Introduction

How to (re-)conceive the writing of architectural history today? This has been, perhaps, the most enduring question behind the ever-evolving work of Beatriz Colomina (Figure 1).

Historians often take pride in ‘breaking new ground’. Typically, this means formulating uncharted territories for research, discovering hitherto ignored characters, or unearthing obscure archives that nobody had heard of before. Colomina’s work, however, is largely based on the inverse of this approach: the gaze turns towards the interior of the discipline to re-examine some of the most canonical narratives, characters, and objects of 20th-century architecture through a contemporary lens. To attempt this historiographical act of defamiliarisation is to allow oneself to be surprised anew by what seemed as easily categorisable knowledge — to make vividly clear how the mythology of (modern) architecture has been routinely sanitized of life’s ‘complexities, tensions, and innovations.’ Through what Colomina calls an ‘intra-canonical outlook’, much of her scholarship has targeted unpacking what has frequently always been in plain sight, but (for one reason or another) has remained unacknowledged, excluded, suppressed. In the following interview, she traces the intellectual origins of her methodology and argues for the potential of a ‘queer’ historiography, one that does not simply ‘make space’ for exception, but one that has come to terms with architecture’s inherent schizophrenias, perversions, and weirdness.

Conducted a few months before the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, this conversation was meant to coincide with the publication of Colomina’s latest book X-Ray Architecture, the culmination of her long-standing obsession with the intersection of architecture and illness. The profound ‘strangeness’ of our lived experience since then has not only added a new layer of relevance to this incisive scholarly endeavour but has also come to confirm Colomina’s thesis that architectural history, just like the lives of the canonical architects who shaped the various conceptions of the built environment we inhabit today, is ‘actually much queerer than we think’.

Kotsioris:Even though we have worked together for almost a decade, I don’t think I have ever asked you this directly — what were the major forces that have shaped your work as a historian?

Colomina:In many ways I feel that my experiences of New York in the early 1980s, at a time the city was very different, have shaped who I am. Of course, I was born and studied in Spain. And for a very significant part of my life, about the first one-third, I lived under the dictatorship of [Francisco] Franco, which also defined me in fundamental ways (Figure 2). My university years in Barcelona were post-1968, but because of the dictatorship, 1968 kept going. Everyone was heavily engaged with revolutionary politics. In fact, the most politically committed people I found at the Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura at the University of Barcelona turned out to be in the area of history and theory, as well as urbanism. Less so in design, with a few notable exceptions, such as Oriol Bohigas. The historians had this very strong connection with Italy. They identified with Manfredo Tafuri, not only because of his writings but also because of his political orientation. So, this combination of scholarship and activism is very important to understand who I am intellectually and where I come from.

Kotsioris:How did politics in the United States compare to your experience of it in Spain?

Colomina:When I first arrived in New York, everything felt so different. There seemed to be no political struggles here. I was struck by how little engagement there was on the part of the students. Ronald Reagan had just been elected. Don’t you think students will be setting the school on fire?! A couple of years later, Columbia University students started to mobilize for divestment from South Africa but it didn’t seem to impact the school of architecture in any significant way. Likewise, Edward Said was revolutionizing postcolonial politics right there at Columbia, but there seemed to be no impact on architecture. I attended his seminars for two years, but I didn’t see anybody from architecture. My experience had been that as a student you are as engaged with the politics as you are with the books, if not more. In Spain it had been more, because we were in a really terrible situation.

But just a few months after my arrival in the city, there was a completely different war in terms of politics: witnessing the AIDS crisis and the first students of architecture to die of it at Columbia, including my roommate’s boyfriend. It was devastating. A whole generation of theorists and scholars, like Craig Owens, whom I had invited to speak in my classes, was dying. This was a defining moment, in so many ways. There was all this outrage with an emergency not being taken seriously by anybody in the country. Silence was indeed death, in the crucial words of the ACT UP mantra (Figure 3).1 It’s hard to explain now, but it was like coming from one kind of a struggle to another. There were urgent lessons for architecture but not yet being learned, another kind of silence.

I have obviously heard you talk before about your enduring interest in illness, tuberculosis, and modern architecture, but have never heard you talk about the impact of the AIDS crisis in New York.

Colomina:The former was an intellectual obsession before the latter. In late 1980, I was a visiting fellow at the New York Institute for the Humanities, where I was totally inspired by Susan Sontag, who was a senior fellow and had recently published Illness as Metaphor (1978). I started to see modern architecture in terms of all the illnesses, real or imagined, from agoraphobia to tuberculosis. AIDS threw me in the middle of a real situation, just a year later. To have seen one of those devastating situations with your own eyes really marks you. But as a historian I think I had to think through the longer history in order to face, or even understand, the architecture and urbanism of AIDS.

Kotsioris:In addition to being a historian, you’ve noted that you are ‘also an architect, at least on paper’.

Colomina:Yes, I started at the Escuela Tecnica Superior de Arquitectura in Valencia, which followed a system similar to the German polytechnics. You had to pass everything in one semester or you would not be admitted to the next. This included all kinds of difficult technical and scientific courses. In the first semester, we were 2,000 students, and a few women. By the third semester only 20 and no other women left. The architecture school had been moved outside the city centre to avoid conflict and protests — very typical of the period after 1968. The attitude was something like: ‘Let’s move them out to prefabricated barracks in the middle of nowhere and let them protest among cows and sheep!’ It was horrible! I decided to move to the school in Barcelona, but it was complicated. In those years of dictatorship, you were supposed to go to school in the place where your parents lived, if there was a university there. It was a way of controlling the population. But I managed to escape the usual control, and Barcelona was very exciting to me because it offered other ways of seeing architecture.

Kotsioris:Do you think this mindset has shaped your historical methodology? The way you assemble evidence?

Colomina:Maybe, I’m not sure. What does one ever know about oneself? What I do know is that I was very attracted to the historical discourse. There were two lines at the school: one in design and the other in urbanism. This was only for the two final years of study out of five. I chose urbanism because it was more discursive. At first, I didn’t understand anything. The first textbook we were thrown at was Tafuri’s Theories and History of Architecture (1972). Can you imagine? I have always been kind of obstinate, so I really wanted to understand what Tafuri said. I kept at it precisely because it was difficult. I didn’t worry much about the other classes. But this one required work. I thought ‘okay, this is not really my natural thing’. Precisely because it was not, though, I somehow became more engaged with it, more obsessed.

Kotsioris:How did you eventually pivot from design towards history?

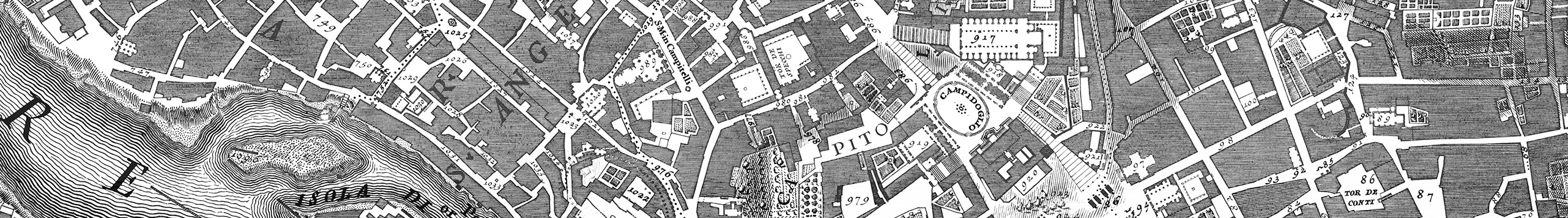

Colomina:Through the Department of Urbanism in Barcelona, and the Department of History and Theory, which was actually called ‘Composición’, believe it or not. In particular, through people like Ignasi de Solà-Morales and Josep Quetglas. All of them were very politically engaged. That is why so much of my work goes back to Tafuri and the school of Venice, where I would go regularly, buy books and attend lectures. We drove through the night to listen to Tafuri’s bi-weekly lectures in Venice (Figure 4). We also had friends there, recording everything that was happening at IUAV [Università Iuav di Venezia]. Tafuri, Aymonino, and Rossi were constantly being invited to Barcelona to speak. So that was my education — very much Italian-heavy.

Was Marxism the dominant theoretical framework, in that respect?

Colomina:Marxist theory was very important to us, but it was Tafuri’s version of it, which is already deviating quite a bit from the books. In Spain there was always an association between architecture, theory, and politics. With a friend of mine, Ada Llorens Geranio, we did the translations of Tafuri’s ‘Austromarxismo y ciudad’ (1975a) and ‘Socialdemocracia y ciudad en la Republica de Weimar’ (1975b) in 1975 (Figure 5). These two essays were very, very important to me to understand where Tafuri was coming from, what his sources were. So, I did a lot of research into the topic. This led to a period when I became extremely interested in Red Vienna. In fact, my first article, ‘Vienna between the Wars’, was published in this little magazine I used to edit with friends of mine, including Josep Quetlas who was really the ring leader. It was called Carrer de la ciutat, which was a beautiful enigmatic expression and for those in the know, a political address. We did 12 issues between 1977 and 1980 (Figure 6).2

The far left cover is of Manfredo Tafuri’s Spanish translation of Teoria e storia dell’architettura (1972 [1968]) that was taught in Barcelona in the 1970s. The other two covers are of the Spanish versions of Tafuri’s essays ‘Austromarxismo e città: “Das rote Wien”’ (1975a [1971]) and ‘Socialdemocrazia e città nella Repubblica di Weimar’ (1975b [1971]), translated by Beatriz Colomina Elías and Ada Llorens Geranio.

In an article you’ve argued that ‘[i]n Giedion’s practice, there is no distinction between the work of the architect and that of the historian; they are both engaged with equal status as collaborators in the modern project’ (Colomina 1999: 464). Did you find these two hats at odds, as Tafuri would?

Colomina:No. And this alleged incompatibility of the two hats is not Tafuri’s most compelling argument. In Barcelona you still had to graduate with an architectural project, calculate the structure, everything. There was no escape. It was not like in Venice, or the AA in London, where you could simply graduate with a written thesis, or with a story! Despite the fact that we were so influenced by Tafuri, there was this understanding that the architect who writes is also an architect. That architecture is a discursive practice. That what we did was no less of architecture than building. As Peter Smithson says, architecture is kind of a conversation, and stories are part of its practice. We claimed writing as part of architecture. That’s why I started working in the Department of History and Theory in Barcelona right after I graduated. I had a full-time teaching position, which was actually under the Department of Urbanism, which really meant history and theory.

Kotsioris:Apart from Tafuri, which other architecture historians did you study? Which ones did you look up to?

Colomina:I didn’t have a very conventional education in history, if you think about it. We were all into Tafuri and the Venice School, but we didn’t read much of [Reyner] Banham, for instance. I love Banham but he was simply not part of the curriculum in Barcelona. We knew everything about France and Italy and very little about the United States or the UK. In that regard, being at Columbia as a visiting scholar from 1981 to 1983 had a huge impact on me. I was in the seminar of Robin Evans, who was a visiting professor for a semester. Banham came and gave a whole lecture series about the silos. Brilliant. At a certain point, even Leonardo Benevolo was teaching. Not so brilliant. All these people became very significant to me. I got to see them in person, be in their classes. That is where I got another education, one I didn’t get in Spain.

Kotsioris:You briefly touched upon the time that you spent as fellow at the New York Institute of the Humanities, at the time run by Richard Sennett. How did that period affect your architectural thinking and research?

Colomina:The Institute for the Humanities was extremely important to me. But also, Columbia. Both of them, in different ways. The Institute was a very sophisticated place, I learned a lot about interdisciplinarity there. It was the opposite of Columbia in that sense. The work of Wolfgang Schivelbusch (1977) on the railway, for example, was inspiring. Or Carl Schorske (1980) with his work on the end-of-the-century Vienna. And of course, Susan Sontag. I realized that all these people were working with novels, with music, with paintings … They were mixing all kinds of documents. I found that fascinating. It was this mix of disciplines that was so intriguing. Outside these academic settings, I was also gradually picking up things from everywhere around Manhattan. The feminist theory of the 1970s and the ’80s was very much alive. There was a group of very strong feminist theorists, particularly in art and film. I became friends with people like Rosalyn Deutsche, Barbara Kruger, and Jane Weinstock, who became a film director. They opened my eyes to the whole field of feminist studies and feminist film theory. You can see how Laura Mulvey’s (1975) ideas of the male gaze informed my writings on the windows of modern architecture and the interiors of Adolf Loos. That was the moment I was more influenced by other disciplines.

Kotsioris:How do you recall the ferment of architecture’s so-called ‘theory moment’ of the 1980s in New York? At places like Columbia?

Colomina:Because my formation in history and theory was so strong in Barcelona, I found — believe it or not — people at Columbia and the Institute of Architecture and Urban Studies kind of naïve sometimes. There was this group around Revisions: Papers in Architectural Theory and Criticism, the publication series, and sometimes I’d think to myself, ‘What are they saying’? In Barcelona, the history and theory coming from the school of Venice had been for me like my mother’s milk. I knew it backwards and forwards, and they seemed to have just discovered it. Surprisingly, compared to the Italian tradition, New York seemed to be so far behind. In a sense, the rise of so-called ‘theory’ was a reaction against this backwardness. It was not antagonistic. It’s just there were other questions that seemed urgent. The birth of Assemblage and the ‘gang’ around it, of which I was part, was simply because we had other things to do.

Kotsioris:What was your first major undertaking as an architectural historian?

Colomina:When I was an assistant professor in Barcelona there was this opportunity to do research on Ricard Giralt Casadesús, an urbanist who was very active in politics and was an editor of an important magazine in the 1920s and 1930s in Barcelona. That was my introduction to archival work. His family had donated all this material to the library of the Colegio de Arquitectos de Barcelona and they needed somebody to organize the archive. I went there with this grant from the Colegio and for a year I did this systematic research on his work. That research turned into a report, which, funnily enough, eventually turned into my first book. By that time, I was already in New York and Ignasi de Solà-Morales alerted me that someone was putting together a book with all the work I had done. There was some kind of agreement, again organized by Ignasi, and my name ended up in the book as well and I wrote the introductory essay. I didn’t care too much, but Ignasi insisted on it, and, as with so many things, I have come to know he was right and that labour in the archives is a crucial thing. I have remained close to the archive ever since.

Kotsioris:You’ve once written that ‘[t]he pleasure of the historian is, after all, the (voyeuristic if not fetishistic) pleasure of the archive’ (Colomina 1994b: 168).

Colomina:I totally stand by that! The discovery of “the pleasure of the archive” actually happened when I went to work on Le Corbusier in 1984. I spent a lot of time at the archive of the Fondation in Paris over the years, ostensibly to do research on L’Esprit nouveau. I’ve never been obsessed with whether something was this year or that year, but with all kinds of other small things, things you come across that strike you for some reason and work against the grain of the usual interpretations. Threads you get curious about and pull a bit, before you even know why, unravel the usual assumptions and expose other dimensions of figures and projects. A bit like psychoanalysis. That was a discovery. For me that was ‘the archive’. Le Corbusier become something else. It was there I first found this pleasure for the document, and for barely hidden secrets.

Kotsioris:It’s a kind of detective’s work, isn’t it?

Colomina:It’s totally a detective’s work! But you can get lost in it too. It’s endless.

Kotsioris:If the archive is the moment of pleasure, then there is the painful moment of reassembling the evidence. How do you go from sorting through all this material to actually having a topic at hand?

Colomina:In Le Corbusier’s archive, I started like everybody else by looking for something particular, the journal L’Esprit nouveau. And because of what I had read about it, I was at first looking for a letter of [Walter] Gropius, or a letter of [Theo] van Doesburg as evidence of a so-called network of the avant-garde. There was very little of that. What I was finding was so baffling, so different than what I had expected, so different than what anybody had written about L’Esprit nouveau. After going through multiple boxes of what I initially considered as ‘junk mail’, I realized that Le Corbusier doesn’t answer these people because he doesn’t care so much about them. What he’s totally crazy about is getting a photograph of this lamp or that turbine. Publicity and modern advertisement fascinated him. He starts writing Vers une architecture on the basis of catalogues and photographs he’s taking from them. He organized his texts like film scripts with little images, and he would call out the ones he could not find: ‘Where is the lamp?’ or ‘Where is the turbine?’ or ‘Where is the postcard of Pisa?’ He’s thinking of his arguments visually, like in a film, and then filling out the text later. Suddenly I could see it all so clearly. Now I had a topic. The architecture of media. Modern architecture as media.

Kotsioris:Privacy and Publicity (1994a), which came out of your dissertation, focused on two of the most canonical figures of the historiography of modern architecture: Loos and Le Corbusier. Why them?

Colomina:In Barcelona, when we were editing Carrer de la ciutat, we paid a lot of attention to the canonical figures, but there was the understanding that this is not the whole story. That’s why I first wanted to do my dissertation on illnesses, and tuberculosis, and this whole thing. But everybody said ‘no, you have to do something more architectural!’ Loos had always been very important to me and I had written on him for 9H and other magazines around 1982, so it was heading that way. But then somehow, I don’t know why, Le Corbusier came into the picture around 1983–84. I was not aware of it at the time, but it was a few years before 1987, the centennial of his birth, and there were a lot of preparations underway. It was a very lucky coincidence. Bruno Reichlin, Jean-Louis Cohen, and Stani[slaus] von Moos, all whom I knew from hanging out together in the archives of Le Corbusier, invited me to write for their centennial catalogues. I also started to be invited to give lectures at Harvard, Yale, Delft, London, and Berlin, among other places. This also led to going to Princeton for the first time as a lecturer to replace Alan Colquhoun’s class on Le Corbusier for a semester in 1986. At first, I kept telling myself, ‘they must be making a mistake’. I totally had the imposter syndrome. But as you know, I am still at Princeton.

Kotsioris:How do you reflect on this earlier work of yours in light of contemporary debates on revisiting, expanding, questioning, rejecting, or even demolishing the canon?

Colomina:People could accuse me of focusing on canonical figures, like Le Corbusier, or Loos, or the Eameses. But the reason I have paid a lot of attention to these figures is because I am interested in looking at them in a non-canonical way. I think that is my role precisely. This realization became part of the introduction for X-Ray Architecture (2019). Instead of adopting Henry-Russell Hitchcock’s ‘extra-canonical’ approach (Banham 1996: 283) — just adding external figures to the canon — I am interested in the idea of the ‘intra-canonical’ outlook. I think that’s exactly what defines me — going to what is the most canonical and undermine it so that another view can emerge. But at the same time, the X-Ray book is also full of these weirdos that you have never heard about, these ‘side-men’ and ‘side-women’ and all these characters that have never seen the light in architectural history but are never tangential. So, X-Ray, like the other books, it is both canon and anti-canon.

Kotsioris:In the introduction to Sexuality and Space (1992: vi), you write: ‘To be admitted is to be represented. And space is, after all, a form of representation. The politics of space are always sexual, even if space is central to the mechanisms of the erasure of sexuality’. I find this last sentence to have a lot of contemporary resonance, inside and outside university campuses. What was the instigator for this project at that particular moment?

Colomina:That sounds like a very 1990s sentence, doesn’t it?! The Sexuality and Space conference I organized at Princeton in 1990 coincided by chance with the first acknowledgement that gay couples could have university housing together. This eventually extended to health insurance, and other things. But it took a long time for universities to get to that. Many of the ideas on sexuality for that symposium and book came from Jacqueline Rose’s work. Diana Fuss, a professor of English at Princeton working on feminism, was also a very close colleague. And there were these new gay and lesbian studies programmes starting at every university. At that point I really thought that all this was going to become very, very important. In my imagination, it would affect all the curriculums across disciplines immediately. It hasn’t quite yet. This past year, with the centennial of the Bauhaus, I’ve tried to undermine the received view and uncover what I call ‘the perversions of the Bauhaus’. Queering the history of architecture is part of my programme. It’s not just to add queer architects to the history of modern architecture, but to queer the history itself. It’s actually much queerer than we think, and that’s much more interesting. The queering of architectural history has yet to happen.

Kotsioris:Is that because any deviation from ‘normative’ historiographical involves a re-learning curve? Because ‘perversions’ still cause uneasiness?

Colomina:Some people get very nervous. Others think that I use the word ‘perversions’ in a negative sense (Figure 7). But I use it in the same way that the queer movement adopted the word ‘queer’, a word that had been put down and was repressed. It is an effort to do something that moves the field along. I am precisely embracing and adopting ‘perversion’ to go against this clean and perfect idea of the Bauhaus and modern architecture and design in general. It is a way to show all the complexities, tensions, and innovations.

What do you think of the so-called ‘fourth wave’ of feminism in architectural historiography? Obviously, the media platforms on which this discussion takes place today are different than those of the mid-1990s. From the #MeToo movement, to online initiatives like the feminist wall of shame (2013), or even the Shitty Architecture Men (2018) spreadsheet, more recently.

Colomina:I very much hold the Linda Nochlin position. In her canonical essay, ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ (1971), she argues that it’s not about adding more women to the history of art history, but changing the way we look at art history. I have the same stance about architecture. In fact, if you go through the question of collaboration, then the field is full of women already. Historically, many women actually got to achieve a lot, but were left out of history. On the other hand, my work on Le Corbusier’s abuse of Eileen Gray is very much in the spirit of #MeToo and Shitty Architecture Men.

Kotsioris:Is it because the heroic figure still overshadows the ‘crowded’ reality of architectural practice?

Colomina:The heroic figure is so dominant that no one can accept the idea that there can be another kind of figure or even a kind of lack of figure, a collaborative practice, for example. Architecture has always been collaborative. Yet, somehow, certain people take all the credit. If we stop crediting only one person, you find a much more complex situation and people who get excluded. For a long time, I thought this was happening only to women, but men have also disappeared from the credits and nobody knows why. Pierre Chareau, for example, did the Maison de Verre with Bernard Bijvoet, but Chareau always, to this day, takes the credit. Bijvoet is also overshadowed by [Jan] Duiker in his earlier work in the Netherlands, the Zonnestraal Sanatorium, the Open Air School, etc. It’s all the insistence on the single figure and the unique object. This is what we have to get rid of. My favourite example is Pierre Jeanneret, half of the most famous studio of the century, without whom Le Corbusier could not be Le Corbusier, and more or less unknown.

Kotsioris:Current architectural historiography seems to be continuing with new force many of the conversations that were once intense in the late 1970s, the 1980s, or the mid-1990s. Postcolonial theory, environmentalism, gender studies, and feminism, to name a few frameworks, have carved much deeper paths in questions posed before. How do you interpret this re-emergence?

Colomina:Is it re-emergence or emergence, really? Because many of these questions were really not there before, or had a different form and meaning. It was interesting to see the first preoccupation with the environment, recycling, emergency architecture, and so on in the little magazines and the schools of architecture of the 1970s. Feminist experiments in architecture were important and present but alarmingly few. Postcolonialism was not evident at first, but decolonizing our own project, for instance, was crucial. The way we started Radical Pedagogies3 back in 2011 was in some ways naïve. Even in the exhibition we did for the Venice Biennale in 2014 (Figure 8), we were looking for experiments in architectural education in the 1960s and 1970s, and in the back of our minds were the obvious candidates: AA, Cooper Union, Ulm … the usual suspects, plus a few cases in Latin America. It was too Euro-centric. I think the project was liberated when we did the exhibition at the Warsaw Under Construction Festival. Out of it came this series of astonishing case studies behind the Iron Curtain wall, but also in Africa, Latin America, Asia, and the South Pacific. So, not postcolonialism as a theoretical position but as a lived politics of those resisting colonization. To follow up on what you were pointing to earlier about the new age of media, it has been so important to have had the online platform for the project, where so many scholars from all over the world have contributed their own research. In many ways, that has been our own re-education. Not only has the project become more global, but we have also learned how to look for and engage with situations and historical contexts that we might have not considered a few decades ago.

‘Radical Pedagogies: Action–Reaction–Interaction’, exhibit at the 14th Venice Biennale of Architecture, 2014. Curated by Beatriz Colomina, Britt Eversole, Ignacio G. Galán, Evangelos Kotsioris, Anna-Maria Meister, and Federica Vannucchi with other PhD students from the School of Architecture at Princeton University.

In the same way that architecture’s complicity with exclusion and exploitation on the basis of race, class, ethnicity, religion is at the centre of much of contemporary discourse. As an educator, do you discern a shift in the level of political alertness among students affecting these conversations? And vice versa?

Colomina:I think it is a very interesting moment. It is a re-emergence of political awareness but also a development in how we look at things (Figure 9). Every period has its own concerns and new things are coming out now. To this day I’m surprised that only very, very recently students have become activists at places like Princeton and Columbia. There have been a number of cases when this happened — whether it is slavery, the Confederate monuments, the treatment of immigrants, the #MeToo movement, and Black Lives Matter. Now, all of a sudden, there is action. But for the long time I’ve been at Princeton, I’ve always been baffled by the relative absence of activism. I find the current period very exciting for architectural history. I’m looking forward to seeing what comes out of it.

Before closing, I want to ask you about your approach to history writing, in which images seem to play a key role. At a conference on Mies you once jokingly stated that images ‘are essentially superficial. They are, first of all, surfaces. So why would I need depth?’ (Colomina 1994b: 167). How do you conceive the dynamic between text and images?

Colomina:I think in images. I cannot help it. I am like Le Corbusier, in that sense. I already start seeing the argument in images before I have written it up. Many times, the images go faster than your writing. You already have a sense of the sequence of things. I may have said that images are superficial, that they are surface, but I was just being cheeky. There’s an enormous depth to them. I spend so much time looking at them and trying to figure out what is happening there. A lot of my work consists of reading images.

Kotsioris:Where did this realization about the potential of images come from? Particularly this insistence on reading architectural images as primary sources?

Colomina:Spending time with images is something that I actually learned at Columbia, not at all in Barcelona. It was actually through Kenneth Frampton, who pays a lot of attention to images in his classes. He looks, and looks, and looks. You can look for hours and still not come up with different conclusions. But what I learned, through him, was to stay with it. You can glance at a plan and say: ‘Oh yeah, I know how this works’. But you don’t. The more you keep looking, the more you see. The crazier things you get to see. Paying attention to what was really happening there.

Kotsioris:Questions like ‘who left a fish on the kitchen counter of Villa Stein-de-Monzie at Garches?’ (Figure 10).

Interior view of the kitchen at Le Corbusier’s Villa Stein-de-Monzie in Garches, Paris, France, built between 1926 and 1928, reproduced in Privacy and Publicity (1994a: 287). Photograph by Georges Thiriet. Fondation Le Corbusier, Paris.

Exactly, who left a fish in the kitchen?! I am still intrigued by that. Or, why there appears to be somebody about to come in. Or, in what position are we placed? I stay in these spaces until I understand them. In the beginning — I don’t think that’s the case anymore — some people got the wrong idea that I was only interested in media, including photography, at the expense of the architecture. Yet, if you read closely, I’m really looking at the architectural object. That was a common misconception. When I published my book, there was such a phobia of the media. Just mentioning the word media made people cringe, as if the very thought of media dissolves the truth of architecture. But people are less nervous now, and see that media is going deeper into architecture rather than away from it. It is even to occupy architecture. It’s all about putting the figure in a picture where there are no figures, including the hidden occupant, the figure of the reader, the historian.

Kotsioris:Inhabiting the picture.

Colomina:Exactly. I inhabit the images by staying with them. Looking at the images of the houses of Loos, for instance, was a kind of occupation to me. Recently, I was back at Loos’ Villa Moller in Vienna. It was so moving to return to these spaces that I have spent so much time with in the images. At first, reading images was part of the research. It was a way to get familiar with these spaces. But eventually they are as much part of the research as the text. Likewise, they are as much part of the architect’s thinking as any drawing. I think you have to read the images with the same attention, if not more, as the text. In architectural history you cannot separate these two things anyway.

Kotsioris:With regards to text, you once said at a symposium in UCLA that Susan Sontag’s writing made you realize that you didn’t have to use the ‘pedantic language’ of historians in order to make a complex argument.

Colomina:That was the most important thing I learned at the Institute for the Humanities. Not only from Susan Sontag, but also from Wolfgang Schivelbusch and others. The pretension of architectural historians and theorists in Spain is pretty intense. The Italians are not very much better, probably worse. As a student I fought so hard to understand what they were saying, and in the end, you ask yourself: ‘Oh, is that all?’ Initially, I thought it was part of the deal and it did not come very naturally to me. In New York I realized that Carl Schorske could give a scholarly lecture and have huge audiences laughing hysterically. He would talk about Freud and people were with him and in stitches. At the Institute I realized that all these people had these very sophisticated ideas, and the true effort was how to present them in an accessible way. That’s the most important thing that one can learn from the Anglo-Saxons. Since then, being clear has become an aim to me. Laughter can be revolutionary.

Kotsioris:Any parting thoughts on history writing?

Colomina:[Long pause] That it’s hard? That it’s very difficult? The reality is that it’s hard for me to write. It’s not easy. It only flows when I get into that particular moment. But to get to that moment, I have to go through — I don’t know how many — rituals. I’m like a temperamental writer. Sometimes before I write something I can be in a terrible mood!

Kotsioris:It’s like a battle with yourself.

Colomina:It’s a battle! It’s a huge battle I have with myself every single time. The most difficult part, of course, is the beginning. I don’t know what I’ll write beforehand. I don’t keep notebooks, I only have notes here and there. I’m more of a creative writer than an academic writer. That’s the reality. I find it very difficult to write a report, or something totally bureaucratic. But if I get excited about something and get into the mood, then I find myself in this … creative space. And then I’m happy. I find myself in the flow and try to invite the reader to join me, to look and think together.

Notes

- ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) is an advocacy group that was established at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center in New York City in 1987. Its continued mission is to end the AIDS pandemic. [^]

- Carrer de la ciutat: revista de arquitectura was published between November 1977 and October 1980. [^]

- Radical Pedagogies is a collaborative research project on experiments in architectural education during the second half of the 20th century. Comprising more than one hundred case studies contributed by dozens of architecture historians and scholars from around the world, the self-titled book is edited by Beatriz Colomina, Ignacio G. Galán, Evangelos Kotsioris, and Anna-Maria Meister, and will be published by MIT Press. [^]

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Banham, R. 1996. Actual Monuments. [1988]. In: Banham, M, et al. (eds.), A Critic Writes: Essays by Reyner Banham. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 261–265.

Colomina, B. (ed.). 1992. Sexuality and Space. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Colomina, B. 1994a. Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture as Mass Media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Colomina, B. 1994b. Mies Not. In: Mertins, D (ed.), The Presence of Mies. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 167–195.

Colomina, B. 1999. Collaborations: The Private Life of Modern Architecture. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 58(3): 462–471. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/991540

Colomina, B. 2019. X-Ray Architecture. Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers.

feminist wall of shame. 2013. Available at: https://feministwall.tumblr.com/ (Last accessed: October 7, 2020).

Mulvey, L. 1975. Visual Pleasure and Narrative cinema. Screen, 16(3): 6–18. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6

Nochlin, L. 1971. Why Are There No Great Women Artists? In: Gornick, V and Moran, BK (eds.), Woman in Sexist Society: Studies in Power and Powerlessness. New York: Basic Books. pp. 344–66.

Schivelbusch, W. 1977. Geschichte der Eisenbahnreise: zur Industrialisierung von Raum und Zeit im 19. Jahrhundert. München: Hanser.

Schorske, CE. 1980. Fin-de-siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Sontag, S. 1978. Illness as Metaphor. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Tafuri, M. 1972. Teorías e Historia de la Arquitectura. Hacia una nueva concepción del espacio arquitectónico. Barcelona: Laia. (First published in Italian in 1968).

Tafuri, M. 1975a. Austromarxismo y ciudad. ‘Das Rote Wien’. Trans. Beatriz Colomina Elías and A. Llorens Geranio. Barcelona: Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Barcelona. (First published in Italian as ‘Austromarxismo e città. ‘Das rote Wien’’. Contropiano, 2(1971): 259–311).

Tafuri, M. 1975b. Socialdemocracia y ciudad en la República de Weimar. Translated by B. Colomina Elías and A. Llorens Geranio. Barcelona: Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Barcelona. (First published in Italian as ‘Socialdemocrazia e città nella Repubblica di Weimar’, Contropiano, 1(1971): 207–233).