Introduction

In 1959, after a short visit to Guinea-Bissau, at that time still called Portuguese Guinea, the Italian journalist Emile Marini wrote,

I left Guinea with a feeling of having abandoned one of those places that become dear to us … from where one brings memories of peace, beauty and calm, with a sense of profound admiration for the European Portuguese of which, down there, we can really say that they share their lives, with love and competence, with the natives.1

For Marini, Portuguese colonialism was not racist; on the contrary, he believed Portugal’s behaviour in its colonies put that of other imperialist countries to shame. Sixty years later, the discussion persists. In June 2020, a primetime televised debate asked, ‘Portugal, a racist country or not?’ Some of the commentators diagnosed several racist practices in contemporary Portugal, while others claimed that not only is Portugal not racist today but it never was, when historically compared with other European imperial powers, thus agreeing with Marini. This ongoing discussion can be best summarized by the words of activist Vanusa Coxi: ‘Portugal itself is not a racist country, but there is racism in Portugal’ (Carlos 2020). The problem, in part, is the question, Is Portugal racist? Whether a country is racist or not is less important than first simply acknowledging that racism is present and then proceeding to understand how that fact is affected by certain historical experiences. For Portugal, this involves facing up to luso-tropicalism and the ramifications of its concrete effects.

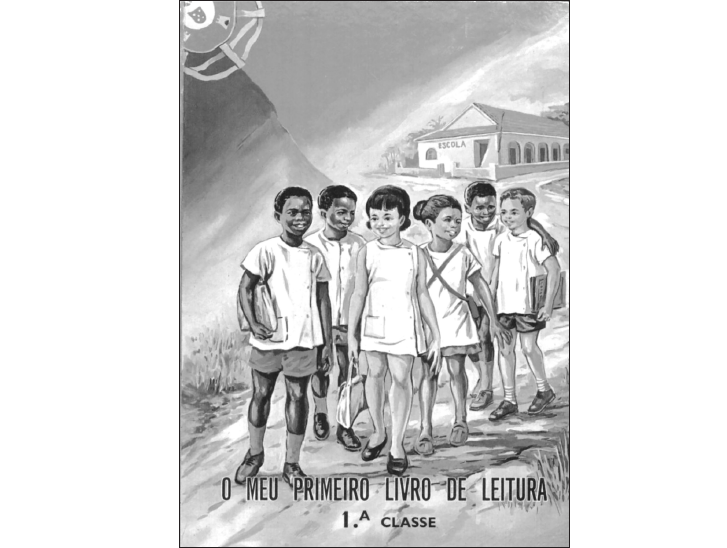

Luso-tropicalism posits that Portugal created peaceful multi-racial colonial situations in the Global South. By Marini’s time, many believed — and many still do — that a benevolent form of colonialism was exclusive to the Portuguese, distinguishing itself from the supposedly more destructive and extractive colonial endeavours of other European colonizers. This thesis entered scientific discourse with the work of Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre (1933). By the 1960s, it became a governing discourse buttressing Portuguese colonialism, harnessed by the dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar and Marcello Caetano, lasting from 1933 to 1974. The luso-tropical narrative is an intellectual tradition about the country’s long history with Africa, Europe’s ‘dark continent’ (Mbembe 2001: 2), initiated during the nation-building 19th century and all its anxieties about race and culture. This intellectual tradition contained a national utopia, combining older Christian evangelization with the colonial mission civilisatrice, the civilising mission of colonialism: a trans-continental Portuguese culture created by miscigenação, or the mixing of races over time, and Christian values (Figure 1).

Educating the luso-tropical empire. Cover of a colonial primary school manual for Guinea-Bissau from 1972, O meu primeiro livro de leitura [My first reading book] (published in Portugal for the Government of the Province of Guinea). Online at Memoria de Africa, Univesidade de Aveiro, memoria-de-africa.ua.pt, http://memoria-africa.ua.pt/Library/ShowImage.aspx?q=/geral/L-00000012&p=1.

This paper examines how this utopia was articulated in the concrete production of urban colonial Guinea-Bissau through planning practices, housing schemes and lived experience. However, little is known of Guinea-Bissau’s urban and architectural history because of its peripheral status in Portuguese colonial history and the latter’s peripheral status in the history of European colonial architecture. When Guinea-Bissau is the focus of architectural academic attention, it is for its colonial achievements, to the detriment of all other topics.2 For the purposes of advancing the luso-tropical utopia, as this paper will show, Guinea-Bissau constituted a laboratory for Portuguese colonial practices until 1974, particularly with housing programs. Furthermore, Guinea-Bissau’s history as a colony of Portugal is enlightening for the ways it reveals the shocks and tensions of imperial modernity and extractive colonialism, especially given its late and precarious dominion by Portugal. The military campaign for the occupation of Guinea-Bissau began in the 1840s, earlier than in Angola and Mozambique (where it began in the 1890s), and lasted until the 1930s. During this period, and even after, the Portuguese were present only in a few coastal towns, legacies of the trans-Atlantic trade in enslaved people, such as Cacheu, Bissau and Bolama. Unlike Angola, which was a settler colony fed by its rich hinterland economy and thus had settlers spread throughout, settlers in Guinea-Bissau lived in those few strongholds and were not very engaged in the exploration of the hinterland, nor even particularly in contact with it. Well into the late 1960s, most people living in Guinea-Bissau were either completely disengaged from or in tense relationships with colonial urbanization and the capitalist circuits dominated by Europe. Particularly challenging for imperial dreams of development were the geography and ecology of the small land mass, criss-crossed by rivers and alluvial plains dramatically affected by the harsh rhythm of monsoon and dry seasons. The thirty years of colonial ‘peace’, from the 1930s to 1963, when the war for liberation began, thus constitute a particularly condensed episode of the ambitions, tensions and failings of colonial modernization.

Using original archival research in military archives, until recently neglected by architecture historiography, and long-term field work in Guinea-Bissau, the paper aims to show how architecture and planning practices enabled the luso-tropical horizon as a form of government, giving shape to a contradictory set of experiences.3 To accomplish this, it addresses three moments in colonial spatial production, discussing how particular urban plans and housing schemes articulated ‘Indigenous Law’, scientific colonialism and strategies to hold power: 1) the immediate post-WWII period, when the neighborhood of Santa Luzia was developed; 2) the period from the 1950s to the 1960s, in which Portuguese architects focused on ‘indigenous’ dwelling cultures; and 3) the period from the 1968 to 1974 (the year of liberation), in which the Portuguese military enforced a villagization program. First, however, we must start by justifying luso-tropicalism as a spatial argument.

Bissau 1940s to 1950s: Crafting an Ideal Portuguese Africa

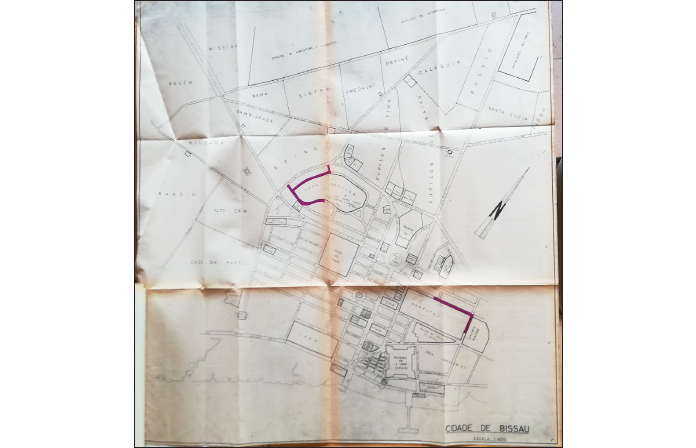

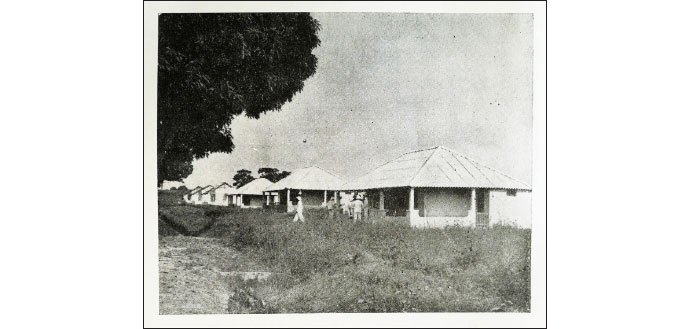

If you ask any taxi driver in Bissau to take you to the city centre, you will get the question: ‘Praça?’ You might think the driver is asking if you mean the city’s central square (‘praça’ means central square), but no, the question is asking if you mean the urban perimeter of Bissau’s first colonial urban plan. Known as the ‘New Bissau’ of 1919, it was conceived by the engineer José Guedes Quinhones and was mostly realized by the Portuguese dictatorship after Bissau became the colony’s capital in 1941 (Milheiro 2012a). The moment the taxi arrives at the urban perimeter of this area, emerging from busy avenues into calm, low-density streets, the question becomes, ‘So where in Praça?’ For ‘Praça’ refers to the whole former colonial city where the Portuguese settlers lived and from where the colonial administration ruled the country. Beyond this perimeter lay what Quinhones called the ‘suburbs’, where most Guineans lived during the colonial period (Figures 2, 3). This city beyond the perimeter was, and still is, a totally different kind of city than you might expect. Not only is it riddled with irregular streets and alleys, but its architectures are of transient materials that rarely belong to the architectural historian’s lexicon (Figure 4). Beyond the old colonial city’s perimeter, irregular streets grow out of two avenues connecting the city to an old Portuguese military garrison and the airport, the neighborhoods in-between are assemblages of single-storey houses, mostly mud brick with zinc panels for roofs.4

Map of Bissau’s road works for 1971 (based on Figure 2). Redrawn for clarity by Rui Aristides Lebre.

This tale of two cities repeats a larger international pattern of exclusion and asymmetrical urbanization whose roots are in modern colonialism (Holston 2008), particularly evident in former Portuguese colonies, although not exclusive to those in Africa (Myers 2011). It is a concrete reminder that luso-tropicalism and its supposed multicultural modernity was a mirage. The idea of luso-tropicalism itself was not Portuguese but Brazilian and served Brazil’s state building project in the early 20th century. Gilberto Freyre developed a historical reading of Portugal’s ‘beneficial’ colonialism in his famous book Masters and Slaves (1946 [1933]) as a way to argue that Brazil was essentially a multi-racial society. It was picked up by the Portuguese dictatorship in the 1950s, in the midst of a growing need to defend the empire leading up to the Bandung Conference of 1955, when leaders from countries in Asia and Africa met to discuss security and economics in the context of the Cold War. Freyre’s work, however, had already been read by Portuguese elites well before 1955 (Almeida 2004; Anderson et al. 2019). When the dictatorship’s propaganda apparatus picked up on the idea, involving a degree of mistranslation (Macagno 2018) and ‘U-turns’, the dictator Salazar was initially against Freyre’s historical reading because of his aversion to the idea of miscegenation. At its inception, the Portuguese dictatorship promoted a ‘blood and soil’ cultural policy emphasizing racial purity, like all other European fascisms. Thus, Freyre’s luso-tropicalism thesis was understood as contradicting the ‘racial purity’ that originally clad the dictatorship’s ideological platform. This changed after the Second World War. With the growing movements for decolonization, Freyre’s luso-tropicalism went from marginal intellectual discourse to official state speech, as it helped the dictatorship argue that its colonies were in fact ‘regions’ of one same country and culture. By the 1960s, the thesis of luso-tropicalism was officially part of the curricula of schools that taught colonial administration and social and political science, soon becoming a popular myth about Portuguese lineage from humanist seafarers. While for some, luso-tropicalism was a blatant lie, possibly for most and certainly for the regime it was a political destiny: colonialism was argued to be a humanitarian endeavour and a civilisational right (Castelo and Alves 2019; Fykes 2009; Anderson et al. 2019). More than an ideology, it became a ‘space-time horizon’ desired by both Portuguese and Africans (Castela 2018) as it gained the concreteness of its desire through the production of actual bodies in colonial space. In 1947, the ambitious colonial administrator Sarmento Rodrigues, one of the dictatorship’s reformers and governor of Guinea-Bissau from 1945 to 1949, then minister of the colonies in Lisbon, and from 1961 to 1964 governor of Mozambique (Silva 2008), addressed Portuguese colonial administrators gathered in Bissau a month before the city was to host the second Conférence internationale des Africanistes Occidentaux (CIAO). He had this to say about the forthcoming event and the significance attached to its location in this dual city of Bissau:

This event constitutes yet another proof, one of the most expressive at that, not only of the preponderant situation of our country, but particularly of the attention Guinea deserves among the most illustrious international scientific fields. Who could say to those troubled settlers earlier in this century that that Bissau surrounded by palisades would, in so little time, be the welcoming city of today? That the so disquieted Guinea would become this appeasing garden, where one lives peacefully in the fraternity of work and mutual respect?5

The biannual CIAO conference that Bissau was soon to host came under the initiative of France’s Institute français d’ Afrique noir (IFAN), whose purpose was to share knowledge and coordinate development across various African colonies Founded in January 1945, the CIAO was a response by European colonizers to pressure from the United Nations to grant their colonies independence. The first conference of West Africanists was hosted in Dakar and gathered ethnologists, botanists, geographers, physicians, and other experts from Spain, Portugal, France, and England.6 These conferences fostered networks of knowledge that served the practical arts of governing colonial fields and bodies (Ágoas and Castelo 2019) and were essential for the creation of international apparatuses coordinating rule and development across several former African colonies, such as the Commission for Technical Cooperation in Africa South of the Sahara (CCTA), founded in 1950 by CIAO’s founding members.

Bissau in 1947 was, thus, the centre of this defensive modernization. Rodrigues was celebrating not only the accomplishment of Quinhones’ Praça and the promise of Bissau’s luso-tropical future but also the city’s leading role in this international setting — and, of course, his success as a colonial manager. He had reason to do so. During his time as governor, he promoted several public works, disease control campaigns and topographical and agricultural surveys and founded the Centro de Estudos da Guiné Portuguesa (Center of Studies of Portuguese Guinea), whose Boletim Cultural da Guiné Portuguesa (Cultural Bulletin of Portuguese Guinea) became a leading scientific publication in the Portuguese colonies (António 2008).

Indeed, post-war colonial modernization mobilized new scientific apparatuses. There was a renewed concern with ethnography, censuses, and a general attention to African ways of life, of respecting the ‘indigenous’ as a form of rule. As was common in modern European colonialism in Africa, respecting ‘indigenous culture’ meant seeing and placing Africans as a separate entity, socially, legally, and politically. Portugal’s ‘Indigenous Law’ of 1928–33 officially excluded Africans from claiming basic citizen rights, while containing the notion of a civilizational progression open to Africans who might want to join the ‘fraternity of work and mutual respect’ (Ferreira and Veiga 1957). First formulated with the colonial labor law of 1928, which forced African populations to do yearly mandatory work, the Indigenous Law effectively assured Portugal’s access to slavery in the 20th century. The Colonial Act of 1930, promulgated by the dictatorship, reinforced this situation; it was abolished in 1961, when the liberation wars began in Angola. This late abolishment of forced labor was both a real change and a clever political maneuver by the dictatorship to rally African populations to the colonial cause while maintaining the structural asymmetries of labor relations (Meneses 2010). The dual city of Bissau was thus not understood as the result of a strict racial separation but as the mark of this ‘cultural respect’ (Castela 2010: 81).

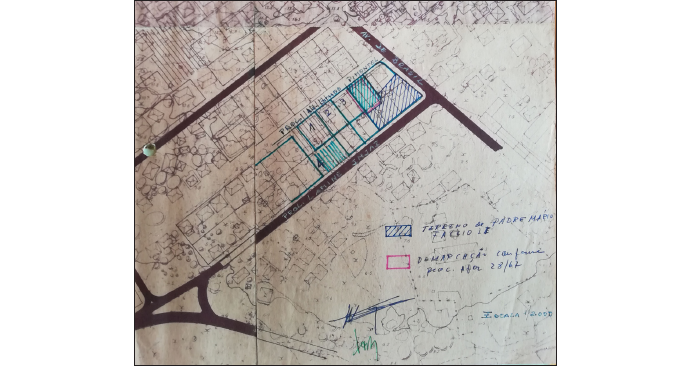

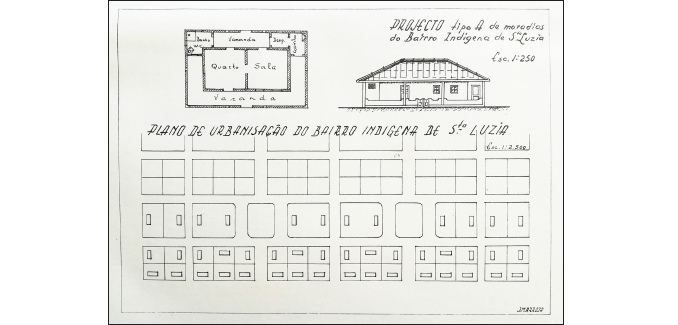

If Praça was the Portuguese city and the suburbs the ‘indigenous’ one, in 1946 Rodrigues attempted a ‘third’ city by proposing the first ‘Indigenous Urbanization Plan’ that resulted in the Santa Luzia housing scheme, located along the avenue connecting the city centrer to the military garrison towards the northeast. Santa Luzia was intended to be the shining example of the colonial ladder at work and the first of its kind in the Portuguese colonies (Figure 5). Although scarce, housing programs would hence become a central mechanism for the creation of African subjectivities along the lines of a desired luso-tropical nation. The scheme was intended for ‘assimilated’ Guineans — those who worked under the colonial administration and were willing to behave, if only superficially, like Christian Portuguese, adopting monogamy, becoming fluent in the Portuguese language, and using modern cutlery and furniture, among other social rites and symbols of the colonizer. The scheme’s financial structure was as important as its enforced social protocols, enabling the creation of landowners through the payment of small instalments to the colonial administration. This represented a radical break with existing land ownership structures in Guinea-Bissau, which were often non-monetized social exchanges under the purview of local ‘big men’.7

The first row of houses in the Santa Luzia neighborhood (Mota and Neves 1948: 11).

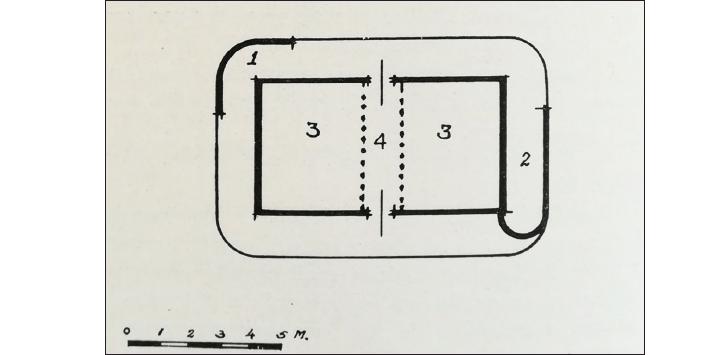

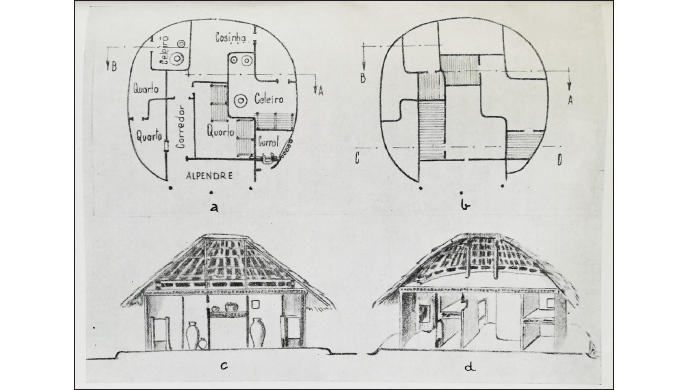

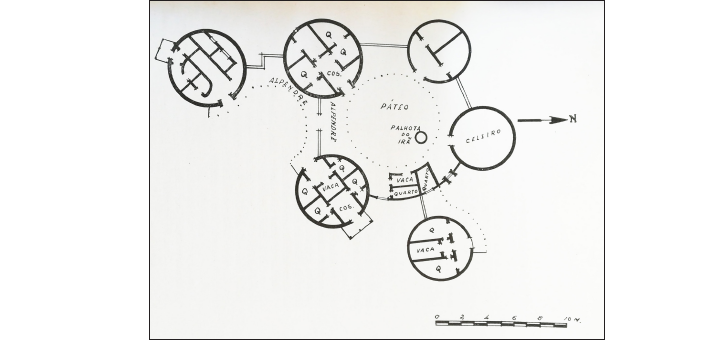

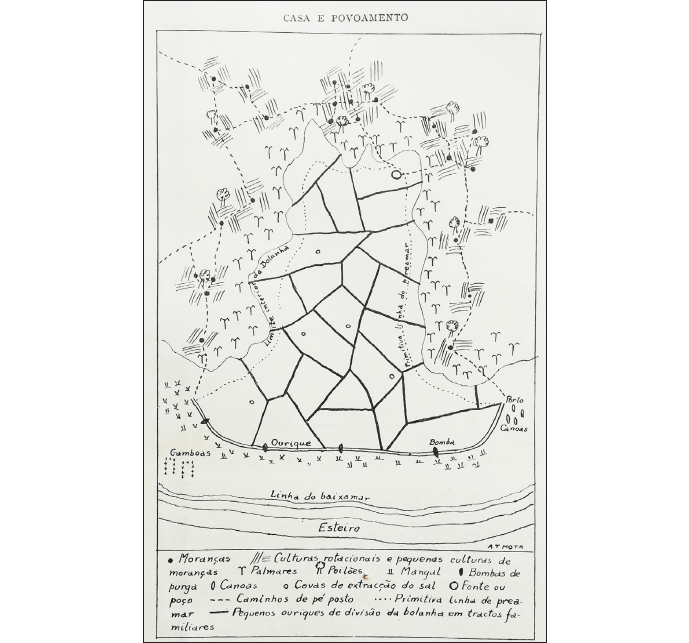

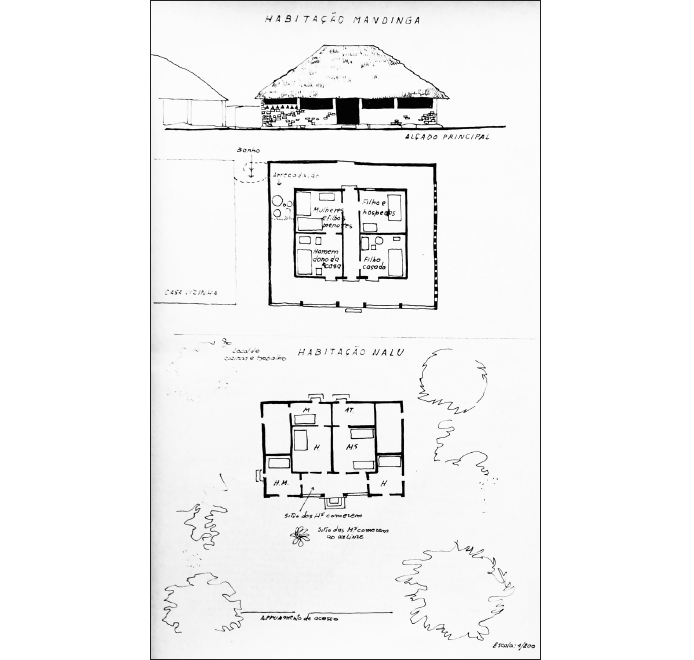

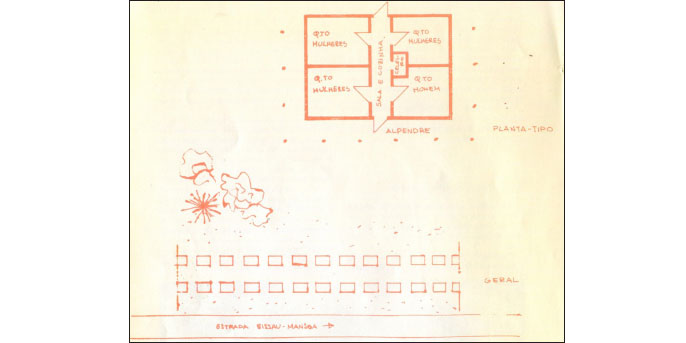

The model house of the Santa Luzia scheme had a rectangular core with two rooms, framed by a perimetral veranda, at the corners of which were placed the bathroom and kitchen. The house was an isolated object, similar to a modern suburban house, with front and back gardens (Figure 6). The design appears to be a functional adaptation of Guinean dwelling architectures, particularly inspired by architecture from the Manjaco and Balanta societies. The Center of Studies of Portuguese Guinea had just conveniently finished a survey of Guinean dwelling practices (Mota and Neves 1948). It identified Manjaco houses as often square and built with simple lines, mostly bereft of ornament (Figure 7), while Balanta houses, usually part of a compound, were often identified as round, sometimes presenting elaborate decorations in communal areas (Figure 8). The Manjaco house appears to have inspired Santa Luzia’s simple rectangular layout, while the Balanta its decorated verandas. This represented a simplification, reducing dwelling to abstract shapes far removed from their elaborate social, aesthetic, and ecological structures. As the survey of 1948 implies, by then most dwellings in Guinea-Bissau constituted ‘introverted’ compounds, organized by complex functional and social dynamics, often with curved and round designs, more effective for cob and rammed-earth construction techniques (Figure 9).8 In fact, the survey showcases considerable variety in the architecture of Guinea-Bissau, not just in terms of architecture but also in the layout of towns, villages, and neighborhoods. For instance, the Beafada people usually built along main thoroughfares in a grid; Fulas, of the Fulani community, built in concentrated groups of compounds; and the Balanta people in scattered compounds (Figure 10).

Plan, elevation, and layout of Santa Luzia neighborhood. From Mota and Neves (1948).

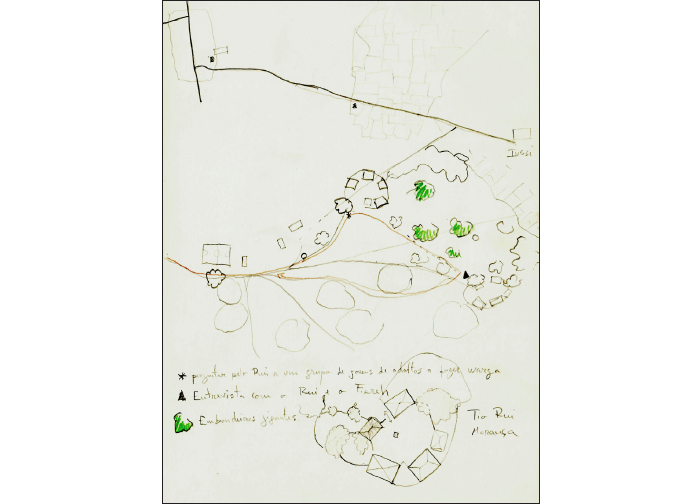

Sketch of the layout of a housing unit in the Manjaco de Caió area. From Mota and Neves (1948).

Plan and section of a Balanta house. From Mota and Neves (1948).

Plan of a compound in Biombo. From Mota and Neves (1948).

Why draw inspiration from Manjaco layouts and Balanta ornament? One possible reason is that Manjaco and Mandinga Guineans were historically closest to the Portuguese, having established fruitful commercial relationships since the 19th century, while the Balanta constituted one of the largest ethnic groups (30% of Guinea-Bissau’s total population in the 1950s). Balanta communities, however, where mostly concentrated in the southern regions of Quínara and Tombali, and given their resistance to hierarchical power structures, usually lived in scattered villages along rice paddies and were hostile to Portuguese colonial efforts (Figure 11). Santa Luzia therefore spoke an architectural language that was both comforting to the colonizer and cogent with the fact it was intended for those Guineans working for the colonial administration who were supposed to signify the middle way between ‘indigenous’ and ‘civilized’. One of Santa Luzia’s first dwellers was a chauffeur for the colonial government’s mission to eradicate mosquitos in the 1940s, and his son ‘Alberto’ lives there still.9 Being Manjaco, Mandinga, or Balanta had little to do with getting a place there. Santa Luzia’s plan and house design was above all a testing ground for colonial ‘assimilation’, for which ‘cultural respect’ was a device by which the ‘assimilated’ were established as distinct social subjects within the city. The functionalist interpretation of dwelling traditions implied a somewhat arbitrary colonial respect that did not allow its dwellers many liberties.

Sketch of a Balanta village landscape. From Mota and Neves (1948: 97).

As soon as people moved in, they began to alter their houses (Varanda 1968: 32), adding a new room here and there, enlarging its layout, at times creating a compound, as we can witness today (Figure 12). The original grid that placed houses in an ‘extraverted’ relationship with the street was soon lost to a construction of intimacy. The front and back gardens of the original modern suburban layout were soon both occupied by new buildings and fittings. In fact, away from the main street, the 1946 plan is nowhere to be found. Alberto’s father’s house, for instance, is an intense and ongoing living construction site, expanding and contracting as family and funds allow — Alberto’s heritage inscribed in the building itself.

By 1968, the Santa Luzia urbanization plan was still only partially built, and it never would be fully realized. While the house model, inspired by an idea of luso-tropical ‘respect’, was soon subverted by its actual use, the Santa Luzia neighborhood that was accomplished did promote a Guinean urban elite that by small instalments became proprietors of Rodrigues’ vision of Bissau. The change in status of some did not stop people like Alberto’s father from joining the independence movement in the 1960s and choosing a free Guinea-Bissau over a luso-tropical one. Nevertheless, Santa Luzia was a key experiment in colonial housing practices that joined urban modernization with the creation of an ‘assimilated’ African citizenship. For this purpose, the Santa Luzia house deployed a dialogue between the ethnographic survey, such as the above-mentioned survey of 1948, and an architectural invention that was slowly maturing. Henceforth, the luso-tropical utopia would tie anthropology to architecture in a close, albeit difficult, intimacy.

Architectural Discourses on Luso-Tropicalism, 1950s to 1960s

International pressure and the growing organization of African liberation movements made the 1950s and 1960s a period of intense colonial modernization through ‘development’ (Ferguson 2006; Hodge, Hödl and Kopf 2014). The directive to ‘develop’ also resulted from a European reorganization of economic interests in Africa within the emerging framework of the European Economic Community (Hansen and Jonsson 2014). During this period, white settler communities increased exponentially in Angola and Mozambique, where economic growth, fueled by the European pursuit of raw materials, sparked, for instance, the post-war coffee boom in Angola. Urban studies and plans were commissioned and new development organizations created, such as the Provincial Institutes of Settlement in Angola and Mozambique, to promote rural modernization through the creation of white settler communities. However, little was accomplished in the way of housing black African populations. Such was the case in Guinea-Bissau, where the lack of a profitable hinterland made rural modernization even less desirable. The climax of this illusory progressiveness was the appointment of Adriano Moreira as the new overseas minister in 1961; during his short two-year tenure, he framed Portuguese colonialism as a pluri-racial modernizing endeavor in the wake of Freyre’s national fame. Moreira’s supposedly progressive colonial agenda was in fact a palliative for a period of violence that had just begun, with the massacres in the cotton regions of Angola that would turn into the start of the liberation wars in 1961, 1963 in Guinea-Bissau and 1964 in Mozambique. So, while the 1960s was a period of intense luso-tropical propaganda, colonial cities were in fact ‘whitening’, and the gap between black Africans and Portuguese was increasing.

Propelled by colonial ‘development’, Portuguese scholars of anthropology and architects were experimenting with new references and problems. In anthropology, the social darwinism of the 1940s (Almeida 2008) gave way to Boas-inspired anthropologists under the influence of Jorge Dias, concerned less with tying ‘cultures’ to rungs in the civilizational ladder and more with perceiving language, ritual, and shape as independent phenomena yet connected (Viegas and Pina-Cabral 2014).10 A new generation of architects was also developing a spatial anthropology of Portuguese dwelling and reinventing a need to connect space to ‘Land and People’ (Lebre 2017), its key turning point being a survey of Portuguese vernacular architecture titled Arquitectura Popular em Portugal (SNA 1962). For modern architecture to be truly modern, according to this generation, it had to start from culture.

Various architects working in the colonies picked up on the idea of architecture’s cultural dimension to address the colonial problem of the immense gap between white Portuguese settler spatialities and those of black Africans, i.e., the failure of luso-tropical development. Confronting this, the new generation of architects understood the luso-tropical utopia as a standpoint from which to build the colonial ‘Land and People’. The architect Mário Gonçalves de Oliveira is an illustrative example. In 1946 he started a long career in the Colonial Planning Office of the Overseas Ministry that ended with this office’s extinction in the Carnation Revolution of 1974 (Milheiro 2012b; Diniz 2013). Guinea-Bissau drew his attention, and he surveyed Guinean dwelling practices as pristine representations of ‘indigenous culture’, much as Mota and Neves (1948) had a decade before. With this amateur ethnographic attention, shared by other architects, such as Fernando Schiappa de Campos, his colleague in the Colonial Planning Office, luso-tropicalism was projected into urban form.

In 1961, Oliveira drew an urban plan for low-income housing in Bissau which showcases this approach. In it, the main concern for Portuguese architects working in the colonies, he argued, should be to create ‘urban structures of conviviality and integration’. This meant being able to design urban forms and neighborhood units for the ‘beneficial policy of conviviality and development of pluri-racial communities, by us long practiced’ (Oliveira 1962: 10). This formulation literally mirrored the argument of pluri-racial modernization promulgated by Moreira, who was a close friend (Diniz 2013). For Oliveira, this challenge was compounded by the ‘primitive state of development’ of Guineans, as well as by the primitive state of many Portuguese. Upon observing how ‘Europeans’ dwelled in Santa Luzia, he identified the need for ‘more evolved’ Europeans, with a ‘more valid culture’ capable of ‘civilizing … natives and non-natives’ (Oliveira 1962: 16, 27). In fact, the ‘lack of culture’ of Portuguese settlers’ was a recurring problem for colonial authorities throughout this period. Oliveira’s solution, particularly for a ‘well organized distribution of the house’, was based on realizing that ‘the congenial modification of the psychobiological personality of the less evolved natives could be taken to effect … by the organization of well elaborated units of conviviality’ (1962: 12).

To attain the luso-tropical horizon, urban planning and house design were supposed to transform the colonial city into a sort of disciplining apparatus organized in structures of influence. Oliveira’s plan for Bissau divided social groups into different neighborhood units whose ‘organic’, vernacular-inspired design would convey ‘cultural respect’ and thus help educate about it. The plan was never built, however. In fact, during the 1950s and especially in the 1960s, the colonial administration engaged in little urban construction. The exception was the Ajuda neighborhood, proposed in 1965 as response to a fire in Bissau’s ‘indigenous suburbs’. Although informed by the luso-tropical approach of Oliveira and others, the house model in this neighborhood departed very little from the original Santa Luzia house model: a square plan with three rooms, surrounded by a veranda, located in the middle of the plot in an ‘extraverted’ relationship with the urban setting. This was not a simple reproduction of the Santa Luzia model, as the house plan exhibits certain functional changes, however, the scheme deployed a similar approach of vernacular inspiration but broke the dwelling into separate and abstract building blocks that could be used at will. This destructive abstraction was further combined with an infatuation with square house plans from the ‘more evolved’ Guineans, such as Mandinga people’s urban houses in Bissau, that figure prominently, for instance, in a 1968 urban survey of Bissau (Figure 13).

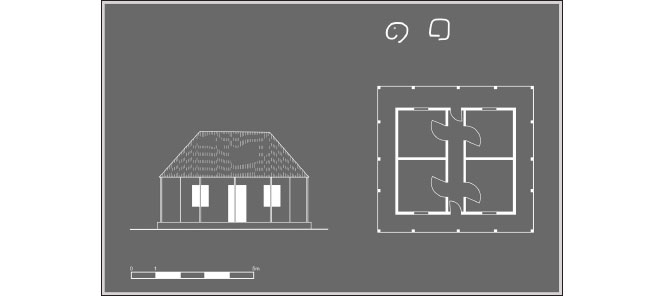

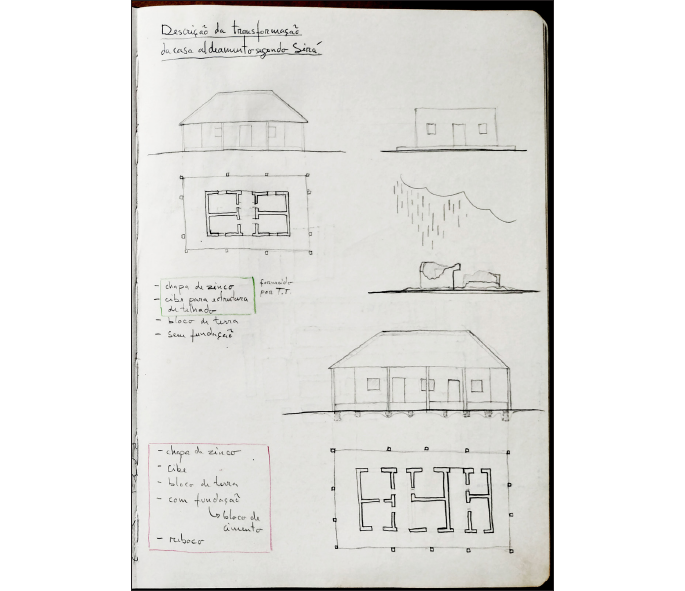

The fact was that a modern architecture for ‘pluri-racial communities’ mostly remained on the drawing board, and thus the luso-tropical horizon assumed the form of critique. Fernando Varanda, an architect of the new generation, presented a clear illustration of this in his review of colonial housing policy from 1945 onwards (1968) — mainly addressing the Santa Luzia and Ajuda schemes. He claimed that these ‘raise serious doubts about their effective working and reply to the needs of the involved population’ (Varanda 1968: 36–38). Both models were, in his words, of ‘rule and square’, meaning abstract and delocalized (Figure 14). In both, the veranda was more of a problem than a solution because it disregarded the ‘life system of community tradition left to blacks in Guinea’ (1968: 38). He also criticized its construction methods and materials, particularly the replacement of local clay, dirt, wood, and straw construction with concrete and cement block structures with roofs clad in zinc, all materials supplied by the colonial market and directly tied to the Portuguese dictatorship’s industrial oligarchs. According to Varanda this break with local construction methods and materials was a blind rejection of a working environmental model. Finally, Varanda was perhaps the only architect of his generation to openly recognize that Islamic communities, which constituted the great majority of Guinea-Bissau’s population, as they do today, were excluded from design thought (1968: 39).

Drawn reproduction of a study of a common house design in Bissau, demonstrating the rigidity of the ‘rule and square’. From Varanda (1968: 30)

Like Oliveira, Varanda proposed a new house model. It worked with family aggregates, based upon the idea of the morança, or family compound. Houses, he suggested, should be co-built by Guineans, with clay walls, wood, and straw, as found in common Guinean houses. The shape of the house directly resulted from a reinterpretation of vernacular forms and solutions, such as the use of few and small windows and small verandas, among other surveyed elements. Varanda’s housing scheme was also never built, although its design approach reappears in postcolonial Guinea-Bissau (Meuser and Dalbai 2021).

For both Oliveira and Varanda, ethnographic attention to design traditions played an important role in bringing about ‘development’ through ‘colonial respect’. Such development provided a new creative path for a new generation of Portuguese architects invested in bringing about a luso-tropical modernity. In fact, these paper architectures — for most were unbuilt — perpetuated both the aura of possibility for the luso-tropical horizon as well as the potential shape and idealized urban life it might take. However, and as Varanda shows, this horizon became, at best, a propositive critique of the colonial present, never strong enough to face the performative role of luso-tropicalism in colonial extraction and its asymmetrical production of development. War was the result.

‘Socio-economic Maneuvers’ or Forced Villagization in Guinea-Bissau, 1968–74

The main reason very few housing schemes were promoted in Guinea-Bissau from the late 1950s onward was the onset of the liberation wars, in 1961 in Angola, 1963 in Guinea-Bissau, and 1964 in Mozambique. While deeming civilian housing and planning programs from colonial administrations as second in priority to military operations, the Portuguese armed forces brought about the largest housing experiment ever conducted by the Portuguese state. Its villagization program was a ‘hearts and minds’ military strategy that involved forcibly resettling African peasants in controlled camps, separating populations from their liberation movements while attempting to rally these to the colonial cause through some measure of development. First begun in 1961 in Angola as an emergency response to returning refugees, the villagization program was implemented in the mid-1960s in Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau, eventually resettling up to two million people in the three countries (Bender 1978; CECA 2006).11 In Guinea-Bissau, the Portuguese military referred to it as ‘socio-economic manoeuvres’,12 part of António de Spínola’s spin on the Portuguese war strategy after 1968.13 Spínola, a cavalry general educated in Germany, was close to Salazar and one of the dictatorship’s ‘strong men’ who, when assigned to Guinea-Bissau in 1968, already had an accomplished military record in Angola. Forced villagization, with its resettlement of African population and supposed development measures, was key, he claimed, to bringing about ‘the civilizational and multiracial attributes of our blissful nation’ (Barbosa 2007: 394). The luso-tropical utopia had re-emerged with a military purpose.

By the late 1960s, forced resettlement, as part of Spínola’s war plan, became the backbone of the Portuguese war strategy. It applied the lessons from other North Atlantic states, such as the British forced resettlement plan of Kikuyu (1954) in Kenya and the ‘new village’ scheme (1950–52) in Malaysia, and the French ‘centres de regroupement’ in Algeria (1954–62) (Nyce 1973; Henni 2017; Nolan 2018).14 Part of a so-called ‘counterinsurgency’ war (Innes-Robbins 2016), these distinct villagization programs constituted Euro-American attempts to control the political liberation of colonies in Africa and Asia after WWII. Indeed, forced resettlement programs were simultaneously military and political projects, enmeshed with mechanisms from the post-WWII development project led by the United States, such as capitalist conceptions of land ownership and wage labor (Kwak 2015; Nolan 2018).

The combination of control with development was particularly clear, for instance, in the French program in Algeria and the British one in Kenya (Feichtinger 2017). The French ‘regroupement’ program, however, unlike the British program, did not target a particular ethnic group but rather the whole population of northern Algeria. ‘Regroupement’ was conceived as both a form of concentration camp and as ‘psychological action’, which meant the coordinated military deployment of propaganda, education, development, and police actions (Henni 2017). By 1959, this process had become a national development plan called the ‘plan de mille villages’ (Paret 1964). In Kenya, the British equally scaffolded their military campaign against the Kenya Land and Freedom Army as a national development plan, known as the Swynnerton plan. As in Algeria, the building of camps, self-built by the displaced, came with an array of development measures whose purpose was to ‘westernize’ rural Kikuyu to a limited degree (Nolan 2018), similar to the ‘assimilated stage’ in Portuguese colonies. Forced resettlement in Kenya amounted to little more than creating a violent and vast carceral landscape, reminiscent of earlier internment and concentration practices (Elkins 2005). Indeed, after liberation most camps in Kenya were abandoned. In Algeria, most ‘regroupements’ were transformed into villages (Feichtinger 2017); likewise, in Guinea-Bissau, many village-camps exist today as lively villages and towns. Despite serving different political ends, these programs employed self-building practices in a way that showed what police powers had in common with development, namely in the commitment to the dubious doctrine of ‘helping people to help themselves’ (Muzaffar 2007: 38).

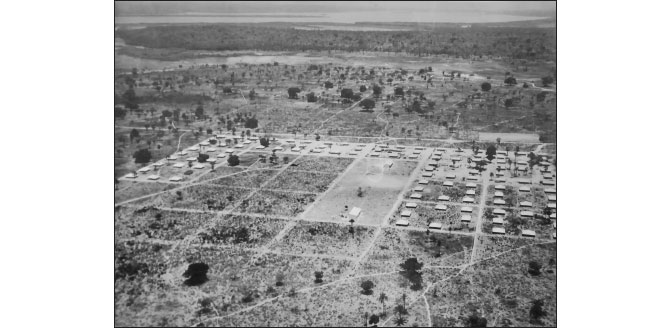

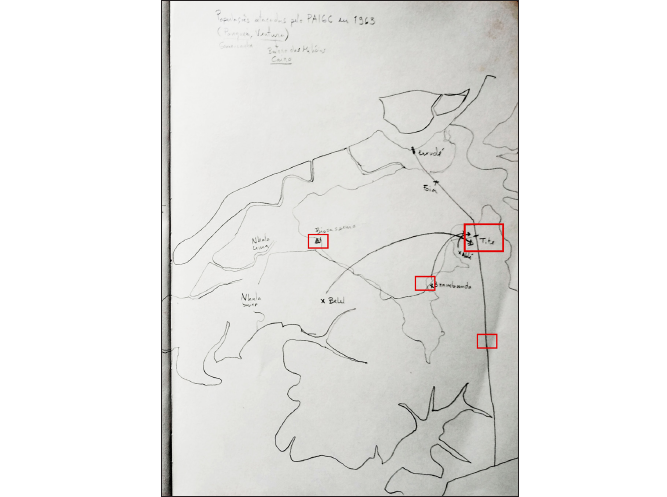

Coming at the tail end of this history, the programs in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau gave this war strategy yet another iteration combining landscape securitization and militarization with claims for development. The case of Guinea-Bissau was both the best illustration of this and an exceptional episode (Figure 15). There, following from Spínola’s war plan and villagization’s central role in it, the whole Portuguese military apparatus was re-organized as a national ‘development’ force. This was contrary to the situation in Angola and Mozambique, where forced resettlement was less nationally coordinated and represented and was more often used in a haphazard and sectorial fashion. In fact, Spínola’s war plan was a direct response to the strategy of Amilcar Cabral’s independence party, Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo-Verde (PAIGC), of winning independence by promoting Guinea-Bissau’s socio-economic development. The PAIGC combined military activity with the creation of infrastructure, such as markets and medical facilities, in the building of new villages for escaped Guineans, securing them education and food (Dhada 1993: 38).15

Presented as based on respect for Guinean culture and social organization, Spínola’s plan cast resettlement as a welfare program that promoted rural modernization. This was partly achieved by rationalizing the construction of ‘new villages’ and realigning its priorities to an expanded social and economic scope. It also answered the need for a more effective use of colonial troops and promoted the illusion of Guineans’ participation in national political affairs, namely through the People’s Congress. ‘New villages’ were intended to work as nodes of development throughout the country, ‘irradiating progress’ to surrounding settlements.16 Spínola called all this maneuvering ‘For a Better Guinea’ (1970). Of course, ‘new villages’ also retained their role as military police apparatuses and operational bases: most were either built in the vicinity of a colonial barracks or in its area of operations (Figures 16, 17). Particular to Guinea-Bissau, then, was how forced resettlement simultaneously came to articulate a nation-wide political vision of modernization, rural in nature.

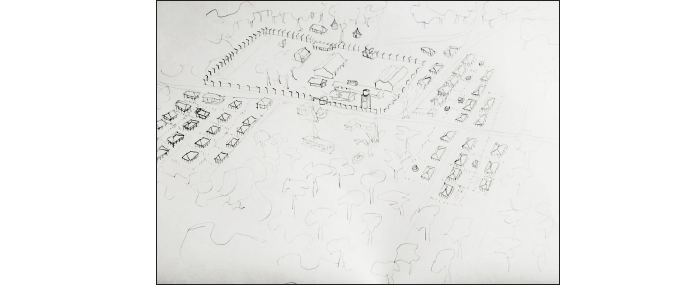

In a confidential military report of 1971 that planned ‘socio-economic maneuvres’ for the dry season of 1971–72, the military considered ‘as priority the fields of education, health, agriculture, roads and the urbanization of population centres’.17 The plan listed the construction of new roads, bridges, dozens of schools of the ‘villagization type’, and the construction of dozens of new settlements or camps (Figure 18). Civil colonial administration was responsible for some of these works and for managing private and social institutions, such as the Gulbenkian Foundation.18 Forced resettlement involved a wide array of colonial agents and concerted action at various levels, in effect becoming an apparatus to control rural populations and certain ethnicities while allowing the development of others. For instance, a key premise for the military operations of 1971–72 was to ‘intensify the motivation of the Balanta ethnicity with a view to accelerate the process of psychological unsettling that has been verified, improving villagization and its collective benefits and creating new villagizations in its respective territory’.19

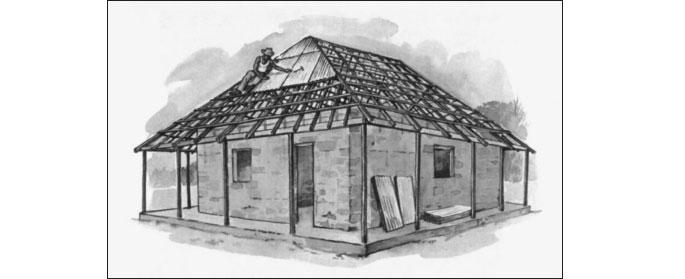

Drawing by Augusto Trigo of a ‘villagization type’ house, presented in the colonial primary school manual for Guinea-Bissau from 1972, O meu primeiro livro de leitura [My first reading book] (published in Portugal for the Government of the Province of Guinea), p. 15. Online at Memoria de Africa, Univesidade de Aveiro, http://memoria-africa.ua.pt/Library/ShowImage.aspx?q=/geral/L-00000012&p=1.

Without acknowledging it, Varanda (1968) supplied a succinct description of the villagization house model in his review of colonial housing schemes (Figure 19). His description and drawings were confirmed by recent fieldwork: the model house was a four-room rectangular plan, with a central corridor and a surrounding veranda. The houses were made of clay blocks, a timber roof structure, and either thatch or zinc panels for roofing, and were arranged in an orthogonal grid with roads wide enough for military vehicles to pass.20 Plot size, shape and number were drawn by the Portuguese military in coordination with a planning office in Bissau, headed by Spínola. Plots were then given free of charge to local chiefs to distribute among the different households, as an obvious attempt to reinforce colonial power and enrol local power brokers in the villagization mechanism. Every house had to be built by its future owner. Like the British and French programs, self-building was a crucial part of the process. The architecture of villagization was bare and stark in contradiction to the welfare and development colonial discourses eerily captured in the school manual of 1972 (Figure 18). It was also strangely similar to every colonial housing model that had come before, from Santa Luzia onwards. Why this was so is still up for debate; the original villagization designs remain to be found.

Study of a villagization scheme by Varanda (1968: 40).

The program was, after all, a military strategy that involved the forced displacement of people to controlled environments. Its welfare ambitions, particularly in Guinea-Bissau, partly obscure the fact that it was a violent endeavour. This does not mean forced resettlement did not produce landscapes of aspiration and opportunity. For ‘Idris’, a middle-aged Bissau urbanite working for the University Amilcar Cabral, resettlement was a welcome change.21 His family was made to move to a ‘new village’ in Sedengal, in north Guinea-Bissau. His father was a sepoy, or colonial police agent, and his uncle managed the local depot. He recalls how the bare ‘villagization’ houses were much better than their former houses. He also recalls daily life being ‘good’: there was food, education (from Portuguese military teachers), and order. His is the recollection of a child during the war, but it is shared by many other informants, most of whom were young adults in the 1960s.22 According to them, under the purview of social services and the attendant law and order, together with the opening-up of commercial activities with the metropolitan market, the ‘new village’ was a place for personal and collective growth. It constituted a form of urbanization. This did not mean that people rallied behind the Portuguese. On the contrary, many informants reported that many people maintained relationships with the PAIGC, the independence party, during their time living in the ‘new village’, and how happy everybody was when the Portuguese left.23 Forced resettlement was thus as much a coercive exercise of colonial control and violence as a co-produced landscape in which many Guineans expanded their possibilities and what it meant to be African within the luso-utopia. This is exemplified by the fact that most ‘villagization’ houses, during and after the war, were reinterpreted and transformed, not unlike Santa Luzia’s houses (Figure 20).

Field sketch illustrating how the original ‘villagization’ house of a female informant was transformed and enlarged, while keeping its architectural language, by removing its zinc roofing, letting the house ‘melt’ with the rains and then rebuilding a new one on top. Drawing by Rui Aristides Lebre, Tite, May 2023.

Final Remarks: To Dwell in the Luso-tropical Dream

Spínola’s ‘Better Guinea’, as well as its equivalents in Angola and Mozambique, lost the war. After 14 years of intense conflict in multiple fronts, and even with the most ambitious housing and development plan ever conceived by the Portuguese state, luso-tropicalism was finally defeated — or at least what stood as its concrete, imperfect, and ambiguous colonial reality. In fact, an entire rural world emerged out of this war for independence that beckons an attentive study, still to be developed. Nevertheless, this last episode of luso-tropicalism was its most brutal, leaving in the fields of Guinea-Bissau, Angola, and Mozambique evidence of the utopia’s world-creating power and simultaneous overwhelming violence.

The luso-tropical utopia of a pluri-racial colonial society played a part in setting the norms and forms of Portuguese colonial spatial practices in the mid-20th century, often in a close dialogue with ethnography and the notion of ‘cultural respect’. Scholars of architecture have interpreted this period as a highly innovative one, leading to the production of ‘tropical modern architecture’, argued as a progressive creative style that, unfortunately, had to navigate within a conservative regime (Tostões 2013; Milheiro 2012c). What is often forgotten in these accounts is that the luso-tropical utopia tied architecture discourses and practices to colonial apparatuses of extraction and to the asymmetrical governing of ‘indigenous’ and ‘civilized’. It also tied government strategies to architectural imaginaries that promised more than they could deliver. Well-intentioned urban proposals and designs, colonial modernizers, dreams of a Europe in Africa, all came back to the gritty everyday of governing a colonial political economy supported by the reproduction of extreme inequalities. Furthermore, most studies of late colonial Portuguese architecture fail to take into account the relational and co-produced nature of space (Pieterse 2008). If from Santa Luzia onwards we can observe an architectural creativity borne of an ethnographically informed sense of modernity, then we should equally be able to recognize how the richness of these architectures derive from Guinean agency. This richness derives not from the appropriation of Guinean forms and traditions by Portuguese architects and planners but rather from the actual work of Guineans in co-producing, building, and expanding those architectures, making them their own and part of the country’s present.

To return to the prime-time televised question of whether Portugal is a racist country, it is true that for most of its modern history Portugal ruled through a government apparatus that was as actively racist as the popular belief and perception about nation and history that supported it. By the mid-20th century, luso-tropical propaganda had glossed over the dictatorship’s racialized rule with a development discourse that gained a utopia. How much does this history of colonial government and feeling affect today’s forms and norms?

Last year, during a master’s defense in the University of Coimbra’s Department of Architecture, for whose jury I was a member, a student presented the design for a modern urban plan for Bissau. It proposed vast new housing quarters inspired by the Balanta people’s vernacular compounds presented in Mota’s survey (1948). When the jury questioned the selection of the Balanta ethnicity for a modern house model, the student replied that it was representative of most Guineans and thus their architecture encompassed the cultural variety of Guinea-Bissau. This formulation is highly problematic for a variety of reasons, one of which is the picking of one ethnicity over others and assuming its social structures are stable and translatable to other social dynamics. A debate then ensued that simply bypassed the fact that 70 years later, we were thinking akin to Portuguese colonial officers in 1948. Varanda’s critique was nowhere to be found, particularly his warning about failing to take the Islamic majority into consideration. A general amnesia hovered over the whole session and the discussion became heavy with postcolonial guilt and finger-pointing in the attempt to liberate the student from the complexities of Guinean history and society. The student received a top grade.

How much the racial structures of government and feeling seep into our present is difficult to address broadly, seized as it is by professional and collective amnesias on all sides. Looking into current architecture and urban planning practices, however, it is clear we are still within the luso-tropical horizon, if only in trying to harness that ‘tropical’ creativity from the 1950s and 1960s without facing its full history. This avoidance of the more violent and complex aspects of colonial history amounts to a silencing of subaltern histories, common to architectural historiography, that enables a direct reproduction of colonial inequalities in our present. There is, thus, a need to move beyond the simple rejection or acceptance of contrived ideological constructs such as luso-tropicalism and to recognise that the social-spatial situations brought about or involving the latter, as I have shown, make luso-tropicalism a critical lens by which to address the coloniality, racism, and injustice that exist today within spatial phenomena. To approach these phenomena, this paper argues, we should open architectural historiography to tentative subaltern histories and in the process welcome the possibility of more direct confrontations with historical legacies, while affording new readings into the entangled political and social effects of architecture.

Notes

- Emile Marini, Liste dês prises de que de la Guinée Portugaise à travers l’objectif du jornaliste Emile Marini, 1959. Source: INEP archive, folder A6/A12. James Fernandes, a Goan independent fighter and journalist called Marini ‘an unscrupulous mercenary, and had been commissioned by the Portuguese Government to write and publish in English newspapers favorable reports of the conditions in Goa’ (1990: 82–83). All translations are by the author. [^]

- Key exceptions are Milheiro (2012a) and Milheiro and Fiúza (2016). For a succinct history of Guinea-bissau, see Pélissier (1989). [^]

- Archival research was conducted in Lisbon’s Overseas Historic Archive, the national archive of Torre do Tombo, the University of Coimbra Historical Archive and Guinea-Bissau’s national archive of INEP (Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisa). Bissau’s INEP archive, having been raided during Guinea’s civil war (1998–99), suffered considerable damage and disorganization. Most documents cited from this archive have, therefore, incomplete references. Field work was conducted in a nine-day sojourn to Bissau in October 2019, a two-week field trip to the centre and south of the country in November 2022 and a month-long field stay in the town of Tite, south of Geba, in April and May of 2023. As part of the project RegRural, I was accompanied in the last of these field trips by the Cape-Verdian artist César Schofield Cardoso, in 2022 and 2023, and the historian Mustafah Dhada in 2023. [^]

- Beyond the colonial city’s perimeter, irregular streets grew from two avenues connecting the city to the military barracks and the airport, comprising assemblages of single-story, mostly mud-brick houses with zinc panels for roofs, more common after the late 1960s; before then, thatch was more common. [^]

- Opening speech of Sarmento Rodrigues at the second annual conference of colonial administrators, November 27 of 1947. Source: INEP archive, uncatalogued folder and document, p. 20. [^]

- In the first conference the permanent committee for CIAO was formed by Spanish archeologist Jose Martinez, Professor Théodore Monod from France’s IFAN, Paul Rivet from the Musée de l’homme, C. Daryl Forde from England’s International African Institute and the Portuguese anthropologist António Mendes Correia, director of the Colonial Superior School in Lisbon, then being reformulated for a ‘scientific approach’ to the colonies. [^]

- The urbanization plan used a financial scheme common to state-promoted housing in Portugal that supported individual proprietorship through a system of low mortgage payments. For an overview of housing policies in Portugal, see Agarez (2018). [^]

- I want to thank one of the anonymous reviewers for pointing out the importance of addressing the distinction between ‘introverted’ and ‘extraverted’ spaces and how these might constitute radically different experiences of urbanity. [^]

- Interview conducted with ‘Alberto’ on October 11, 2019. The name is a pseudonym to safeguard the anonymity of an informant who was kind enough to give me a tour of the house he and his family lived in, one of Santa Luzia’s original houses that his father had passed on to him. [^]

- Franz Boas (1858–1942) was a North American ethnographer credited with being one of the founders of modern anthropology. He had a central role in advancing the analytical concept of culture as autonomous from evolution and ‘civilization’. Because of Darwin’s influence in the 19th century, the study of culture was tied to the notion of internal evolution from simple to complex states of society, giving rise to the primitive-civilization duality. Boas’ treatment of culture as an autonomous historic category helped anthropology advance the study of ‘cultures’ as independent historic units, and thus to separate, even if only conceptually, the study of then called ‘primitive societies’ from their political subjugation by the ‘civilization’ of Europeans. For a critical study of this history see, for instance Stocking (1968) and Clifford (1988). [^]

- Numbers concerning the total population involved are sketchy at best and rely heavily on incomplete military and colonial records. [^]

- Document titled ‘Manobras Sócio-Económicas’ and dated August 5 of 1971. Source: INEP archive, folder titled ‘Diversos (Confidencial)’. [^]

- By 1968, Spínola was an eminent figure in the dictatorship, rallying behind him important political voices and sectors of the regime. After leaving Guinea-Bissau in 1973 he became an outspoken critic of the regime’s solution for the African colonies, offering his own, Gaullist-inspired, federalist solution for a revised pluri-continental nation. His fame and influence in the military and political establishment made him the first president of Portuguese democracy after the Carnation Revolution of April 1974. For a biography on Spínola, see Rodrigues (2010). [^]

- The complex genealogy of the ‘villagization’ programs include also the ‘strategic hamlet’ program by the US army in Vietnam in the 1960s, as well as the ones promoted by independent African nations, for instance in Ethiopia and in Tanzania’s well-known Ujamaa villages. [^]

- Flora Gomes’ feature film Mortu Nega from 1988 provides a vivid portrait of the functioning of the itinerant social services and liberated villages of the PAIGC, available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TNZ_4lczt5A&t=2393s&ab_channel=avurto, accessed on May 26, 2022. [^]

- War directive for 1968, no. 43/68, António Sebastião Ribeiro de Spínola (Brigadier). Source: Arquivo Histórico Militar (AHM), DIV2/4/226/1. [^]

- Document titled ‘Manobras Sócio-Económicas’, August 5 of 1971, p. 2. Source: INEP archive, folder titled ‘Diversos (Confidencial)’. [^]

- Idem, p. 7. As the war progressed, the military appropriated more and more of the so-called socio-economic measures, given the limitations of the colonial administration, whose budget and power extended very little outside the main urban centers. [^]

- Idem, p. 2. [^]

- INEP, confidential report of 1973, uncatalogued document, folder ‘Diversos (Confidencial)’. Zinc roofing became more common later in the war, often being associated with social progression by Guineans living in the ‘new villages’. [^]

- Interview conducted on October 9, 2019. The name used is a pseudonym to ensure the anonymity of the informant. [^]

- Interviews conducted with 12 informants in Tite between 22 of April and 8 of May, 2023, 3 women and 9 men, all aged between 15 and 20 years when they moved to the Tite camp, or the ‘new village’ called Tite, sometime between 1963 and 1969. [^]

- Idem. [^]

Author’s Note

This paper emerged from post-doctoral research developed between 2018 and 2021 at the Centre for Social Studies, Coimbra, under the guidance of Dr. Tiago Castela and Dr. José António Bandeirinha. It also draws on insights from recent field research conducted by the author in Guinea-Bissau during 2022 and 2023, as co-investigator in the research project Regulating the Colonial Rural (2021–2023). An earlier version of the paper was presented at the 17th biennial conference, Virtual Traditions, of the International Association for the Study of Traditional Environments (IASTE), August 31 to September 3, 2021. I would like to thank both my session colleagues (Session B6, Identity, Ethnicity, and Architecture) and the audience for the thoughtful comments that have much helped the development of the paper.

Research involving human subjects, human material or human data was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The identity of the research subject(s) was anonymised throughout the work. Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Agarez, R (ed.). 2018. Habitação: Cem Anos de Políticas Públicas em Portugal, 1918–2018. Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda.

Ágoas, F, and Castelo, C. 2019. Social Sciences, Diplomacy and Late Colonialism: The Portuguese Participation in the Commission for Technical Co-operation in Africa South of the Sahara (CCTA). Estudos Históricos, 32 (67): 409–428. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1590/s2178-14942019000200005

Almeida, MV. 2004. An Earth-Colored Sea: ‘Race’, Culture and the Politics of Identity in the Post-Colonial Portuguese-Speaking World. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Almeida, MV. 2008. Anthropology and Ethnography of the Portuguese-Speaking Empire. In: Poddar et al. (eds.), A Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literature. Continental Europe and its Empires. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 435–439.

Anderson, W, Roque, T, and Ventura Santos, R (eds.). 2019. Luso-tropicalism and Its Discontents: The Making and Unmaking of Racial Exceptionalism. Oxford and New York: Berghahn.

António, DS. 2008. Sarmento Rodrigues, a Guiné e o Luso-tropicalismo. Cultura: Revista de História e Teoria das Ideias, 25: 31–55. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4000/cultura.586

Barbosa, M. 2007. Spinola, Portugal e o Mundo: Pensamento e Acção Política Nos Anos da Guiné, 1968–73. Revista de Historia das Ideias, 28: 391–427. DOI: http://doi.org/10.14195/2183-8925_28_16

Bender, G. 1978. Angola under the Portuguese, the Myth and the Reality. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Carlos, J. 2020. Portugal Não É Um País Racista, Mas Existe Racismo Em Portugal. Deutsche Welle (DW), July 2: https://p.dw.com/p/3eh38 [accessed March 29, 2021].

Castelo, C, and Alves, VM. 2019. On the Distance Between the Colonial Situation in Mozambique and the Luso-tropicalism: Letter of António Rita Ferreira to Jorge Dias, with Attached Article. Etnográfica, 23(2): 417–438. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4000/etnografica.6964

Castela, T. 2010. Imperial Garden: Planning Practices and the Utopia of Luso-Tropicalism in Portugal/Mozambique, 1945–1975. Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Proceedings — Architecture, Tradition, and the Utopia of the Nation-State (238): 75–98.

Castela, T. 2018. Daydream Continent: Europe as a Space-Time Horizon in Architectural History. Architectural Histories, 6 (5): 1–7. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/ah.274

Clifford, J. 1988. The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth Century Ethnography, Literature and Art. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4159/9780674503724

Comissão para o Estudo das Campanhas de África (CECA). 2006. Resenha Histórico-Militar das Campanhas de África (1961–1974), 6th volume, Angola: Aspectos da Actividade Operacional, Tomo I, Livro II. Lisboa: Estado-Maior do Exército.

Dhada, M. 1993. Warriors at Work: How Guinea Was Really Set Free. Denver: University Press of Colorado.

Diniz, C. 2013. Urbanismo No Ultramar Português: A Abordagem de Mário de Oliveira (1946–1974). Master’s dissertation, ISCTE — Lisbon’s University Institute.

Elkins, C. 2005. Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Feichtinger, M. 2017. ‘A Great Reformatory’: Social Planning and Strategic Resettlement in Late Colonial Kenya and Algeria, 1952–63. Journal of Contemporary History 52 (1): 45–72. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0022009415616867

Ferguson, J. 2006. Global Shadows: Africa in the Neoliberal World Order. Durham and London: Duke University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9780822387640

Fernandes, J. 1990. In Quest for Freedom. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company.

Ferreira, JCN, and Veiga, VS. 1957. Estatuto dos Indígenas Portugueses das Províncias da Guiné, Angola e Moçambique. Lisboa.

Freyre, G. 1946 [1933]. The Masters and Slaves. New York: Knopf.

Fykes, K. 2009. Managing African Portugal: The Citizen-Migrant Distinction. Durham: Duke University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv123x6nd

Hansen, P, and Jonsson, S. 2014. Eurafrica: The Untold History of European Integration and Colonialism. London and Oxford: Bloomsbury. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5040/9781472544506

Henni, S. 2017. Architecture of Counterrevolution: The French Army in Northern Algeria. Zurich: GTA Verlag, ETH Zürich. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4000/abe.3105

Hodge, JM, Hödl, G, and Kopf, M (eds.). 2014. Developing Africa: Concepts and Practices in Twentieth-Century Colonialism. Manchester: Manchester University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7228/manchester/9780719091803.001.0001

Holston, J. 2008. Insurgent Citizenship: Disjunctions of Democracy and Modernity in Brazil. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9781400832781

Innes-Robbins, S. 2016. Dirty Wars: A Century of Counterinsurgency. Cheltenham: The History Press.

Kwak, N. 2015. A World of Homeowners: American Power and the Politics of Housing Aid. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226282497.001.0001

Lebre, RA. 2017. From the Organization of Space to the Organization of Society: A Study of the Political Commitments in Post-War Portuguese Architecture, 1945–69. Unpublished thesis (PhD in Architecture), University of Coimbra.

Macagno, L. 2018. As Ironias Pós-coloniais da Lusofonia: A Propósito De Um ‘Erro de Tradução. In: Cahen, M, and Braga, R. (eds.), Para Além do Pós(-)Colonial. São Paulo: Alameda, 223–234.

Mbembe, A. 2001. On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Meneses, MP. 2010. O ‘Indígena’ Africano e o Colono ‘Europeu’: A Construção da Diferença Por Processos Legais. E-cadernos (online), 7, https://journals.openedition.org/eces/403. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4000/eces.403

Meuser, P, and Dalbai, A (eds.). 2021. Architectural Guide to Sub-Saharan Africa – Volume 3, Western Africa: Along the Atlantic Ocean Coast. Berlin: DOM publishers.

Milheiro, AV. 2012a. Guiné-Bissau, 2011. Porto: Circo de Ideias.

Milheiro, AV. 2012b. À Procura de Mário de Oliveira: Um Arquitecto do Estado Novo. Jornal dos Arquitetos, (245): 24–37.

Milheiro, AV. 2012c. Nos Trópicos Sem Le Corbusier: Arquitectura Luso-Africana no Estado Novo. Lisboa: Relógio d’Água.

Milheiro, AV, and Fiúza, F. 2016. Urbanidades: Arquitecturas e Sítios Históricos da Guiné-Bissau. Lisboa: Mário Soares Foundation.

Mota, AT da and Neves, MV (eds.). 1948. A Habitação Indígena na Guiné Portuguesa. Bissau: Centro de Estudos da Guiné Portuguesa.

Myers, G. 2011. African Cities: Alternative Visions of Urban Theory and Practice. London: Zed Books. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5040/9781350218123

Nolan, G. 2018. Quasi-Urban Citizenship: The Global Village as ‘Nomos of the Modern’. The Journal of Architecture, 23 (3): 448–470. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2018.1460388

Nyce, R. 1973. Chinese New Villages in Malaya: A Community Study. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Sociological Research Institute LTD.

Muzaffar, I. 2007. The Periphery Within: Modern Architecture and the Making of the Third World. Unpublished thesis (PhD), Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Oliveira, M de. 1962. Urbanismo no Ultramar: Problemas Essenciais do Urbanismo no Ultramar — Estruturas Urbanas de Integração e Convivência. Lisboa: Agência Geral do Ultramar.

Paret, P. 1964. French Revolutionary Warfare from Indochina to Algeria: The Analysis of a Political and Military Doctrine. Princeton Studies in World Politics, 6. New York: F. A. Praeger.

Pélissier, R. 1989. História da Guiné: Portugueses e Africanos na Senegâmbia: 1841–1936. Lisboa: Editorial Estampa.

Pieterse, E. 2008. City Futures: Confronting the Crisis of Urban Development. London: Zed Books. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5040/9781350219199

Rodrigues, LN. 2010. Spínola: Biografia. Lisboa: Esfera dos Livros.

Sindicato Nacional dos Arquitectos (SNA). 1962. Arquitectura Popular em Portugal. Lisboa: SNA.

Spínola, A de. 1970. For a Better Guinea. Lisboa: Agência Geral do Ultramar, 1970.

Stocking, GW. 1968. Race, Culture and Evolution: Essays in the History of Anthropology. New York: Free Press.

Tostões, A. 2013. Arquitectura Moderna em Africa: Angola e Moçambique. Lisboa: Caleidospópio.

Varanda, F. 1968. Um Estudo de Habitação Para Indígenas em Bissau. Geographica, 15: 22–44.

Viegas, S de M, and Pina-Cabral, J de. 2014. Na Encruzilhada Portuguesa: a Antropologia Contemporânea e a Sua História. Etnográfica, 18(2): 311–332. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4000/etnografica.3694