Introduction

During the cold war era, global architectural, engineering and consulting firms benefited from the development industry through the commissions they secured from newly independent countries in the global South (de Haan 2009).1 The role these ‘global experts’ (De Dominicis and Tolic 2022; Avermaete 2010; De Raedt 2014a; De Raedt 2014b; Stanek 2020) played in the ‘theater of development’ (Levin 2022) has become increasingly central to recent architectural history research (Aggregate 2022; Silva 2020). But less attention has been paid to the political funding mechanisms that enabled and motivated Western architects, engineers and other technical advisors to cast their nets beyond their national borders during the postcolonial era. The built environments in the global South were molded not just by ‘global experts’ and organizations but also more or less directly by consulting firms in the global North that were founded for the global market and benefitted from their countries’ international trade policies. The developmentalist paradigm of the late 20th century was largely founded on the principles of economic development and modernization (Mabogunje 1980: 35–39), which created a market for consulting firms whose approaches to development relied on commercial models and pragmatic, non-idealistic methods (Doytchinov 2012) that contributed to the practical execution of developmentalist policies in the global South in the form of roads, bridges, water purification plants and industrial facilities.

To demonstrate the indirect impact of such consulting firms in the global South, I highlight the role of economic planning in the development industry. While economic planning is an essential feature of socialism (Rweyemamu 1973: 178; Rweyemamu 1972), developmentalist architectural research has tended to overlook the fact that it is a multifaceted approach that not only incorporates urban architectural practices but also rural regional ones along with social and industrial infrastructure. Taking economic planning into account brings to light the long-term dialogue between developmentalist forces and architectural state-making in the global South (Lamberg 2021). The particular rural development approach I explore in this article, namely, integrated regional development planning (IRD), has a global significance, since it was widely used in various forms of ‘spatial reorganization’ (Mabogunje 1980: 65–68) across the global South during the 1970s, following doctrinal changes in international development policy (Jacob 2018: 442–443).

I take Tanzania, commonly known as the ‘darling of the donor community’, as my point of departure. The country’s major donors from 1967 to 1975 were the US and the Nordic countries (Coulson 1982: 314–315). Following a socialist regional policy reform in 1972, Tanzania applied the IRD approach in the form of what it called the ‘regional integrated development plan’ (RIDEP) (Luanda 1998: 6), which was designed to achieve developmental goals according to the principles of ujamaa. Regional authorities were commissioned by the Tanzanian Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) to establish local planning teams supported by a variety of multidisciplinary foreign technical advisors whose mandate was to create regional five-year development plans, which attracted a great deal of developmental funding and created an influx of Western ‘experts’ in the fields of architecture and urban development, among other fields (Beeckmans 2018).2 A large number of the technical assistance teams that were invited to assist in the preparation of the RIDEPs came from the Nordic countries (Belshaw 1982: 298).

The Nordic countries’ contribution to developmentalist architectural practices was significant relative to the size of their economies (Siitonen 2005), but this contribution has not been well studied in architectural history scholarship (Berre, Geissler, and Lagae 2022). They were also active promoters of development cooperation in the UN (Siitonen 2005, 193). Their encounters with the built environments in the global South need to be understood in the context of their national development policies and in relation to the state-aid agencies in charge of executing the global outreach of the Nordic socialist democracies. Finnida, Finland’s international aid agency, was founded in 1972 as a department within the Ministry for Foreign Affairs (MFA) whose charge was to handle development policy, when the country significantly expanded its development policy (Lamberg 2021). Finnida oversaw development policy in Finland and was the most central player in managing and allocating its development funding. What makes Finland a particularly interesting case among the Nordic countries that entered the developmental business is that it sought to achieve a balance between the Eastern and Western fronts and to use aid funding to demonstrate its commitment to Western values so it could be counted as a Nordic country.

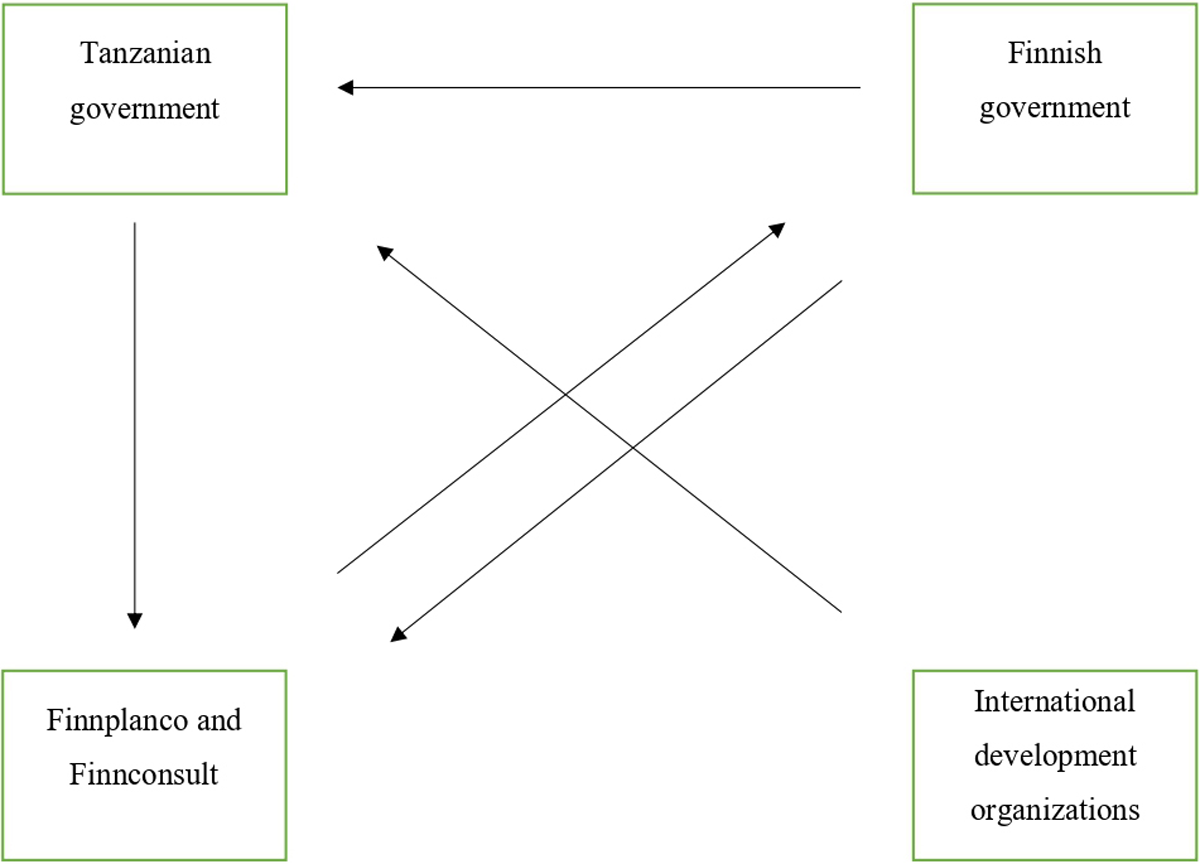

In exploring the place of economic planning in this process I look at how the three main parties to it — the Tanzanian government, the Finnish government (represented by Finnida) and the two consulting firms — used the IRD approach, closely analysing their motivations and expectations as well as the outcome of their efforts. This analysis reveals a developmentalist mechanism of profit: how the prospect of new commissions and potentially increasing the rate of return, or the so-called return flows, of development was interwoven into the IRD development model and how this motivated Finnida in its decision to fund a project that would not only help circulate Finnish experts in Tanzania but also increase domestic income in Finland.

I used two selected project reports covering the two IRD-based projects that Finnish consulting firms, Finnplanco and Finnconsult, undertook in the regions of Lindi and Mtwara, respectively, as well as the related archival documents at the archive of the MFA. Due to the outbreak of the Covid pandemic, I was not able to undertake research in Tanzania, which opens the door for supplementary research. The narrative that categorically circulates around the Western donors needs to be rewritten, a revision that Joe Nasr and Mercedes Volait’s 2003 edited volume Urbanism: Imported or Exported? instigated and that has subsequently been taken up in numerous volumes that aim to centralize non-Western modernisms (Herz, Schröder, Focketyn and Jamrozik 2015; Lu 2010; Stanek 2020). Indeed, recent contributions have challenged the hegemony of the West in defining modernism to begin with, advocating for alternative, global understandings of modernity in the context of postcolonial built environments. They highlight the active role of the agents from the global South and deconstruct the development discourse from a postcolonial standpoint (Prakash, Casciato and Coslett 2022; Aggregate 2022; Levin 2022). In signing onto the RIDEPs, Tanzania did not merely passively accept aid; rather it adopted a strategy of spreading the risks of the projects among a large number of foreign donors.

Between Multilateral Developmentalism and Ujamaa: The RIDEP Approach

IRDs dominated international developmental policy in the 1970s. In the late 1960s, international development organisations came to realise that their efforts had not really benefited the majority of people, most of whom lived in rural areas. Gradually, the major aid institutions adopted a rural approach to development, resulting in various types of poverty eradication programs (Unger 2019; Voipio 1998: 77; Havnevik 2000). In 1970, World Bank President Robert McNamara gave a speech in Nairobi in which he introduced the IRD model in the global South. The model gained wide support from other international aid organizations such as the UN Food and Agricultural Organization and the UN Development Program (Keare 2001: 159; Jacob 2018: 444; Kleemeier 1988: 61).

The poverty-oriented basic needs approach that drove development in the 1970s and early 1980s reflected what critics see as McNamara’s naive views: according to these critics, he ‘put his trust in technocracy, managerial systems, and benign authority, repeatedly underestimating the complexity, perversity, resilience, and mystery of the social systems, whether markets or political structures, that he set out to change’ (Kapur, Lewis, and Webb 1997: 220). Technoscientific approaches to national planning were seen within the development industry as particularly useful for modernization projects throughout the global South (Mehos and Moon 2011). Contemporary scholarship is quite unanimous in the opinion that these international experts failed to contribute to sustainable development and has revealed how they relied on a colonial model that inflicted epistemic violence (Koch 2020; Koch and Weingart 2016) and adopted insensitive approaches to local communities (Ferguson 1994; Hodge 2007; Mitchell 2002).

Nevertheless, the new rural development paradigm accorded with ujamaa, a form of African socialism that the Tanzanian government embraced a few years after gaining independence in 1961 and that it crystallized in the Arusha Declaration (1967). The Arusha Declaration steered the political focus to agricultural development that culminated in the concept of the ujamaa village, founded on the ideas of communal living and agriculture (Nyerere 1968). Ujamaa aimed at social equality rather than rapid industrial modernization, although achieving such equality was far more difficult than the programmatic rural development ideals insinuated it should be (Callaci 2016; Lal 2015). By early 1970s, the implementation of the ujamaa policy was characterized by the rise of state control over rural communities and food production as well as the proletarianization of the public and by the state’s ongoing collaboration with development partners to secure rural development and egalitarianism (Hydén 1980; von Freyhold 1979). During the first decade (1967–1976) after the Arusha Declaration, thousands of ujamaa villages whose purpose was to engage in collective farming were registered. This was the largest mass villagization programme that had ever been undertaken on the continent, one affecting roughly 13 million people, many of whom were forced to relocate. Ujamaa villages became embodiments of the country’s development vision (Jennings 2008: 48–49). The reform, controversially described as representative of ‘high modernism’ (Scott 1998; Schneider 2007), was a response to slower-than-anticipated development and had the effect of accelerating Tanzanian ‘statism’, resulting in the exclusion of the population from regional decision making and the fortification of the political authority of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) in the countryside (Jennings 2008: 45, 60; Schneider 2004).

Reflecting both the international development agenda pushed from outside and the internally defined ujamaa policy, the RIDEPs were critical to Tanzanian regional development goals, particularly the country’s desire for economic self-reliance (Rweyemamu 1973). By the early 1970s, the Tanzanian economy was in deep distress, and the goals of the third five-year plan (1976–1981) were tied to investment from abroad (Coulson 1982: 311). The 1972 decentralization reform emphasised regional development, and every regional directorate was expected to provide the OPM with a plan that could be integrated with the five-year plan.

The OPM expected that the RIDEPs would be crucial for Tanzania’s ability to gain further investment from abroad, as is clear from its requesting that every RIDEP should both outline a set of investment priorities and identify the key projects for each region and prepare to plan further.3 The OPM stated that the RIDEPs were primarily meant to act as operational documents in the Tanzanian government’s application for supplementary funding from the World Bank and other international development organizations: ‘The Development plan will indicate the most important development objects and projects in such a form that the plan can be used as a basis for financial negotiations with the World Bank and other bilateral agencies’.4

Originally, Tanzanian regional development strategy was divided into two stages, a planning phase and an implementation phase. Due to sporadic implementation, a second planning phase was added between 1976 and 1981 (Belshaw 1982: 298). In search of donors and collaborators for the country’s regional development projects, the Tanzanian Ministry of Finance and Planning approached a variety of state-aid agencies, or ‘friendly foreign countries’, including Finnida.5 Inviting international aid agencies to take part in regional economic planning in Tanzania was a strategic move by the Tanzanian government intended to put pressure on donors to fund subsequent projects (Coulson 1982: 314). Tanzania refused assistance ‘from countries with which it differ[ed]’ and rejected plans and proposals it considered ‘unsuitable or detrimental’ (Armstrong 1987: 265).

Finnida had funded Tanzanian development projects on a small scale since 1963, when it, along with agencies in Sweden, Denmark, and Norway, cosponsored the building of the Kibaha Education Centre in Tanzania (Berre 2022: 24–27). The Tanzanian government allotted the regions of Mtwara and Lindi to Finland, since a Finnish consulting firm, Finnwater, was already working in the area on a water master plan. After a bidding competition in Finland, Finnida chose two consulting firms, Finnplanco and Finnconsult, conglomerates made up of smaller companies that handled urban planning, construction, and infrastructure work and that supplied clients with specialized personnel for short-term projects, to serve as technical advisors to the project. These firms established multidisciplinary teams able to supply the expertise the OPM defined necessary for project implementation.6 Their planning work was conducted jointly with the regional development director’s local Tanzanian staff and supervised by the planning division of the OPM (Tanzanian Government 1975b). The two teams comprised architects, engineers, economists, agronomists and a political scientist.7

Finnida viewed international development as potentially beneficial for the Finnish economy, as it offered opportunities to grow exports, trade, and direct investment in the global South. The term ‘enlightened self-interest’, which historians believe was first used by Finnish foreign minister Ahti Karjalainen in 1967 (Kiljunen 1983: 16), highlighted the benefits of development for the ‘donor’ country as much as the ‘developing’ country: increasing employment and the balance of payments expected in Finland.

Finnida was eager to be a part of the RIDEP program because it wanted to increase its profile in the international aid industry. In March 1974 Finnida’s officials presumed that the Mtwara and Lindi regions would ‘probably need further planning assistance in the long run’ and that the project would create a continuous need for Finnish planners in the area.8 Increasing its aid efforts was a timely concern for Finnida in the early 1970s, since development policy and trade policy were starting to be seen as more related. A 1974 report prepared by the Committee for Diplomatic Service (a governmental agency that oversaw foreign policy) estimated that the significance of the ‘developing countries’ for Finnish trade policy was bound to grow in the following years (Ulkoasiainhallintokomitean 1974:n mietintö 1975: 49–50). Furthermore, the report pointed out that ‘the planning and decision making in development policy, trade policy and the diplomatic service in general must be considered intrinsically interconnected’ (55, my translation). A 1974 governmental position paper concerning Finnish development policy made a similar argument: ‘Development policy and trade policy are affiliated with one another and therefore they should also be in concordance with one another’ (Kansainvälisen kehitysyhteistyön periaateohjelma 1974: 3, my translation). Finnish aid contracts thus emphasized using a Finnish workforce and Finnish resources (such as equipment or materials). Aid was therefore more ‘tied’ to the economy in Finland than it was in the other Nordic countries (Kansainvälisen kehitysyhteistyön periaateohjelma 1974: 13–15; Forss et al. 1988).

Regional economic planning was seen by the Finnish foreign policy officials as not just economically but also politically profitable. In the 1970s, Finland sought to associate itself with the ‘neutral’ Nordic cluster. Becoming a member of the ‘donor’ pool was a strategic choice that helped Finland gain credibility as a neutral country that could serve as a mediator between the West and its neighbor, the Soviet Union (Siitonen 2005: 180–195). Development cooperation was central to the foreign political agenda of the Nordic countries, including Finland (Kehitysyhteistyön vuosikertomus 1980: 7–8). Commenting on regional planning projects in 1974, Martti Ahtisaari, Finnish ambassador in Dar es Salaam in the 1970s and future president of Finland, stated that concentration on the national as well as regional level was useful for the ‘image’ of Finnish development cooperation and therefore also Finland, since it would make Finnida’s efforts internationally more visible. Therefore, he advised that Finnida prepare itself for follow-up contracts in the area.9

While the Nordic countries played a large role in the first planning stage, the implementation phase was mostly undertaken by the so-called multilateral aid agencies. The second planning stage, in turn, speaks volumes about the inefficacy of the RIDEPs: only a year after Finnplanco and Finnconsult completed their regional economic plans, they were replaced. The World Bank ultimately turned out to be the most committed donor and implementor of the rural developmental policy of its own making in Tanzania. The developmental alliance between socialist Tanzania and the capitalist World Bank resulted in five regional plans in the Kigoma, Tabora, Mwanza, Shinyanga and Mara regions that were prepared by the World Bank’s sister organization, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (Belshaw 1982: 298). The Kigoma plan was finished early and then became the model for the rest of the RIDEPs, serving as the ‘blueprint’ for rural development (Payer 1983: 794; Jacob, 2018; Launonen and Ojanperä 1986, 75). Fostering the relationship with the World Bank turned out to be a profitable strategy for Tanzania, as the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development subsequently invested in the implementation of all five of their preliminary plans.

From Rural Hinterlands to Productive Economic Regions: Two Approaches

In line with the ujamaa policy, the RIDEPs were designed to fight rapid, informal urbanization and to promote more inclusive and even economic development at the regional level in particular, by supporting communal living and agriculture that would reduce migration to cities. The strategic distribution of investment, the strategic placement of infrastructure and industry, and the expected modernization of rural areas were intended to foster a connection between social and spatial equity (Tanzanian Government 1975a). According to the Tanzanian OPM’s guidelines handed out to all donors, the ideal economic plan would promote economic development, foster social cohesion, and make possible the realization of ideological goals:

A well-prepared integrated development plan would facilitate rational allocation of the limited resources in a Region and eliminate possible wasteful use of scarce resources. This would also ensure participation of a large number of people as the only sure way of extending investment opportunities to the masses at grassroots level. By concentrating development resources in the critical sectors the rural-urban income disparity would be narrowed faster than is the case presently, and greatly contribute towards the development of Tanzanian socialism and self-reliance.10

The consulting firms’ work in Tanzania yielded two project reports, Finnplanco’s Lindi Region: Integrated Development Plan for 1975/76–1979/80 and Finnconsult’s Mtwara Regional Integrated Development Plan, 1975–1980, each of which describe very different means of achieving the project guidelines. In order to understand the nature of the projects, it is important to know that after the planning exercise phase Finnplanco and Finnconsult did not proceed to the implementation phase, meaning that the plans under analysis existed on paper only. The reports also cover a lot of territory. The Mtwara project report, for example, is divided into three sections: the first offers an ‘organized source of information’ for policy planning and decision makers; the second compiles basic regional facts such as population and the extent of water supply; and the third outlines the strategic goal-setting agenda of Tanzanian development (Tanzanian Government 1975b, 6). The Mtwara and Lindi plans should thus be understood primarily as economic plans (Porvali 1995: 204) that present ‘an organized collection of different projects … considered reasonably realisable during the [five-year] plan period’ (Tanzanian Government 1975b, 6). Nevertheless, the economic planning aspect had many implications for the social and spatial development of the rural areas. Investing in rural areas that sought to effect the ujamaa policy meant also addressing the need for the development of roads, schools and health centers, among other things.

Both Mtwara and Lindi were considered rural hinterlands that had little connection to the larger cities and were practically outside of the reach of the Tanzanian government (Lal 2015: 142–155; Mesaki and Mwankusye 1998). That Mtwara was, as Priya Lal puts it, a ‘dormant, static and isolated’ (2015: 142) region did not dampen Finnida’s interest in the project. Rather it did quite the opposite: Finnida justified the focus on Mtwara by noting that it comprised a separate economic zone with distinct regional boundaries that made change possible on a small scale, regardless of what was happening at the national level.11 Concentrating development resources in critical sectors and regions seemed like a quick way to facilitate regional economic equality.12 Tanzanian developmental strategy sought to transform Mtwara and Lindi by closely connecting them with the international development industry.13

Self-Sufficient Food Production and Cash Crops

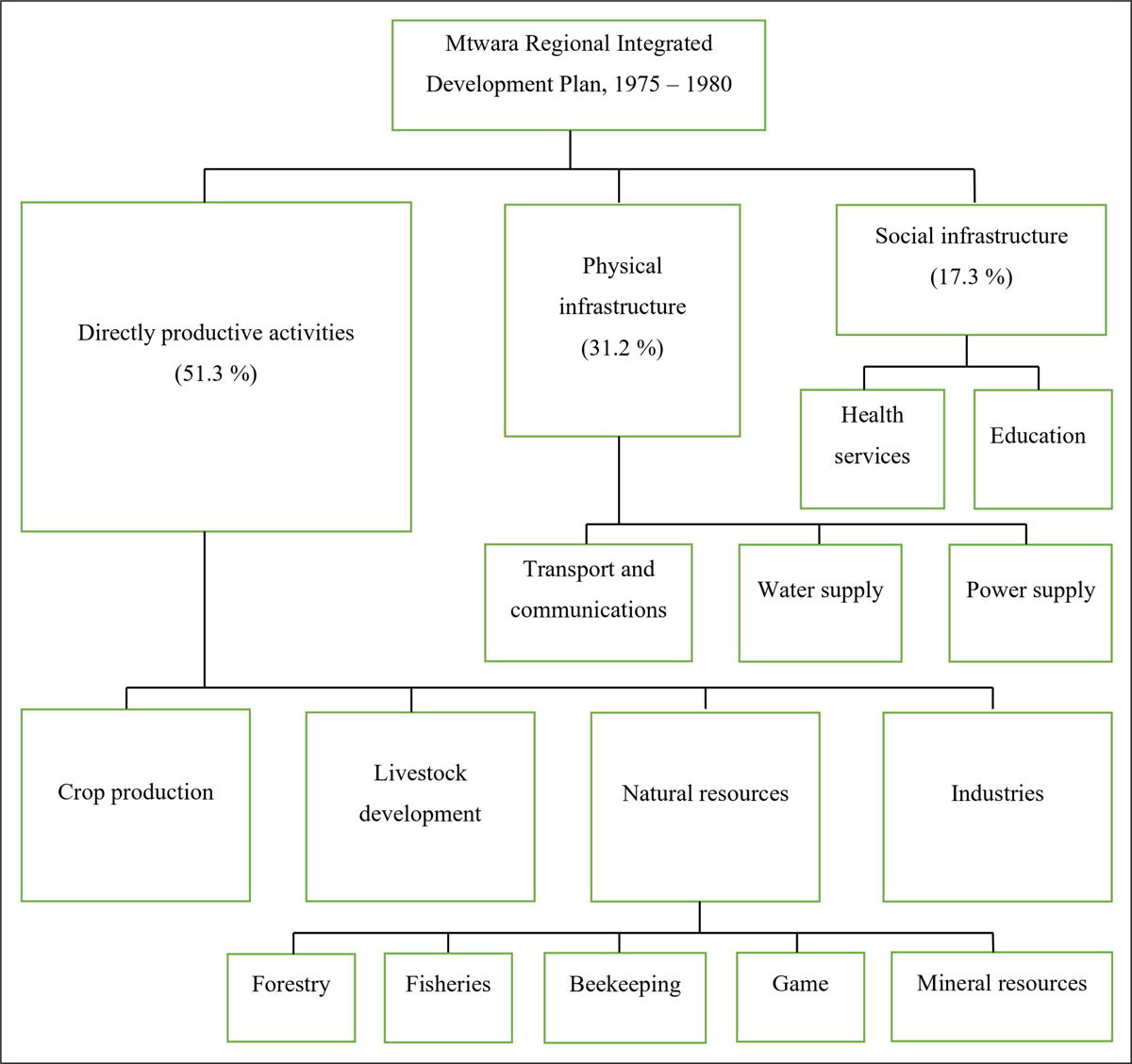

In Mtwara, the Finnconsult team noted that regional malnutrition was the most pressing issue. By concentrating on ‘directly productive activities’ (Figure 1) the team’s intention was to increase the amount of cultivated land (which was less than 10 percent at the beginning of the project) so as to elevate the nutrition level in the region and enable it to achieve self-sufficiency in food production by 1980. Expanding the amount of cultivated land would be made possible by increasing regional processing capacity (Tanzanian Government 1975b, 35). The economic development model in Mtwara relied on increasing the cultivation of cash crops, the most important of which was the cashew nut.14 The approach was quite simple and pragmatic. Because the planners shied away from projects requiring significant funds, sectors such as education were only given a small budget.

The report explains that building a road system and expanding water supply were critical to increasing agricultural output. On the matter of water supply, Finnconsult collaborated with a Finnish consulting engineering firm, Finnwater, which had been working to establish a water master plan in Mtwara since 1974 (Tanzanian Government 1975b, 100). The report then proceeds to a discussion of social aspects, emphasizing the need for more educational facilities and health services. Adult education, the report suggests, should promote self-reliance and thus rely on domestic science centers, handicraft centers and agricultural centers, to name a few, which would help boost labor intensive work in the region that depended on local production and local materials (Tanzanian Government 1975b, 9).

In September 1974, Henrik Westman, head of Finnida at the time, reported that Finnplanco and Finnconsult had reviewed the World Bank’s planning documents for a loan it was about to give Tanzania primarily to develop its cashew nut production in the southern regions, namely, Mtwara and Lindi, but also to support certain social and physical needs.15 The fact that the two firms were given access to these documents shines a light on the commercial operating mechanisms of global consulting firms in the development industry and indicates how a chain of commissions was forged alongside developmental policies such as the IRD approach.

A Prelude to Technoscientific Modernization

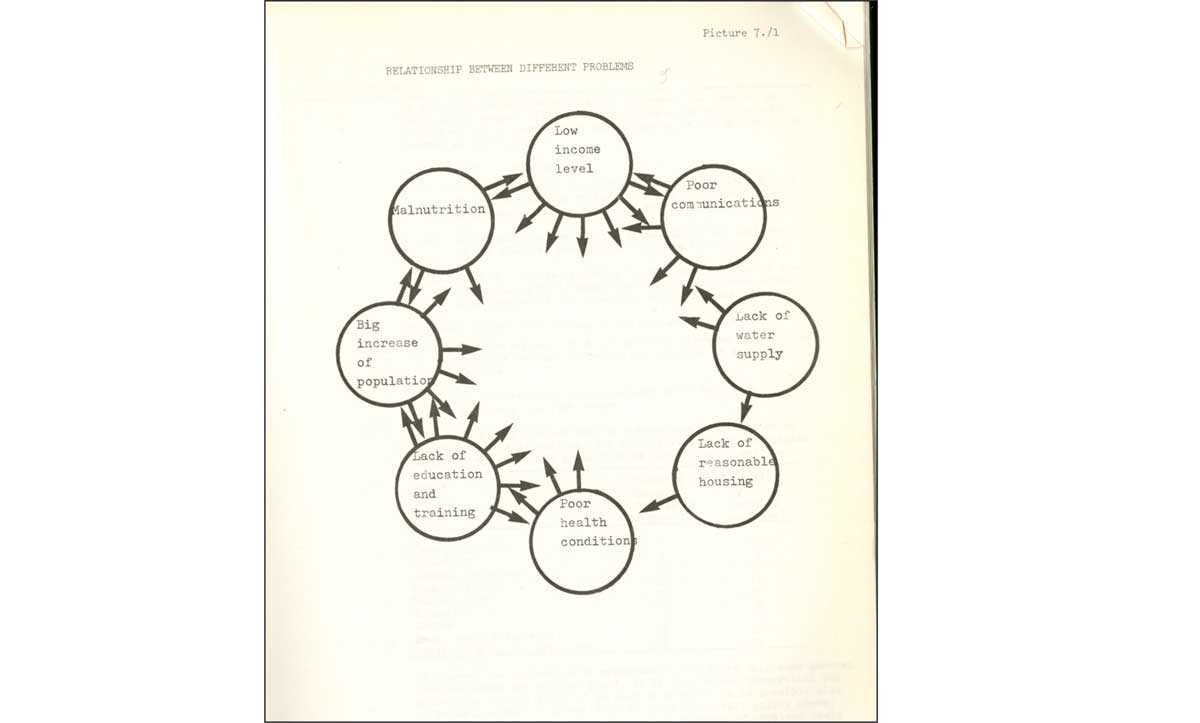

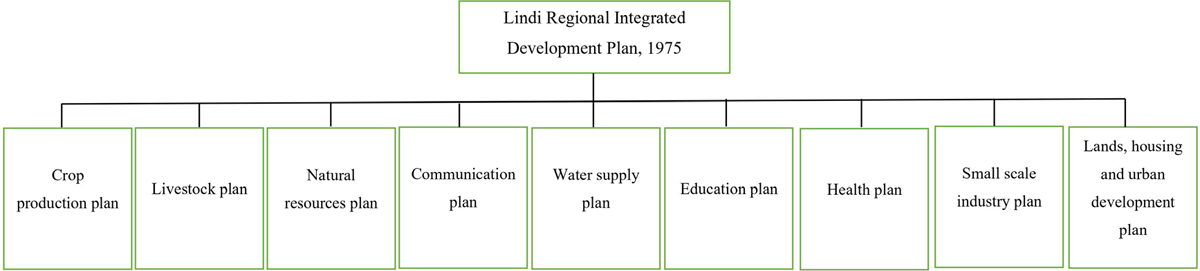

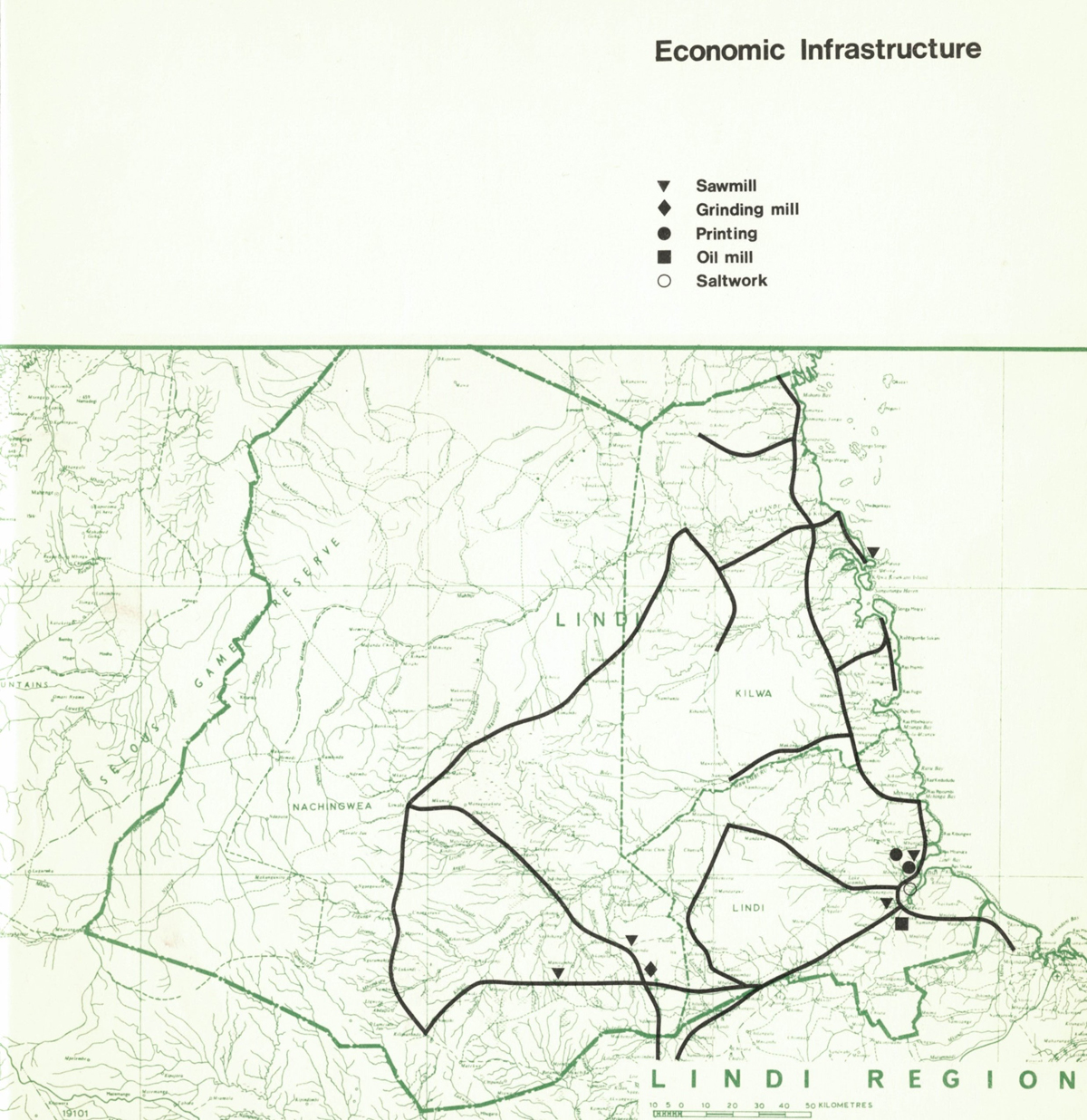

The Finnplanco team in Lindi took a more problem-based approach to regional development than Mtwara’s team (Figure 2). But whereas the Mtwara team worked out a coherent, realizable development approach, the Lindi team took a more technoscientific approach. The Lindi plan was divided into nine hierarchical sectoral plans (Figure 3) that were not integrated with each other, even though this was a requirement for RIDEPs.

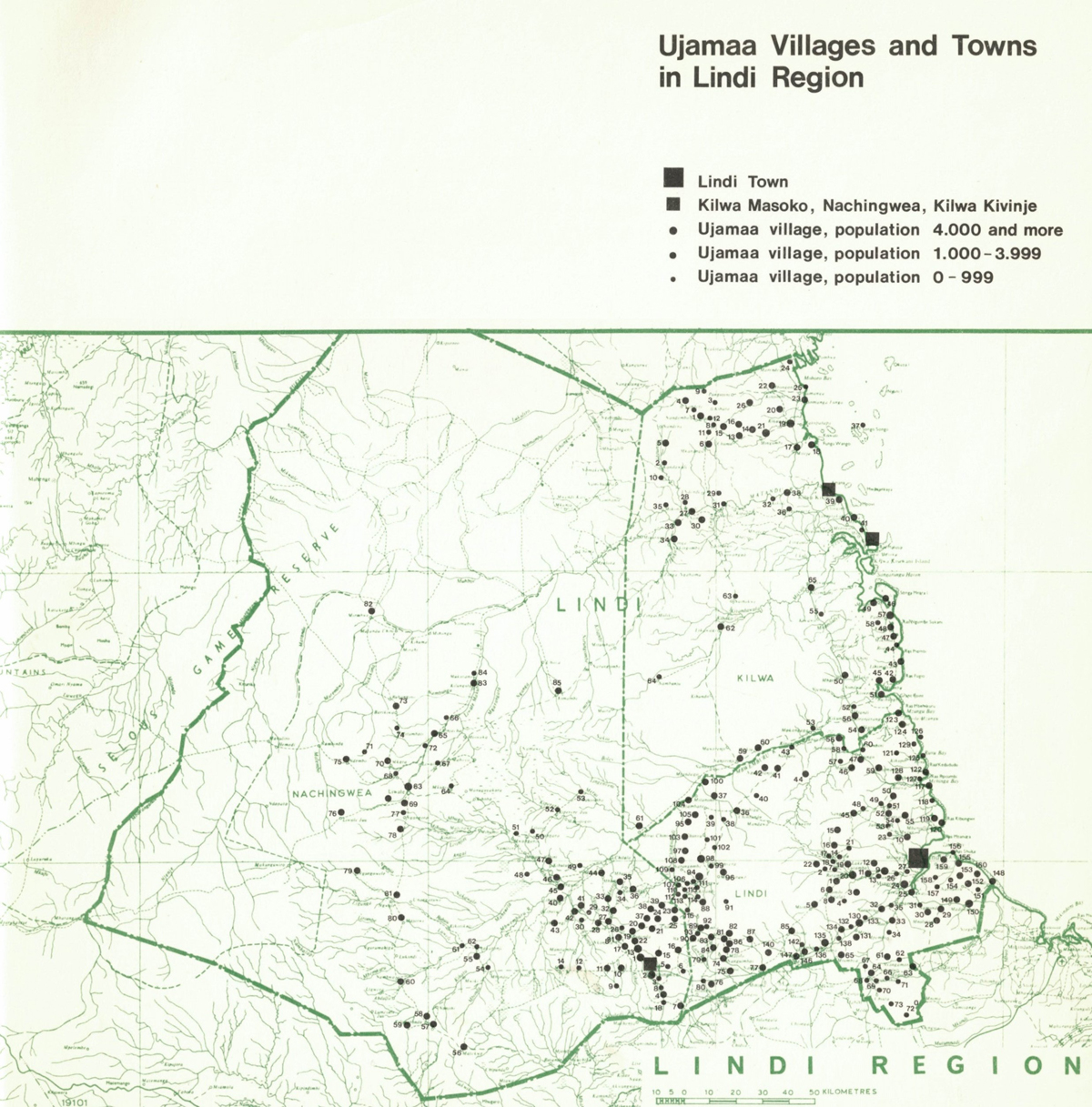

Next, I will demonstrate how the RIDEPs were expected to serve as stepping stones for subsequent commissions by examining Finnplanco’s third sectoral plan pertaining to lands, housing and urban development. This sectoral plan covered two main categories: the ujamaa village and the three towns of Lindi Town, Kilwa Masoko and Nachingwea. The most pressing issue was the relationship between the ujamaa villagization program, which was going strong, with the entire population expected to live in these villages by the end of 1975, to economic development (Figures 4 and 5) (Tanzanian Government 1975a, 412). Finnplanco’s approach to villagization was quite simple: on its plan, by 1980, every village would be demarcated and provided with a land use survey through which it would identify the most suitable land for crop cultivation (Tanzanian Government 1975a, 421). The plan therefore presumed that the regional development work would be fleshed out in later stages, making it a preparatory phase.

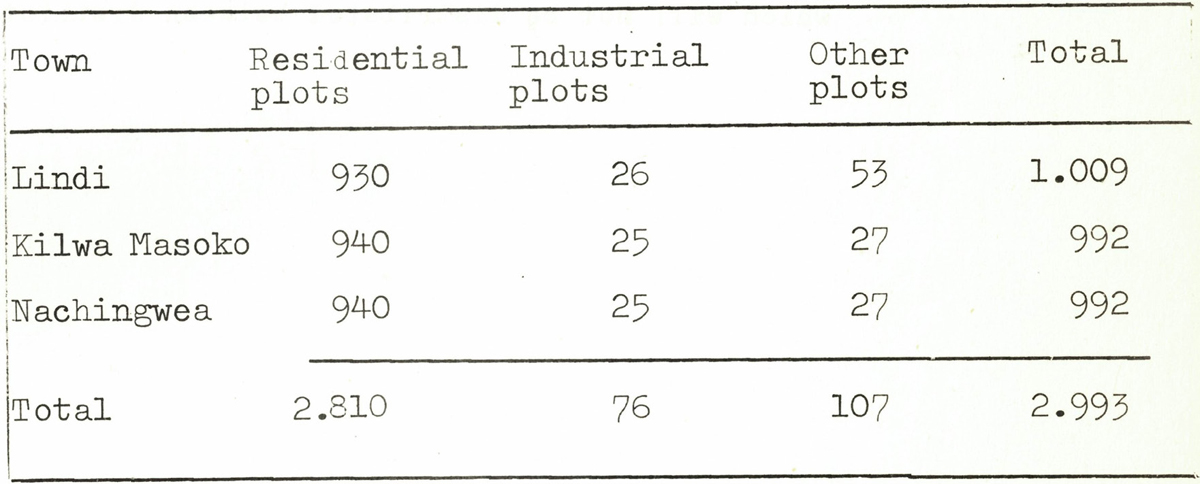

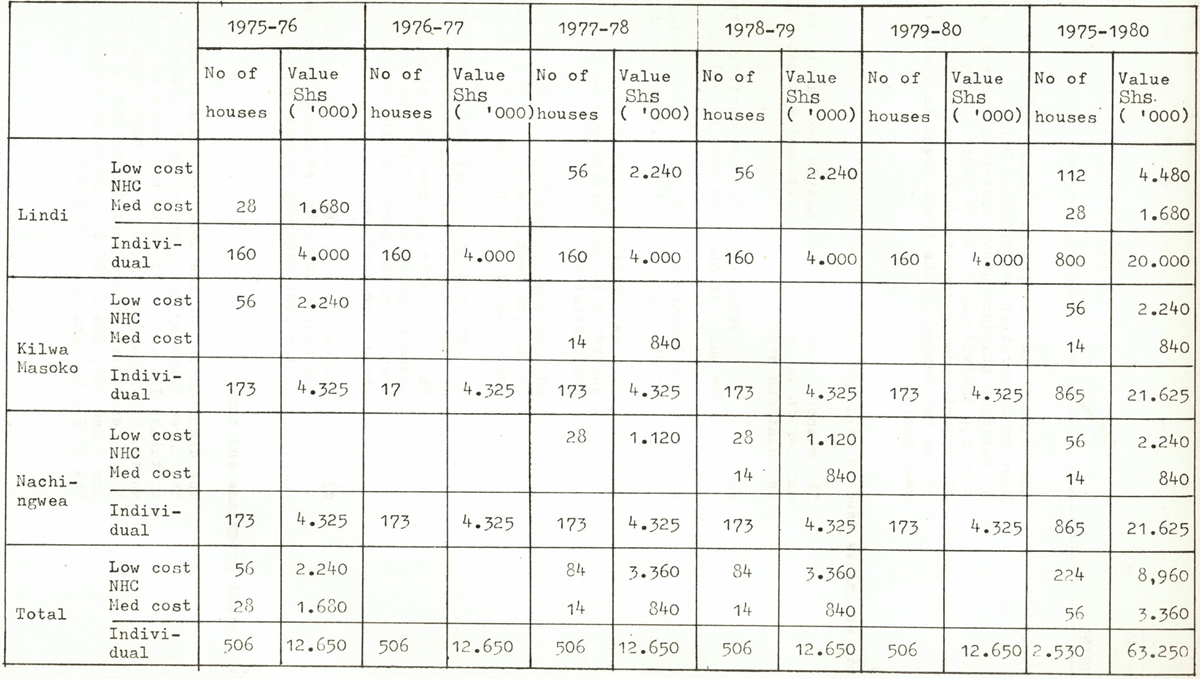

Finnplanco outlined three main ways to develop the towns in the region: by implementing ‘sites and services’ programs, providing the towns with urban infrastructure and increasing house production. The goal was to decrease the percentage of the urban population living in ‘unserviced and unsurveyed’ areas from 45 to 32 by 1980 (Tanzanian Government 1975a, 418–419). Site clearance and surveying for new plots in the towns were ‘the first activities’ to be undertaken to ‘improve urban conditions’ (Tanzanian Government 1975a, 425). Out of a total of 2,993 new plots Finnplanco proposed across the three towns, most were envisioned as being residential, the goal being to alleviate the effects of ‘informal’ urban development (Figure 6).16 After the plots were cleared, according to Finnplanco’s plan, urban development would continue with the provision of infrastructural services such as water, roads, electricity and sewage. The report states that ‘urban economic infrastructure is quite expensive, but it is inevitable if the towns continue to exist and develop,’ thus hinting that more outside investment would be required for this plan to be implemented (Tanzanian Government 1975a, 431). Housing would, according to the plan, be built partially by the National Housing Corporation (280 units) and partially by the residents themselves (2,510 units) in the five-year period (Figure 7), at a cost of the hefty sum of 63,250,000 Tanzanian shillings (Tanzanian Government 1975a, 437). In addition, the report points out that Lindi suffered from a lack of ‘adequate survey equipment’, ‘adequate transport facilities’ and ‘sufficient manpower in surveying and town planning’, therefore once again indicating a growing need for assistance from abroad, a problem the report fails to (or chooses not to) address (Tanzanian Government 1975a, 416).

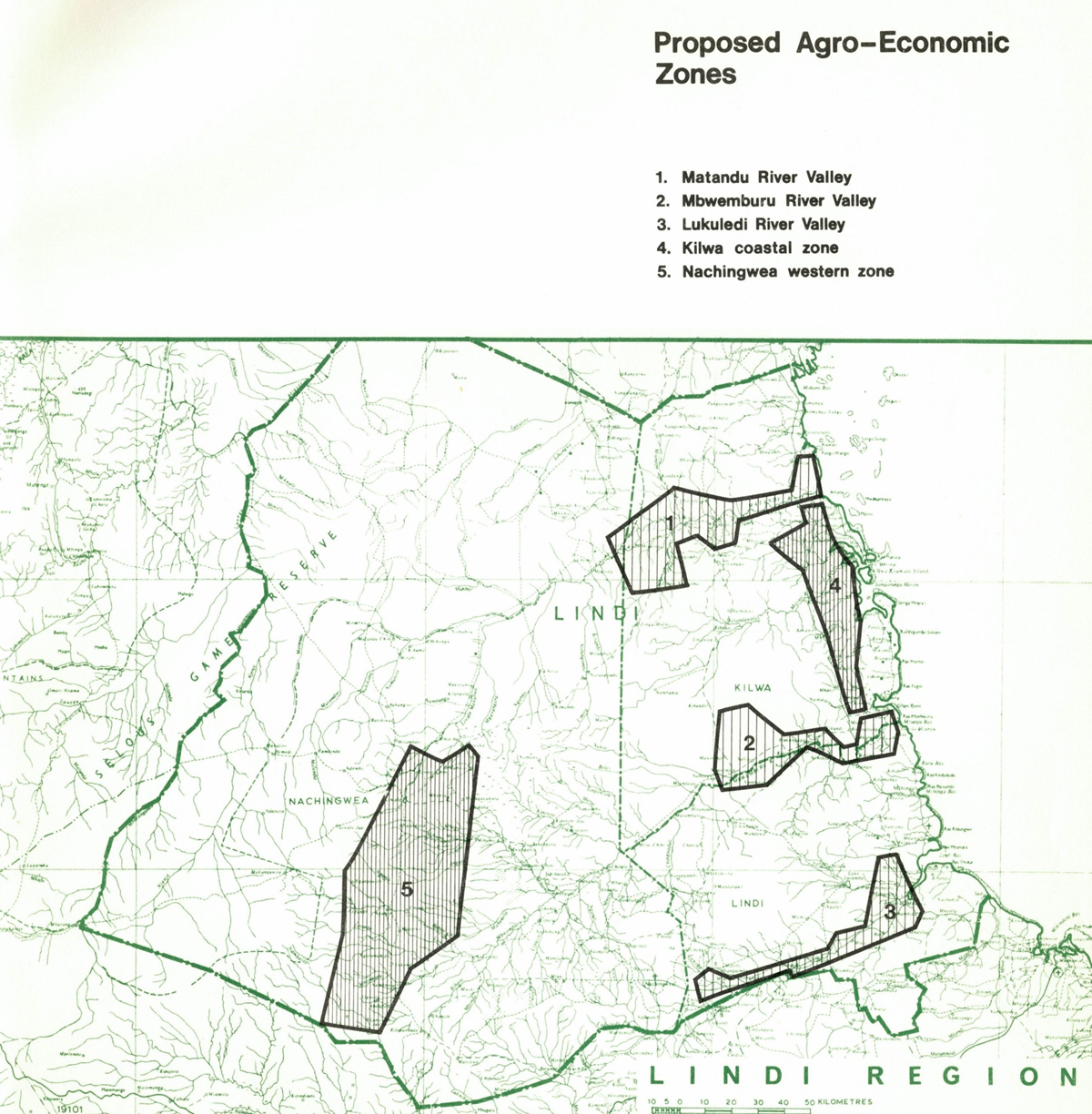

The closest the Lindi team came to providing a practical development plan was when it proposed that the region establish new agroeconomic zones mainly based on soil fertility (Figure 8). Without developing this idea further, the report recommends that ‘more detailed surveys and agroeconomic studies … be made for the development of the zones’, which underlines the extent to which the report relies on the idea that social and economic development in Lindi necessitated increasing dependency on foreign assistance (Tanzanian Government 1975a, 74).

The key difference between the Mtwara and Lindi RIDEPs is that the Mtwara RIDEP emphasized the principle of self-reliance. Exhibiting a greater awareness of the scarce resources available for development than the Lindi plan, the Mtwara plan called for increasing local, labor-intensive production, utilizing knowledge production, and concentrating the development efforts on a few key programs that would benefit the majority of people, such as agricultural development, as requested by the OPM, and did not require the ambitious investment the Lindi one did (Tanzanian Government 1975b, 35). For example, the cost of the proposed lands and housing development in the Mtwara plan amounted to 1,878,500 Tanzanian shillings compared to Lindi’s 63,250,000 (Tanzanian Government 1975b, 4). The Mtwara team also emphasized the open-ended nature of the plan, noting that it would need to be repeatedly reassessed in light of the ever-changing conditions in Mtwara (Tanzanian Government 1975b, 6–8).

The Lindi team in contrast adopted an idealistic, politically motivated development language that derived from a technoscientific mindset while relying on the premise of huge foreign investment and ever-growing contributions from ‘global experts’. The technocratic model applied in Lindi reflects Cold War techno-politics that sought opportunities for circulating experts and underscored the idea of portable knowledge (Dargent 2014; Mack 2019; Putri 2020; Sedighi 2018; Chastain and Lorek 2020). The Lindi team’s proposed development model recalls the model most familiar to the planners: the Nordic welfare state, which was compatible with ujamaa principles in a way but was simultaneously too expensive of a development model to promote in an agricultural economy like Tanzania. Both plans were subsequently criticized by the British for paying too much attention to social welfare and not enough to production (Voipio 1998: 94).

‘A Basketfull of Project Ideas’

In addition to being understood as economic plans, the RIDEPs functioned as ‘basketfull[s] of project ideas’, which is how they were described in a letter from the OPM to regional development directors outlining their goals and key indicators.17 By November 1974, the two teams’ work had been surveyed by T. Rutamigva, an OPM representative, and J. S. Nnunduma, a representative of the Ministry of Finance. Together with personnel from the Finnish embassy and the two advisory teams, they drafted a list of follow-up projects for future collaboration in the regions. The follow-up projects were later integrated with the development projects that were to be implemented after the first planning phase was completed. For example, to boost the most important development sector, crop production, in Mtwara they proposed creating a maize program, a paddy program, and an oilseed program, enlarging state farms, instituting dry season farming and irrigation, developing horticultural units, setting up a seed multiplication farm, building an agro-mechanization center, improving of extension services, and finally fostering cashew nut production (Tanzanian Government 1975b, 39–40). As long as the list is, crop production is just one of many sectors addressed in the RIDEP, all of which are accompanied by a similar list of suggested development projects. The funding of the ‘basketfull of ideas’ was expected to come from the international aid community.18 The Tanzanian government was hoping that the funder of the two RIDEPs would be Finnida. Finnida, however, had never envisioned covering the cost of the entire implementation phase but hoped to attract multilateral interest in the project.

It is important to understand that the RIDEPs were fundamentally instrumental in nature: the regional plans as well as the follow-up projects were vital to the creation of developmentalist interdependencies among the Tanzanian government, the two consulting firms, and Finnida. Finnplanco project manager Jaakko Salonen’s account of his two-week excursion to Tanzania is particularly revealing in this context: he described how he promoted the firm ‘all over the (Finnish) Embassy’ and socialized with a great number of Finns working in Tanzania to pick their brains for promising business ventures in the country. His discussions prompted him to propose a list of potential follow-up projects not just for the Lindi region, which was the task, but for the whole country. These ideas ranged from drafting general and land-use plans to undertaking physical planning practices in ujamaa villages.19 It was not just the Finns who used the RIDEPs as stepping stones for further development investment in the country but the Tanzanians too, who took an optimistic approach in state development. Salonen suggests that this optimism resulted in the Tanzanian government devising overly ambitious and utopian visions that he saw as ultimately unrealistic.20 The Mtwara team’s suggested proposal for follow-up projects was more down-to-earth than the Lindi team’s in its emphasis on supporting the goal of self-reliance in Tanzania. The Lindi team’s potential follow-up projects depended on bringing a huge foreign workforce into the country.

Motivations, Expectations, Outcomes

The main beneficiaries of the project were the global experts (Table 1). Had the RIDEPs proceeded to implementation with multilateral funding and Finnish contracting as envisioned by Finnida, Finnplanco and Finnconsult, the financial gain would have been significant for both the Finnish companies and the Finnish government. My analysis suggests that Finnplanco and Finnconsult were not really trying to make themselves useless by supplying technical assistance to Tanzania, which is the standard justification for developmental interventions. On the contrary, with the help and approval of Finnida, they actively attempted to launch operations that would require their ongoing presence in Mtwara and Lindi and to promote a business model that would make them indispensable to the newly independent developmentalist states. That being said, the RIDEP proposed by the Mtwara team was in many ways more practical, took into account the scarce regional resources, and provided the developmentalist tool that was called for by the Tanzanian OPM, unlike Lindi’s team. It is probable that global funders such as the World Bank would have preferred Mtwara’s approach as well.

Motivations and Expectations of the Tanzanian Government, the Finnish Government and the Two Consulting Firms with Respect to the RIDEPs and the Outcomes of the Plans.

| Motivations | Expectations | Outcomes | |

| Tanzanian government | Ujamaa | Stronger socialist state; rural social and economic development | None |

| Finnish government | Increase the ‘return flow’ of development aid; build an image of ‘Nordicness’ | Stronger export base | Negative evaluations and a change of heart |

| Consultancy firms | Integration with the development industry | An ongoing chain of commissions in Tanzania | Lessons learned and growing involvement in the development industry |

For the Tanzanian government the project was a dead-end. A 1995 assessment summarizes criticisms regarding the general IRD approach, noting the failure to practice bottom-up planning, the failure to integrate the project with existing institutions, poor project management, the rigidity of the so-called blueprint planning, the lack of commitment on the part of project collaborators, and abbreviated implementation periods (Porvali 1995: 204), which accurately describes particularly the Lindi team’s approach. Research on technical assistance in Tanzania provides insight into why the RIDEPs did not work as planned. Joseph Semboja’s and Ole Therkildsen’s (1994) work, for example, suggests that projects intended to increase regional equality in fact undermined popular participation in the regions because they had the effect of dissolving local, pre-1972, government systems. In his analysis of the master plan prepared for Moshi, Tumsifu Jonas Nnkya arrives at similar conclusions (2008). According to Nnkya, planning should not have been the sole province of the Tanzanian one-party elite and foreign planning teams but should have included residents.

That the Mtwara RIDEP adopted a different approach from the Lindi RIDEP did not matter when it came to results. Unto Korhonen, the MFA’s deputy head of department at the time, predicted that the failure to work out a way to practically collaborate with local Tanzanian institutions would result in the final reports ‘collecting dust on a shelf somewhere’, which is indeed exactly what happened.21 After the planning phase Finnida backed out of further investment in the regions due to the hefty price tag, as did most other donor organizations. Their decision was influenced by the lukewarm evaluation of the RIDEPs commissioned by Finnida in 1982 and the negative remarks in a research report written by Lizz Kleemeier, who was affiliated with the Political Science Department of the University of Dar es Salaam at the time.22 The Finnish embassy in Dar es Salaam had forwarded Kleemeier’s report to Finnida to caution Finnida against further involvement.23 Regional planning, according to Kleemeier’s report, had become a political tool through which the Tanzanian government sought to gain control over the countryside by replacing local social systems with TANU’s administrative units.24

Kleemeier also describes the destructive development mechanisms in Tanzanian regional planning. She argues that donors generally ignored Tanzania’s economic and political situation, the result of which was weak plans. According to her, the belief that ‘foreign capital, administrative organization, and ideology could centralize sufficient power in the state for it to push forward with the preferred development model’ informed the OPM’s guidelines.25 However, ‘no donor alone,’ she remarks, ‘would have been able to finance all of a RIDEP, as most of them were quite large and ambitious. Nor were many donors interested in picking up the tab for projects designed by another donor.’26 Indeed, it is clear that Finnida never intended to fund the implementation phase in full but instead wanted to create an economic relationship between Finnish companies and the international development industry.

The forging of new economic dependencies motivated economic planning within the development industry, as private consulting firms in the global North saw it as having profit potential. Both the Tanzanian government and the Finnish companies were at the receiving end in this industry, while multilateral development organizations were at the giving end, holding the power to allocate significant funding to projects that convincingly followed the developmental agenda set by the main donors. Finnida actively lobbied the development industry in the hopes of increasing the influx of tax revenue that Finnish companies successful in the global contest for building contracts would pay to the government. Figure 9 shows how economic planning became a means through which the Tanzanian OPM, Finnida, and the two private companies wove a web of economic interdependencies and how all of them actively strived to secure a funding relationship with multilateral developmental organizations using their own specific methods. The Tanzanian government adopted the development paradigm that fit with the ujamaa policy that had guided Tanzanian socialism since 1967 and used it to strengthen its relationship with the main advocate of the IRD approach, the World Bank. Finnida took a nationalistic approach to development and tried to establish Mtwara and Lindi as satellite stations of Finnish fiscal policy. Finnplanco and Finnconsult tried their best to make themselves irreplaceable and sought to establish a new source of contracts for their engineering services in Tanzania to compensate for a slowdown in Finnish contracts owing to the country’s declining construction market. This situation recalls the former colonies’ structural dependence on metropolitan capitalism during and after colonialism that Tanzanian scholar Justinian Rweyemamu (1969, 1971, 1973) identifies as the main reason for underdevelopment in Tanzania (see also Okoko 1987: 226–228). The IRD approach resulted in the parceling of Tanzania into ‘donor agencies’ small “colonies”’ (Luanda 1998: 6). The regional development project was thus truly cooperational only for the Finnish government and Finnplanco and Finnconsult.

Developmentalist Interdependencies: The Projected Funding Mechanisms, Indicated by Arrows, of the IRD Approach in Mtwara and Lindi, 1975–1980. Source: author.

Even though the RIDEPs were not as profitable as Finnplanco and Finnconsult had hoped they would be, the Finnish consulting firms’ global conquest had only just begun. During the 1970s, the commercialization of Finnish development gradually increased, although it stayed well below the OECD average level of commercialization in other donor countries (Kiljunen 1983: 24). The 1980s are considered the heyday of development-oriented consulting firms, whose export efforts were successful in other areas such as North Africa and the Middle East (White 2020; Lamberg 2023). On the African continent, Finnida teamed up with Finnish companies up until the 1980s, when the planning and construction market in sub-Saharan Africa began to shrink (Laakso and Tamminen 2014: 250). The so-called structural adjustment programs forced on Tanzania by international financial institutions cut public investment in the country and led the Tanzanian government to adopt an economic privatization and liberalization model in the period from 1982 to 1987 (Luanda 1998: 4; Kilindo, Mjema and Msambichaka 1995.).

The commercialization of development continued in Finland. Arrangements such as export promotion through grants and credits and the establishment of a special fund for industrial development cooperation (Finnfund) in 1980 were intended to stimulate direct investments and industrial cooperation in the global South. This coincided with the rise of development projects in the fields of engineering in the 1970s and 1980s that employed a growing number of consultants in technical fields. A 1988 study found that Finnish technical assistance projects utilized a relatively larger number of consulting-based approaches to development compared to other Nordic countries (Forss et al. 1988). These efforts finally paid off. By the 1980s, the rate of return for Finnish aid was around 60 percent of total aid (Kiljunen 1983: 16–25; Koponen 1998: 16–20). The industry, mining and construction aid subsector — the subsector category into which most of the Mtwara and Lindi regional economic plans fell — comprised only 2.4 per cent of all bilateral official development aid in 1973, but by 1980 it made up 41.4 percent (Kiljunen 1983: 64). This indicates that the Mtwara and Lindi projects were conceived at a critical time and contributed to the later success of the Finnish consulting firms in the form of a sort of a ‘lessons learned’ experience.

Conclusion

RIDEP funding patterns suggest that the Tanzanian government successfully used the multilateral development agencies’ own dominant developmentalist language and policy making models as a tool to bring more development funding to Tanzania. Such investment must have had an effect on settlement patterns and environments. Still, the significance of the IRD approach to Tanzanian settlements and livelihoods remains unclear, and few research articles (this one included) have been able to assess the exact impact of such grand visions for those outside the group of ‘global experts’ or political elites. Lal (2015) notes that the ujamaa experiment, regardless of the failings that have been pointed out in scholarship, remains integral to this day to everyday life in rural communities. Additional research is needed to understand how such grandiose schemes as the IRD approach were viewed locally and how they shaped lived experience.

Exploring developmentalist white elephants and unfinished projects fills in the gaps left by architectural scholarship that generally focuses on the completed, physical forms of architectural practice. Analysing the IRD approach from the perspective of architectural history reveals the mechanisms through which ‘global experts’ created economic plans for the global South that were designed on the premise of the ongoing presence of foreign experts, therefore fortifying the economic dependency stemming from colonial times. The analysis shows how the relationship between ‘global experts’ and the development industry was founded on the dogma of modernization, which the case of the regional development of Mtwara and Lindi exemplifies. After the Finns had chosen to withdraw from the implementation phase, another similar project was undertaken just a year later by United Kingdom Overseas Development Administration (Belshaw 1982: 298; Launonen and Ojanperä 1986: 92). A bit surprisingly, in 1988, the Finns renewed their interest in rural development in the area and launched another poverty eradication program, or ‘a new kind of IRDP’ (Voipio 1998: 89), called RIPS (rural integrated project support), which ended in 2005, thus bringing to an end a 30-year presence of Finnish technical advisors in the area. Analysing the significance of the IRD approach to architectural history demonstrates that it is not enough to only consider the concrete outcomes and urban manifestations of architectural globalization. Similar attention should also be paid to the long-term policy making impact that architectural players, such as consulting firms or ‘global experts’, have had on the developmentalist models that define human environments today.

Notes

- These companies include Doxiadis Associates (Bromley 2023; Tolić 2022; Phokaides 2018), the ‘Second World’ companies such as Technoexportstroy, Romconsult, and Miastoproject (Doytchinov 2012; Vais 2012; Stanek 2012), KPDV (De Raedt 2014a) and Norconsult (De Raedt 2022). [^]

- OPM, ‘Guidelines on Technical Assistance for Increasing Planning and Control Capacity of Regions’, AMFA/12R/ML. [^]

- OPM to regional development directors, 23 May 1974, AMFA/12R/ML. [^]

- Preliminary plan of operation in Lindi, attachment to the contract between Finnplanco and the MFA, 13 June 1974, AMFA/12R/ML; minutes of the meeting of Finnish project management, 18 February 1975, AMFA, 12R, ML. [^]

- Minutes of the regional team meeting held in Mtwara, 30 July 1974, AMFA/12R/ML. [^]

- The Finnplanco team in Lindi consisted of representatives from Insinööritoimisto Granlund-Oksanen, Insinööritoimisto K. Hansen & Co, Oy Kaupunkisuunnittelu Ab, Km Insinööritoimisto Oy and Suunnittelukonsultit Oy (Finnplanco tender document, 16 April 1974, AMFA/12R/ML). The Finnconsult team in Mtwara consisted of representatives from Placenter Ltd (Suunnittelukeskus Oy), Vesi-Hydro Ltd and Viatek Ltd (Finnconsult tender document, 16 April 1974, AMFA/12R/ML). [^]

- CVs in Finnplanco tender document, 16 April 1974, AMFA/12R/ML, Viatek’s info sheet, attachment to Finnconsult tender document, 16 April 1974, AMFA/12R/ML; CVs in Finnconsult tender document, 16 April 1974, AMFA/12R/ML; invoice from Finnconsult to the MFA, undated, AMFA/12R/ML. [^]

- Henrik Westman, comment on Mtwara and Lindi projects, 14 March 1974, AMFA/12R/ML. My translation. [^]

- Martti Ahtisaari to MFA, 6 May 1974, AMFA/12R/ML. [^]

- OPM, ‘Guidelines on Technical Assistance for Increasing Planning and Control Capacity of Regions’, AMFA/12R/ML. [^]

- Henrik Westman, report on a field trip to Tanzania, 4 September 1974, AMFA/12R/ML. [^]

- OPM, ‘Guidelines on Technical Assistance for Increasing Planning and Control Capacity of Regions’, attached to a letter to the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland, 25 February 1974, AMFA/12R/ML. [^]

- OPM, ‘Guidelines on Technical Assistance for Increasing Planning and Control Capacity of Regions’, AMFA/12R/ML; ‘The Third Five-Year Development Plan 1975/76–1979/80’, 23 May 1974, AMFA/12R/ML. [^]

- Minutes of a meeting concerning agricultural planning in Mtwara, 23 September 1974, AMFA/12R/ML. [^]

- Henrik Westman, report on a field trip to Tanzania, 4 September 1974, AMFA/12R/ML. [^]

- For a problematization of the term ‘informal’ in this context, see, for example, Huchzermeyer 2014. [^]

- OPM to regional development directors, 23 May 1974, AMFA/12R/ML. [^]

- Minutes of a project survey meeting, 12 November 1974, AMFA/12R/ML. [^]

- Jaakko Salonen and Veikko Lappalainen’s travel itinerary for November and December 1974, undated, AMFA/12R/ML. My translation. [^]

- Lappalainen and Salonen to Finnplanco, 16 January 1975, AMFA/12R/ML. [^]

- Unto Korhonen and H. Eriksson, comment, undated, AMFA/12R/ML. [^]

- Project evaluation, 1982, AMFA/12R/AE. [^]

- Lizz Kleemeier, research report, 12 July 1982, AMFA/12R/AE. [^]

- Lizz Kleemeier, research report, 12 July 1982, AMFA/12R/AE. [^]

- Lizz Kleemeier, research report, 12 July 1982, AMFA/12R/AE. [^]

- Lizz Kleemeier, research report, 12 July 1982, AMFA/12R/AE. [^]

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Unpublished Sources

Mtwaran ja Lindin alueen kehittämissuunnitelma, 12R Tansania, AMFA/12R/ML, archives at the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

Aluesuunnitteluhankkeen evaluaatio, 12R Tansania, AMFA/12R/AE, archives at the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

Published Sources

Aggregate Architectural History Collaborative. 2022. Architecture in Development: Systems and the Emergence of the Global South. New York: Routledge.

Armstrong, A. 1987. Tanzania’s Expert-Led Planning: An Assessment. Public Administration and Development, 7(3): 261–271. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/pad.4230070303

Avermaete, T. 2010. Framing the Afropolis: Michel Ecochard and the African City for the Greatest Number. Oase: Journal for Architecture, 82: 77–89. https://www.oasejournal.nl/en/Issues/82/FramingTheAfropolis.

Beeckmans, L. 2018. The Architecture of Nation-Building in Africa as a Development Aid Project: Designing the Capital Cities of Kinshasa (Congo) and Dodoma (Tanzania) in the Post-Independence Years. Progress in Planning, 122: 1–28. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2017.02.001

Belshaw, DGR. 1982. An Evaluation of Foreign Planning Assistance to Tanzania’s Decentralized Regional Planning Programme, 1972–81. Applied Geography, 2(4): 291–302. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/0143-6228(82)90004-2

Berre, N. 2022. Karl Henrik Nøstvik: Remnants of Nordic Aid. In: Berre, N, Wenzel Geissler, P, and Lagae, J (eds.), African Modernism and Its Afterlives, 22–47. Bristol: Intellect. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv36xw79d.5

Berre, N, Wenzel Geissler, P, and Lagae, J (eds.). 2022. African Modernism and Its Afterlives. Bristol: Intellect. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv36xw79d

Bromley, R. 2023. Blending Globalism, Long-Term Futures, and Historical Sensitivities: The Audacity of Constantinos Doxiadis. Festival dell’architettura magazine, 61: 111–121.

Callaci, E. 2016. ‘Chief village in a nation of villages’: History, Race and Authority in Tanzania’s Dodoma Plan. Urban History, 43(1): 96–116. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926814000753

Chastain, AB, and Lorek, TW (eds.) 2020. Itineraries of Expertise: Science, Technology, and the Environment in Latin America’s Long Cold War. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvz939bd

Coulson, A. 1982. Tanzania: A Political Economy. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Dargent, E. 2014. Technocracy and Democracy in Latin America: The Experts Running Government. New York: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107446663

De Dominicis, F, and Tolic, I. 2022. Experts, Export, and the Entanglements of Global Planning. Planning Perspectives 37(5): 871–887. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2022.2116595

De Haan, A. 2009. How the Aid Industry Works: An Introduction to International Development. Sterling, VA: Kumarian Press.

De Raedt, K. 2014a. Shifting Conditions, Frameworks and Approaches: The Work of KPDV in Postcolonial Africa. ABE journal, 4(4). DOI: http://doi.org/10.4000/abe.3366

De Raedt, K. 2014b. Between ‘True Believers’ and Operational Experts: UNESCO Architects and School Building in Post-Colonial Africa. Journal of Architecture, 19(1): 19–42. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2014.881905

De Raedt, K. 2022. Transnational Exchanges in Postcolonial Zambia: School Buildings at the Intersection of Architectural, Political and Economic Globalization. In: Berre, N, Wenzel Geissler, P, and Lagae, J (eds.), African Modernism and Its Afterlives, 100–115. Bristol: Intellect. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv36xw79d.9

Doytchinov, G. 2012. Pragmatism, Not Ideology: Bulgarian Architectural Exports to the ‘Third World’. Journal of Architecture, 17(3): 453–473. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2012.692612

Ferguson, J. 1994. The Anti-Politics Machine: ‘Development,’ Depoliticization, and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Forss, K, Carlsen, J, Frøyland, E, Sitari, T, and Vilby, K. 1988. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Technical Assistance Personnel Financed by the Nordic Countries. N.p.: n.p.

Havnevik, KJ. 2000. The Institutional Context of Poverty Eradication in Rural Africa: Proceedings from a Seminar in Tribute to the 20th Anniversary of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

Herz, M, Schröder, I, Focketyn, H, and Jamrozik, J. 2015. African Modernism: Architecture of Independence. Zurich: Park Books.

Hodge, JM. 2007. Triumph of the Expert: Agrarian Doctrines of Development and the Legacies of British Colonialism. Athens: Ohio University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1j7x6pk

Huchzermeyer, M. 2014. Troubling Continuities: Use and Utility of the Term ‘Slum’. In: Parnell, S, and Oldfield, S (eds.), The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South, 86–88. Oxford, UK: Routledge.

Hydén, G. 1980. Beyond Ujamaa in Tanzania: Underdevelopment and an Uncaptured Peasantry. London: Heinemann. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1525/9780520312593

Jacob, W. 2018. Integrated Rural Development from a Historical and Global Perspective. Asian Education and Development Studies, 7(4): 438–452. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-02-2018-0022

Jennings, M. 2008. Surrogates of the State: NGOs, Development, and Ujamaa in Tanzania. Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press.

Kapur, D, Lewis, J, and Webb, R. 1997. The World Bank: Its First Half Century. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Keare, DH. 2001. Learning to Clap: Reflections on Top-Down versus Bottom-Up Development. Human Organization, 60(2): 159–165. DOI: http://doi.org/10.17730/humo.60.2.5yt2ya1297h7adjc

Kehitysyhteistyön vuosikertomus 1980. 1981. Helsinki: Ulkoasiainministeriö, Kehitysyhteistyöosasto.

Kilindo, AAL, and Mjema, GD (eds). 1995. Beyond Structural Adjustment Program in Tanzania: Successes, Failures, and New Perspectives. Dar es Salaam: Economic Research Bureau, University of Dar es Salaam.

Kiljunen, K. 1983. Finnish Aid in Progress: Premises and Practice of Official Development Assistance. Helsinki: Institute of Development Studies.

Kleemeier, L. 1988. Integrated Rural Development in Tanzania. Public Administration and Development, 8(1): 61–73. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/pad.4230080106

Koch, S. 2020. ‘The Local Consultant Will Not Be Credible’: How Epistemic Injustice Is Experienced and Practised in Development Aid. Social Epistemology 34(5): 478–489. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2020.1737749

Koch, S., and Weingart, P. 2016. The Delusion of Knowledge Transfer: The Impact of Foreign Aid Experts on Policy-Making in South Africa and Tanzania. Cape Town: African Minds. DOI: http://doi.org/10.47622/9781928331391

Koponen, J. 1998. Some Trends in Quantity and Quality of Finnish Aid, with Particular Reference to Tanzania and Nepal. Helsinki: Institute of Development Studies.

Laakso, M, and Tamminen, S. 2014. Rakentajat maailmalla: Vientirakentamisen vuosikymmenet. Helsinki: Suomen rakennusinsinöörien liitto.

Lal, P. 2015. African Socialism in Postcolonial Tanzania: Between the Village and the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316221679

Lamberg, E. 2021. Development Cooperation and National Planning: Analysing Finnish Complicity in Postcolonial Tanzania’s Decentralization Reform and Regional Development. Planning Perspectives, 36(4): 689–717. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2020.1851292

Lamberg, E. 2023. Yritystoimintaa, kehitysapua ja kylmän sodan diplomatiaa: Globaali arkkitehtuurivienti 1970-luvun Suomessa. In: Kummala, P (ed.), Murrosten vuosikymmen: Arki, aatteet ja arkkitehtuuri 1970-luvun Suomessa, 200–215. Helsinki: Arkkitehtuurimuseo.

Launonen, R, and Ojanperä, S. 1986. Integrated Rural Development: An Approach Paper. Helsinki: Institute of Development Studies.

Levin, A. 2022. Architecture and Development: Israeli Construction in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Settler Colonial Imagination, 1958–1973. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1215/9781478022503

Luanda, NN. 1998. Donors and Poverty in Lindi and Mtwara Regions. Helsinki: Institute of Development Studies.

Mack, J. 2019. An Awkward Technocracy. American Ethnologist, 46(1): 89–104. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12736

Mehos, DC, and Moon, SM. 2011. The Uses of Portability: Circulating Experts in the Technopolitics of Cold War and Decolonization. In: Hecht, G (ed.), Entangled Geographies: Empire and Technopolitics in the Global Cold War, 43–74. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/8357.003.0004

Mesaki, S, and Mwankusye, J. 1998. The Saga of the Lindi-Kibiti Road: Political Ramifications. In: Koda, B, and Seppälä, P (eds.), The Making of a Periphery: Economic Development and Cultural Encounters in Southern Tanzania, 75–117. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

Mitchell, T. 2002. Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-Politics, Modernity. Berkeley: University of California Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1525/9780520928251

Nnkya, TJ. 2008. Why Planning Does Not Work: Land Use Planning and Residents’ Rights in Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: Mkuki Na Nyota.

Nyerere, JK. 1968. Ujamaa: Essays on Socialism. Dar es Salaam: Oxford University Press.

Okoko, KAO. 1987. Socialism and Self-Reliance in Tanzania. London: KPI.

Payer, C. 1983. Tanzania and the World Bank. Third World Quarterly 5(4): 791–813. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/01436598308419732

Phokaides, P. 2018. Rural Networks and Planned Communities: Doxiadis Associates’ Plans for Rural Settlements in Post-Independence Zambia. Journal of Architecture 23(3): 471–497. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2018.1458044

Porvali, H. 1995. Evaluation of the Development Cooperation Between the United Republic of Tanzania and Finland. Helsinki: Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Department for International Development Cooperation.

Prakash, V, Casciato, M, and Coslett, DE. 2022. Rethinking Global Modernism: Architectural Historiography and the Postcolonial. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781003120209

Putri, PW. 2020. Insurgent Planner: Transgressing the Technocratic State of Postcolonial Jakarta. Urban Studies, 57(9): 1845–1865. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019853499

Rweyemamu, JF. 1969. International Trade and the Developing Countries. Journal of Modern African Studies 7(2): 203–219. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X00018280

Rweyemamu, JF. 1971. The Causes of Poverty in the Periphery. Journal of Modern African Studies 9(3): 453–455. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X00025192

Rweyemamu, JF. 1972. Towards Socialist Planning. Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Publishing House.

Rweyemamu, JF. 1973. Underdevelopment and Industrialization in Tanzania: A Study of Perverse Capitalist Industrial Development. Nairobi: Oxford University Press.

Schneider, L. 2004. Freedom and Unfreedom in Rural Development: Julius Nyerere, Ujamaa Vijijini, and Villagization. Canadian Journal of African Studies, 38(2): 344–392. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.2004.10751289

Schneider, L. 2007. High on Modernity? Explaining the Failings of Tanzanian Villagisation. African Studies, 66(1): 9–38. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/00020180701275931

Scott, JC. 1998. Seeing like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sedighi, M. 2018. Megastructure Reloaded: A New Technocratic Approach to Housing Development in Ekbatan, Tehran. ARENA Journal of Architectural Research, 3(1): 1–23. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/ajar.56

Siitonen, L. 2005. Aid and Identity Policy: Small Donors and Aid Regime Norms. Turku: Turun yliopisto.

Silva, CN (ed.). 2020. Routledge Handbook of Urban Planning in Africa. London: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781351271844

Stanek, Ł. 2020. Architecture in Global Socialism: Eastern Europe, West Africa, and the Middle East in the Cold War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9780691194554

Stanek, L. 2012. Miastoprojekt Goes Abroad: The Transfer of Architectural Labour from Socialist Poland to Iraq (1958–1989). Journal of Architecture, 17(3): 361–386. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2012.692603

Tanzanian Government. 1975a. Lindi Region: Integrated Development Plan for 1975/76–1979/80. Helsinki: Finnplanco.

Tanzanian Government. 1975b. Mtwara Regional Integrated Development Plan, 1975–1980. Helsinki: Finnconsult.

Tolić, I. 2022. News from the Modern Front: Constantinos A. Doxiadis’s Ekistics, the United Nations, and the Post-War Discourse on Housing, Building and Planning. Planning Perspectives 37(5): 973–999. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2022.2110930

Ulkoasiainhallintokomitean 1974:n mietintö. 1975. Helsinki: Valtioneuvosto.

Unger, CR. 2019. International Organizations and Rural Development: The FAO Perspective. International History Review 41(2): 451–458. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2018.1460387

Vais, D. 2012. Exporting Hard Modernity: Construction Projects from Ceaușescu’s Romania in the ‘Third World’. Journal of Architecture, 17(3): 433–451. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2012.692611

Voipio, T. 1998. Poverty reduction in Mtwara-Lindi 1972–1995. A history of paradigm shifts. In: Koda, B, and Seppälä, P (eds.), The Making of a Periphery: Economic Development and Cultural Encounters in Southern Tanzania, 75–117. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

von Freyhold, M. 1979. Ujamaa Villages in Tanzania: Analysis of a Social Experiment. London: Heinemann.

White, P. 2020. Bastard Children: Unacknowledged Consulting Companies in Development Cooperation. International Development Planning Review, 42(2): 219–240. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2019.36