nikos Philippou discusses a National Geographic travelogue on Cyprus of 1928 and says that although manifestations of modernity were already evident by then, the illustrations again ‘purify’ Cyprus, to fit with the already established colonial view of Cyprus as a backward country (Philippou 2014).

Constructing the Present: Modernized Landscapes Become the New Tourist Destinations

After Cyprus became independent, the fact that the tourism industry was moving away from ‘colonial’ settings and toward the new modernized landscapes can be understood as due to those leisure politics that aspired to an internationally established model of Mediterranean tourism. It can also be understood as part of a broader nation-building goal to promote modernization as the symbol of Cyprus’s new profile. Equally, the transformation of Cyprus was not only expressed as a shift of focus in tourism projects from mountains to beaches, but also as the construction and promotion of a new identity based on constructed environments in place of the former seemingly natural ‘unexploited’ spaces (Aisopos 1999; Kaika 2006). What is more, new infrastructure projects, such as highways, dams and ports, constructed to comply with the standards of this model, became another kind of tourist attraction. Maria Kaika explains how such infrastructure projects introduced a new way of experiencing the countryside and nature. She focuses on the construction of the Marathon dam in Greece during the 1920s and argues that dams became new tourist destinations that:

Signaled yet another qualitative shift in the way the urban dweller experienced and appropriated the countryside in many parts of the Western world: no longer in search of the beauty of a divine and pristine nature, but in conscious pursuit of the splendor of a man-made, pride-inducing ‘second’ nature. (Kaika 2006: 295)

A typical example of ‘artificial’ tourist settings that were connected to Cyprus’s modern identity is the photograph of the artificial lake Saittas in the Troodos mountains, found in the guidebook Aphrodite’s Realm of 1962 (Fig. 13). The image shows people enjoying refreshments by the lake, while the caption says that the lake is ‘the site of a government experimental agriculture station including the principal viticulture station in the island’ (Parker 1962: 174). Illustrations in Motoring in Cyprus, published in 1967, also show natural landscapes along modern highways and beside new ports (Fig. 14; see also Fig. 29). Again, images praising Cyprus’s ‘divine’ natural beauty are being overtaken by the artificial environments of technological progress, as a constant reference to modernity. Industrial development in Cyprus also played a role in the promotion of the island as independent and modernized. Trade expositions and industrial procedures were promoted as tourism highlights.10 The focus was no longer the images of farmers working in the countryside. In contrast, we see many images of work sites and factories with workers and their supervisors (Fig. 15).

Lake Saittas, an artificial lake in the Troodos mountains, from the guidebook Aphrodite’s Realm (Parker 1962: 174). Courtesy of Press and Information Office, Nicosia.

The port of Famagusta, featured in the guidebook Motoring in Cyprus (1967: 94). Courtesy of Press and Information Office, Nicosia.

Images presenting contemporary industries, featured in the guidebook Motoring in Cyprus (1967: 40–41). Courtesy of Press and Information Office, Nicosia.

Constructing the Present: Modern Architecture as the New Tourist Landscape

Beatriz Colomina identifies the emerging systems of communication that have come to define 20th-century culture — the mass media — as the true site within which modern architecture is produced (Colomina 1994). She considers architectural discourse as the intersection between a number of representation systems: drawings, models, photographs, books, films and advertisements. She therefore argues that within modernity, the site of architectural production literally moved from the street and into photographs, films, publications and exhibitions. Modern architecture images in travel guides of postcolonial Cyprus are a case in point. They are also an example of the constant dialogue between representations of the tourism industry in mass media and identity politics.

Modern architecture was first introduced in Cyprus around 1930, when an increasing number of professional architects educated in Europe established their practices on the island. The modernist aesthetic was evident primarily in institutional and residential architecture (Pyla and Phokaides 2009). After independence, ‘modern architecture became more of a symbol and an instrument for both decolonization and modernization’ (Pyla and Phokaides 2009: 37). Modernist ideas began to characterize new tourist infrastructure and buildings, such as hotels or urban open spaces, and the principles of adaptability and standardization of modern architecture were adjusted to the requirements of Cyprus’s climate. These case studies constitute a valuable field for the investigation and analysis of modern architecture as an instrument by which to construct and assert a national identity (Pyla and Phokaides 2009). The role of modern architecture in this ‘nation-building mission’ is also corroborated by its appearances in travel guides of the postcolonial period, not only in depictions of tourist projects and resorts, but also of urban landscapes. In addition to the modernist hotel complexes and recreation centers, travel guides of the 1960s feature images of apartment blocks, industrial buildings and scenes of everyday life in the city center, considered as representative images of modern Cyprus (Figs. 16 and 17).

Modern apartment block, from the travel guidebook Aphrodite’s Realm (Parker 1962: 19). Photo by Fisher.

In this way, modern architecture operated as an icon of Cyprus’s tourist branding and offered — along with archaeological site attractions and cosmopolitan beaches — the appropriate link between the island’s precious past, or its natural beauty, and its new, modernized identity. Modern architecture not only became the ‘focal point’ and was conspicuously promoted in travel guides through images of modern buildings, but also often constituted the background in the images of various urban landscapes, archaeological sites or scenes of everyday life. The angle of the photographic lens often encompassed, in addition to the main object, some symbol of modernity: ancient walls were framed by modern buildings, beaches by modernist hotels (Figs. 18 and 19). Also, depictions of archaeological sites, appearing in the front covers of travel guides such as Motoring in Cyprus, included figures of contemporary people (Fig. 20). Illustrations consistently refer to the present, thus fostering the country’s modern Mediterranean identity. Images of non-urban settings in colonial guidebooks, often depicting the timelessness of nature, had been replaced by representations that included elements of modernity.

Nicosia’s medieval walls accompanied by modernist buildings in the guidebook Aphrodite’s Realm (Parker 1962: 23). Photo by Mikis.

Cover of the guidebook Motoring in Cyprus, published in 1967 by Zeno Publishers, Nicosia.

Reconstructing the Past: Restored Archaeological Landscapes

Another recurring theme in the travel guides about Cyprus is the place of historical significance, such as archaeological landscapes and monuments. Although at first sight these are perceived as related to the past, recent scholarship explores how through their restoration and exposition as tourist sites, they have become instruments for implementing contemporary national ideologies. Yannis Hamilakis argues that archaeology and its representations are intimately linked to national imagination, and that archaeology is an official ‘device’ of western modernity supporting the material evidence of a nation (Hamilakis 2007). He traces a link between nationalism and procedures embedded in tourism, and recognizes that producing and promoting ‘national themes’ through excavation and exhibition in archaeological sites is a process of selective ‘construction’ of a nation’s identity.

Cyprus’s archaeological heritage can be traced back to the Neolithic period (the Khirokitia settlement) and features significant classical, Hellenistic and Roman monuments, Byzantine churches, Gothic cathedrals and Venetian castles from the medieval era, Ottoman mosques and hans, and monuments from the British colonial period. Careful observation of archaeological elements in colonial and postcolonial travel guides uncovers a selective emphasis on specific archaeological destinations and periods of history, which can also be verified through examining which sites in Cyprus were restored.

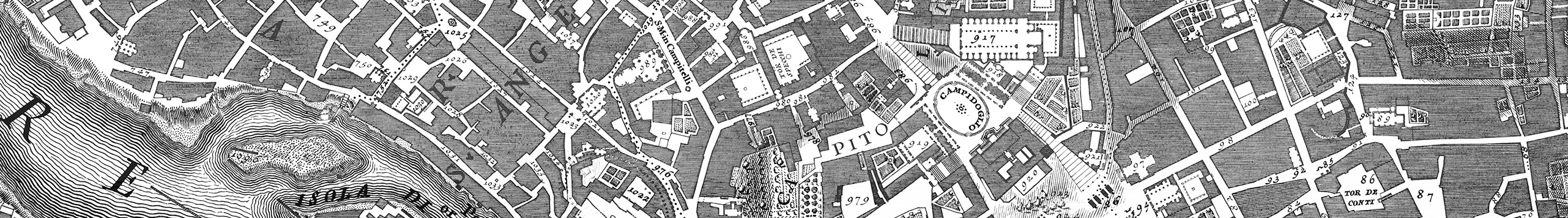

The restoration of monuments during the late colonial period (especially after World War II) focused on those of medieval times, in other words, on past colonial regimes, in a bid to nurture a colonial national identity in line with current affairs. The Department of Antiquities, established by the British in 1935, renewed its interest in the restoration of archaeological sites of this particular period and went on to re-organize the Cyprus Archaeological Museum, founded in 1882. A variety of monuments, including Byzantine churches, medieval monuments such as the walls of Nicosia, Gothic cathedrals in Famagusta and some Turkish hans, were restored, while there seems to be no evidence of restoration at classical or Hellenistic monuments (Limbouri 2005). For instance, in 1890 excavation work began that revealed part of the ancient Greek city of Salamis, now considered to be one of Cyprus’s most important heritage sites. That work was suspended in 1891, well before the Department of Antiquities was established, and was not to be resumed until after 1952 (Limbouri 2005).11 The archaeological site was opened to the public only after independence.

The selective re-construction of particular parts of the island’s history was the result of a broader agenda held by the colonial regime. As recent research highlights, British authorities wanted to emphasize the island’s European medieval historical, architectural and cultural heritage and to avoid references to Cyprus’s classical Greek period, which was by then associated with Greek Cypriot nationalism and would awaken Greek Cypriots’ desire for independence and reunion with Greece. The identity politics in question are now also being discussed in the historiography of British colonial architecture in Cyprus, where symbolic references to a selective past are remarked upon (Pyla and Phokaides 2009; Given 2005). While from the beginning of the 20th century until World War II, references to Cyprus’s classical period were used in public buildings to promote the role of colonization in reconnecting the country to its glorious ancient past, after World War II, when the first movements of independence and reunion with Greece began, neo-classical references were replaced by morphological elements of the medieval era (Pyla and Phokaides 2009). In the same way, in line with contemporary politics, travel guides of late colonial times, which included mostly pictures of medieval monuments, are also testament to the interest towards previous colonial periods (Figs. 21 and 22).

The Abbey of Bellapais, in the guidebook Romantic Cyprus (Keshinian 1945: 57). Photo by W.H.G. Popplestone.

Medieval walls of Famagusta, from the guidebook Romantic Cyprus (Keshinian 1945: 81), drawn by F.M. Drake.

In the first decade of independence, when the Department of Antiquities was reorganized, major restoration projects of the classical and Roman periods began, such as the archaeological site of Salamis and part of Kato Pafos’s Roman theatre. Scientific staff included western archaeologists (mainly German and French). The reconstructed classical archaeological sites became the new popular tourist product, aiming to satisfy the demands of foreign tourists. These tourists would supposedly ‘consume’ the ancient past with the same fervor that they sought beaches, modern cities and resorts (Fig. 23). Recent scholarship has discussed how connections between modernity and classical antiquity were commonplace for Mediterranean countries with ancient heritage (Wharton 2001; Athanasiou 2012).

The Salamis site, in the guidebook Cyprus, the Pearl of the Mediterranean, published in 1974 by Zavallis Press, Nicosia. Photo by Mangoian Bros.

These classical sites strengthened the country’s brand, not only helping boost tourism revenues — the sites were a popular trend of the tourism industry at that time — but also functioning as ‘national themes’, as Hamilakis calls them. They thus contributed to a selective construction of Cyprus’s modern identity by forging a connection to its Ancient Greek past.12 Sites such as Salamis were featured in images on the cover of travel guides, such as Motoring in Cyprus, as well as in their content, as in the title of the guidebook Aphrodite’s Realm (1962). These two examples epitomize the tourism industry’s profitable practice of promoting the link between modern Cyprus and its classical heritage.

Revisiting Colonial Resorts

How the production of landscape reflects the transition from colonialism to the nation-building era has also been investigated in the case of Haifa (Kolodney and Kallus 2008). The authors of that study use the term erascape to describe the mechanism of fundamentally transforming the landscape, which involves erasing an existing landscape to make way for another, motivated by the sociopolitical agendas of both colonial and national authorities. In the case of post-independence Cyprus, by a similar process, a new identity, also connected with nation-building, was established in tourist destinations that had been previously identified with the colonial period. The transformation of pre-existing resorts is further evidence of the shift from colonial to postcolonial tourist landscapes. These resorts, popular in colonial times, were re-constructed to adhere to a new modernized model. Characteristic examples of such ‘landscape re-construction’ mechanisms are open-space reconfigurations at hotels previously associated with colonial times, such as the refashioning of the garden landscape around the Ledra Hotel in Nicosia and the Forest Park mountain resort in the village of Platres, both sites that were popular in the 1940s and were re-branded in independence-era travel guides.

Situated at the center of Nicosia’s old city, the Ledra Palace Hotel had been designed by the German–Jewish architect Benjamin Günsberg, and owned by the Greek Cypriot company Cyprus Hotels Limited. The hotel had been inaugurated on October 8, 1949, in the presence of the British governor, Sir Andrew Wright. Its design is representative of British colonial architecture, and is fused with gothic elements. Its garden was initially based on classic English landscape design, with symmetrical and geometric patterns and exotic elements such as palm trees. It also included theme gardens, such as the Jasmine Garden, which was the hotel’s main attraction. Ledra Palace’s garden attracted high-class local British and Greek audiences, as well as other wealthy foreign tourists.

In 1964, the Greek-Cypriot architect Fotis Kolakides was assigned the redesign of part of its open spaces, by also introducing a swimming pool. In this way, the ‘classic-style’ garden transitioned to ‘modern’, and included several other symbols of contemporary-style outdoor space and activities: open bars, cabanas, changing rooms. The new garden’s design was characterized by a modernist aesthetic with local references. The swimming pool became the new ‘place to be’ not only for tourists, but also for the local middle class, and a site that had once been reserved for high society became open to a wider range of visitors (Demetriou 2012) (Fig. 24).

A similar process took place in the Forest Park Hotel, in the village of Platres on Troodos mountain. A popular resort during colonial times and originally built in 1936, Forest Park was owned by the same company as Ledra Palace, and was the first hotel in Cyprus to follow international specifications (Fig. 25). Kolakides, the same architect, redesigned its open spaces, after taking into consideration the beautiful view to the south, the existing tall pine trees and the sloping grounds. He tried to adjust the new landscape design, which once more included a swimming pool and other amenities of outdoors modern lifestyle, to these conditions (Kitsikis 1966: 63) (see Fig. 7).

Forest Park’s outdoor spaces, from the guidebook Motoring in Cyprus, published in 1967 by Zeno Publishers, Nicosia.

The above interventions could be associated with the emergence of an international trend of introducing an outdoors aspect to modern resorts, also found elsewhere in the Mediterranean, and are also the result of the need to maximize commercial gain. However, they also represent instances of a new landscape identity for resorts — powerful symbols of change, as they did not take place in new sites, but in destinations that were already famous tourist attractions. Therefore, the mechanism of reforming an ‘English garden’ into a garden designed according to modern trends was also part of the broader agenda of reinventing Cyprus’s identity through landscape projects, as were the resulting new performances, further discussed below.

Experiencing Landscape: A Passage from the Romantic to the Modern Traveler

As already discussed, a closer look at colonial travel guides reveals that Cyprus was promoted as a picturesque and romantic destination, untouched by modern civilization. The traveler of colonial times was the ‘escapee’ of urban life who was drawn to Cyprus by its ‘back-to-nature’ message. This is manifest in the promotion of intact landscapes in mountain villages, pre-industrial manual labor processes in the countryside or donkeys as a means of transport (Figs. 26 and 27). The identity shift in tourist settings brought about by the country’s independence inevitably implied new cultures of enjoying them. Consequently, the profile of a visitor to Cyprus changed, from the romantic wanderer of colonial times to a contemporary individual who craved the Mediterranean experience while holding onto comforts and modern amenities: Hilton hotels, organized beaches, pool bars, tennis courts. This newly introduced model of leisure entailed a culture of mass consumption, and representations of landscape advertised specific consumption practices. For instance, images of sandy beaches also included people enjoying food in tavernas (Greek-Cypriot traditional restaurants) or having cocktails by the pool (Figs. 28 and 29). These observations underline the catalytic role of travel guides in bringing a modern Mediterranean leisure culture to 1960s Cyprus.

Scenes of everyday life in the countryside, from the guidebook Romantic Cyprus (Keshinian 1945: 168). Photo by Edwards Studio, Limassol.

Pristine landscape from the guidebook Romantic Cyprus (Keshinian 1945: 118). Photo by Edwards Studio, Limassol.

‘Sandy Beach’ in Kyrenia, from the guidebook Aphrodite’s Realm (Parker 1962).

Moreover, Cyprus’s transportation infrastructure began to reflect the advent of fast-paced sightseeing. The title of Motoring in Cyprus reflects the motor vehicle’s perceived contribution to the new travel experience. In the book’s introduction, the Minister for Commerce is quoted as recognizing ‘the possibilities for a motorist to make excursions and enjoy the beautiful landscape […] in an island which is called, a motorist’s paradise’ (Motoring in Cyprus 1967: 19). In this way, the new infrastructure networks, intended for the modern person with little time to spare, contributed to the construction of a new travel culture, as also evidenced by the proliferation of automobiles and motorbikes (Figs. 30 and 31). Consequently, these road-tripping trends involved a new way of experiencing the landscape, through the moving motorcar.13

Road infrastructure from Motoring in Cyprus travel guidebook, published by Zeno Publishers, Nicosia (1967: 83).

Road infrastructure and the coastal front of Larnaca, from the guidebook Motoring in Cyprus, published by Zeno Publishers, Nicosia (1967: 179).

New Cultures of Leisure and Local Populations

The new landscape images for tourism that prescribed travel behaviors to foreigners, based on the model of the contemporary Mediterranean culture of leisure, also nurtured new ways of outdoor living for locals. These gradually became naturalized as part of contemporary Cypriot behavior in public spaces. New designs for a tourist landscape included all modern outdoor living fetishes and corresponding leisure activities. Their promotion as popular tourist attractions allowed the foreigner to ‘feel at home’ and Cypriots to enter new ‘places to be’: especially for the middle and upper class people who could afford to spend their leisure time in private open spaces, such as a hotel’s pools or tennis courts. The tourist landscapes infused with these leisure cultures also marked a departure from traditional formal and informal behavior in Cyprus, which contributed to the further reinvention of local identity: Hilton or Ledra Palace pools became popular spaces for socializing, where Cypriot women and men laid their semi-naked bodies in the sun, enjoyed cocktails and mingled with foreigners (Fig. 32). Consequently, this new lifestyle also brought about new mixed-gender interactions in public space. The open spaces of hotels also hosted numerous ‘imported’ public events, such as wedding receptions (a newly introduced custom) parties, beauty contests14 and car expositions (Demetriou 2012: 1).

Conclusion

This paper traced elements of modernization, the ‘national mission’ of independent Cyprus in the 1960s, in the construction and representation of tourist landscapes catered by contemporary travel guides. The comparison of pre- and post-independence images reveals how they unveiled leisure politics as well as nation-building agendas. Photographic illustrations constitute important evidence of their time, and therefore can be used to explore potential links between identity politics and landscape construction by underlining their role in shaping place identity, traveler behavior and local culture.

Furthermore, my analysis builds upon and further extends current scholarship about how global tourist trends were embraced by national and local governments in the Mediterranean region during the postwar years in order to achieve economic and political stability and how these trends participate in the construction of a modern image (Aisopos 1999; Alifrangkis and Athanassiou 2013; Wharton 2001). Cyprus constitutes an interesting case study in this particular context, as tourism after independence developed under complex socio-political and national circumstances. The case of Cyprus thus contributes to our understanding of how similar tourist policies in the Mediterranean region generated different national narratives, depending on the country’s background.

During my investigation, it also became clear how similar mechanisms of landscape construction and representation became the means to achieve opposite sociopolitical agendas (national or colonial). Neither Cyprus’s presentation as a virgin territory during colonial times nor its postcolonial profile as a modernized nation can be disassociated from their political contexts. Similarly, the ‘construction’ of different pasts for Cyprus and their promotion via images of archaeological sites reveal how colonial and national regimes manipulated the archaeological heritage to achieve political goals.

Illustrations of landscape, as seen in the travel guides of Cyprus during the colonial and then the independence eras, possess symbolic and political dimensions. Therefore, this analysis supports recent scholarship that analyzes the construction and representation of landscape as an agent of power (Harris 1999: 434; Kolodney and Kallus 2008; Kolodney 2012), and that analyzes, especially through the vehicle of tourism development, how landscape imagery can become an instrument for affirming ideologies and shaping identity. This study also indicates the need to further extend the critical historiography through an interdisciplinary approach regarding the complexities of landscape construction and representation during tourism development, especially in postcolonial contexts.

Notes

- On perspectives of landscape representation and politics, see, for example, Peleman and Notteboom (2012) and Kolodney (2012). [^]

- Rebecca Bryant analyzes Cyprus’s postcolonial peculiarities, and explains how modernization and nation-building in independent Cyprus were different from other postcolonial countries in the decade of the 1960s. She exposes intertwined discourses of continuing colonial influence, modernization and nationalism. Panayiota Pyla and Petros Phokaides also examine how after independence the new government expressed an ambivalent attitude towards the British colonial architectural heritage: for instance, the new state demolished the colonial secretariat building, in order to build a new administrative complex on the same site, while it used a primary symbol of colonial oppression, the former British ‘Government House’, as the new Presidential Palace, after superficially refashioning it. As Pyla and Phokaides observe, ‘Such diametrically opposed strategies only underline the young state’s ambivalence towards the colonial legacy’ (Pyla and Phokaides 2011: 91). [^]

- Cyprus’s path to becoming modern had already begun during British rule but had been advancing at a much slower pace. [^]

- Participation of foreign experts not only in financial but also in ‘educational’ aspects of modernization unavoidably and deliberately affected — as in the case of other contemporary Eastern Mediterranean countries supported by the West — the orientation of its new identity (Alifrangkis and Athanassiou 2012; Simeoforidis 1999). The new identity of Cyprus was thus constructed through its firm anchoring to western culture. [^]

- ‘Το Χίλτον’, Χαραυγή, 13 January 1963. [^]

- Following the Golden Sands example, this hotel was also designed by the foreign architectural firm Raglan Squire & Partners, who had experience in designing other Hilton chain hotels in North Africa and the Middle East, in collaboration with a local firm. [^]

- Annabel Wharton, in her book Building the Cold War: Hilton International Hotels and Modern Architecture (2001), demonstrates how building Hilton Hotels in Egypt, Istanbul, Athens and other capitals during the Cold War, served Cold War Politics. The presence of a Hilton Hotel in those cities raised the national pride of the country that hosted them, as they were widely perceived as symbols of modern leisure and luxury, and thus also constituted a space where the native society desired to spend time. [^]

- Furthermore, in 1961 Cyprus’s hotel bed capacity was 4,306, but had grown to 13,050 by 1973 (Aristeidou 2010). The daily press acknowledged tourism industry growth and potential (see ‘Η τουριστική βιομηχανία’, 1960; ‘Τί γίνɛται’, 1962; and ‘Η κυβέρνησις’, 1967). [^]

- For the purposes of this essay, I will analyze material from the fourth edition of the book, from 1951, before Cyprus’s independence but when tourism had begun to develop. [^]

- A few scenes regarding the industrial development of Cyprus are also found in travel guides of colonial times, also promoting colonial power and its modernization efforts. [^]

- Even in cases where guidebooks referred to Salamis, they described it as a Roman settlement, i.e. of another colonial period. [^]

- The construction of Cyprus’s modern identity through connection with its ancient Greek origin took place at a time when any aspirations to reunite with Greece had already faded away. [^]

- David Peleman and Bruno Notteboom (2012) also investigate how roadside landscapes that were constructed in Belgium during the interwar period were conceived to serve the motorist’s gaze. [^]

- A subject for another paper would be to study how these new performances, such as beauty contests or wedding receptions in the modern tourism landscapes, resulted in the further essentialization (rather than the emancipation) of women. [^]

Acknowledgements

A special thank you goes to all anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and constructive feedback on this paper. I would also like to thank the Cyprus Tourism Organization for offering access and assistance to archival material.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Y Aisopos, (1999). From the ’60s to the ’90s: Disengaging from ‘Place’ for a New Beginning In: Y Aisopos, Y Simeoforides, Landscapes of Modernization. Athens: Metapolis Press, pp. 36. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2013.838285

S Alifrangkis, E Athanassiou, (2013). Educating Greece in Modernity: Post-War Tourism and Western Politics. The Journal of Architecture 18 (5) : 699. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2013.838285

I Aristeidou, (2010). Οδοιπορικό της Ανάπτυξης της Ανπρου από την Ανɛξαρτησία και Μɛτά -Μαθήματα για το Μέλλον. Nicosia: Theopress.

E Athanassiou, (2012). The Mechanical Reproduction of Cultural Heritage: Shifting from Touristic Areas to Public Spaces. Paper presented at Sixth Conference of the International Forum on Urbanism (IFoU): TOURBANISM. Jan. 25–27, Barcelona : 1.

R Bryant, (2006). On the Condition of Postcoloniality in Cyprus In: Y Papadakis, N Peristianis, G Welz, Divided Cyprus: Modernity, History, and an Island in Conflict. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, pp. 47.

O M Chapman, (1945). Across Cyprus. London: Travel Book Club.

D Christodoulou, (1992). Inside the Cyprus Miracle: The Labours of an Embattled Mini-Economy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. 2

B Colomina, (1994). Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture as Mass Media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

CTO (1962). Cyprus Study for Tourist Development. Nicosia: Cyprus Tourist Organization.

O Demetriou, (2012). From the Green Line to the Dark Room: a Photo-History of Ledra Palace Hotel. PCC Photo Brief 1 (1–2)

M Given, (2005). Architectural Styles and Ethnic Identity in Medieval to Modern Cyprus In: J Clarke, Archaeological Perspectives on the Transmission and Transformation of Culture in the Eastern Mediterranean. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 207. Levant Supplementary Series 2.

Η τουριστική βιομηχανία δνναται να αποτɛλέσɛι τον Θɛμέλιο λίθο της ɛυημɛρίας της Ανπρου [The tourism industry can become the foundation of Cyprus’s financial flourishing]. Ελɛυθɛρία, January 24 1960 : 3.

Η κυβέρνησις θα αναπτνξɛι ɛκτάσɛις χαλίτικης γης [The government will develop on state-owned land]. Μάχη, June 22 1967 : 7.

Y Hamilakis, (2007). The Nation and Its Ruins: Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

D Harris, (1999). The Postmodernization of Landscape: A Critical Historiography. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 58 (3) : 434. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/991537

D Ioannides, Y Apostolopoulos, (1999). Political Instability, War, and Tourism in Cyprus: Effects, Management, and Prospects for Recovery. Journal of Travel Research 38 (1) : 51. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/004728759903800111

M Kaika, (2006). Dams as Symbols of Modernization: The Urbanization of Nature between Geographical Imagination and Materiality. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 96 (2) : 276. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2006.00478.x

K Keshishian, (1945). Romantic Cyprus: A Comprehensive Guide for Tourists and Travelers. 3rd edition Nicosia: Mark & Moody.

A Kitsikis, (1966). Architektoniki Journal. Athens: Technografiki. 1 (55)

Z Kolodney, (2012). Between Knowledge of Landscape Production and Representation. The Journal of Architecture 17 (1) : 97. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2012.659913

Z Kolodney, R Kallus, (2008). The Politics of Landscape (Re) Production: Haifa Between Colonialism and Nation Building. Landscape Journal 27 (2) : 173. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3368/lj.27.2.173

E Limbouri, (2005). Αποκαταστάσɛις Μνημɛίων στην Ανπρο από την Ίδρυση του Τμήματος Αρχαιοτήτων το 1935 ɛώς το 2005. Unpublished thesis (PhD). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

L Mangoian, H Mangoian, (1947). The Island of Cyprus: An Illustrated Guide and Handbook. Nicosia: Mangoian Bros.

A Marangou, (1996). Haigaz Mangoian, 1907–1970. Nicosia: Cultural Center of the Cyprus Popular Bank.

B Mihranian, (2005). Kυπριακά Γραμματόσημα 1880–2004: Ιστορία και Πολιτισμός. Nicosia: Ministry of Transport and Public Works.

Motoring in Cyprus: Your Guide to Cyprus. Nicosia: Zeno publishers.

Y Papadakis, (2005). Locating the Cyprus Problem: Ethnic Conflict and the Politics of Space. Macalester International 15 (1) article 11. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol15/iss1/11.

Y Papadakis, N Peristianis, G Welz, (2006). Modernity, History and Conflict in Divided Cyprus: An Overview In: Y Papadakis, N Peristianis, G Welz, Divided Cyprus: Modernity, History, and an Island in Conflict. Indiana: Indiana University Press.

H Papaioannou, (2014). John Thomson: Through Cyprus with a Camera, between Beautiful and Bountiful Nature In: L Wells, T Stylianou-Lambert, N Philippou, Photography and Cyprus: Time, Place and Identity. London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 13 pp. 13.

P Parker, (1962). Aphrodite’s Realm: An Illustrated Guide and Handbook to Cyprus. Nicosia: Zavallis Press.

D Peleman, B Notteboom, (2012). Picturing the Perfect Setting: The Mediation of Landscape and the Road Engineering Project in Belgium, 1925–1962. The Journal of Architecture 17 (1) : 69. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2012.659911

N Philippou, (2014). The National Geographic and Half Oriental Cyprus In: L Wells, T Stylianou-Lambert, N Philippou, Photography and Cyprus: Time, Place and Identity. London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 13 pp. 28.

P Phokaides, P Pyla, (2012). H Heynen, J Gosseye, Peripheral Hubs and Alternative Modernisations: Designing for Peace and Tourism in Postcolonial Cyprus. Proceedings of the 2nd International Meeting of the European Architectural History Network. Brussels Koninklijke Vlaamse Academie van België voor Wetenschappen en Kunsten : 442.

P Pyla, P Phokaides, (2009). Architecture and Modernity in Cyprus. EAHN Newsletter 2 [Newsletter of the European Architectural History Network].

P Pyla, P Phokaides, (2011). Ambivalent Politics and Modernist Debates in Postcolonial Cyprus. The Journal of Architecture 16 (6) : 885. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2011.636994

See the Pearl of the Mediterranean: Cyprus, an Illustrated Guide and Handbook of Cyprus. Nicosia: Zavallis Press.

R Sharpley, (2003). Tourism, Modernisation and Development on the Island of Cyprus: Challenges and Policy Responses. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 11 (2–3) : 246. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09669580308667205

Y Simeoforidis, (1999). Collective Visions and Isolated Trajectories In: Y Aisopos, Y Simeoforides, Landscapes of Modernization. Athens: Metapolis Press, pp. 42.

Τί γίνɛται, τι θα γίνɛι δια τον κυπριακόν τουρισμό [What has been, is being and will be done for tourism in Cyprus]. Ελɛυθɛρία, January 17 1962 : 2.

Το Χίλτον. Χαραυγή, January 13 1963

A J Wharton, (2001). Building the Cold War: Hilton International Hotels and Modern Architecture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.