Introduction

Post-war Hungary may seem the ideal place to develop a critical theory of capitalist society: the work of Georg (György) Lukács, the internationally acclaimed Hungarian philosopher whose 1923 book, History and Class Consciousness, was a major inspiration behind later neo-Marxist theories, offered a vantage point to assess the dominant ideologies. However, the authoritarian state-socialism of Hungary permitted only apologetic theorizations, using the Marxist critique of capitalist society and culture to justify its own form of domination. But even to philosophers of the Frankfurt School in Germany, the reality of authoritarian socialism was a challenge they refused to confront. Was a critical theory in state-socialist societies even possible? And if so, how did it affect the theory of architecture?

As in other state-socialist countries, architectural debates in Hungary between 1960 and 1990 displayed conflicting lines of thought. Typically, these conflicting tendencies each claimed a Marxist lineage for themselves, and their positions regarding architecture and planning were different. However, how firmly this critical theory was rooted in the ‘real’ Marxian tradition is hotly debated, as is the question of what constitutes orthodox Marxism. Although the debate, as we will see, was well-informed and critical, references to Western neo-Marxist thinkers, such as Walter Benjamin, Theodor W. Adorno, Manfredo Tafuri or Fredric Jameson, were conspicuously absent — as were references to Lukács himself.

Neo-Marxism and the Marxist Renaissance

In Hungary during the decades immediately after World War II, Marxism as official state philosophy became a rather ossified, schematic teaching that was present in statements of a few philosophers and intellectuals in key Party positions but that could hardly reach society at large. Ironically, it was the Hungarian uprising in 1956 that forced intellectuals to address the question of a critical, Marxist analysis of the social situation — something the ruling regime desperately wanted to avoid. A younger generation emerged, unburdened by the repressive atmosphere of the early 1950s. They were more inspired by the writings of Western, mostly French, Marxists such as Roger Garaudy, Henri Lefebvre and André Gorz than by texts written in state-socialist countries. They maintained ties to their counterparts in the East and West. The most important areas of this ‘Marxist renaissance’ were critical sociology, economic theory, aesthetics, film and literary theory.

In the Hungarian context, the most important driving force of a Marxist renaissance, Georg Lukács, was a controversial figure in the Communist Party. Around 1950, his theories of class struggle and democracy had been criticized as revisionist. After 1956 he was even arrested because of his support for the upheaval. He was able to rejoin the Party in 1967, as the earlier attacks by the Party had slowly ebbed, and a group of young philosophers, called the ‘Lukács school’ or ‘Budapest school’, gathered around him, working mainly in the fields of Marxist ethics and aesthetics. Among architects, however, his authority was badly damaged, mainly because of his earlier, prominent role in the introduction of socialist realism, and his critical exchange with the architect and theorist Máté Major, who was widely respected by his colleagues.

Máté Major, Georg Lukács and the Big Debate

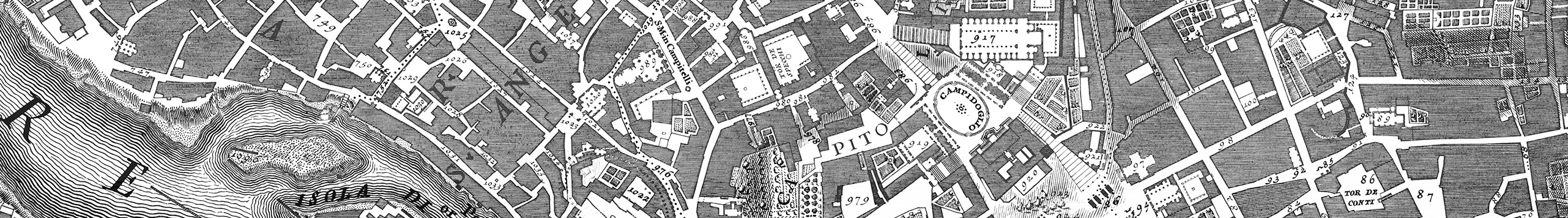

Máté Major, a former CIAM member turned Marxist academician, played a key role in the network of East-West exchanges in Hungary during the Cold War period. Major was the chair of the architectural history department (later the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture) at the Technical University Budapest, and head of the editorial board of the journal of the Union of Hungarian Architects, Magyar Építőművészet [Hungarian Architecture]. He was also the editor of Architektúra, a series of architectural monographs dedicated almost exclusively to the work of architects of the modern movement: Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer and Adolf Loos, but also of Aris Konstantinidis, Ernő Goldfinger and Pierre Vago — architects, some of them of Hungarian origin, whose work had not been published in monographs before (Figure 1). Several of the books in the series, with covers designed in the tradition of the Hungarian avant-garde, were written by Major himself. One of the monographs, by Eszter Gábor, discussed the history of the Hungarian CIAM group, of which Major was a member between 1933 and 1938 (Gábor 1972). Several of the books were translated and published in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and in Poland, and were appreciated throughout the East European countries, where books on architects of the Modern Movement were scarce. The books and journals in Major’s library, with hand-written salutes from well-known architects and critics around the world, including Bruno Zevi, Richard Neutra, Johannes H. van den Broek and the Serbian modernist Nikola Dobrović, indicate that he was well connected with architects and critics internationally.

In 1933, when Major joined CIAM, he also became a member of the Hungarian Communist Party, which was then an illegal organization. He was picked up in Budapest by Russian soldiers in January 1945, in the final days of World War II, and taken to the Soviet Union as a prisoner of war. It took his Party comrades almost a year to effect his release and enable him to return to Budapest (Major 2001: 13). There he was to play a central role in the Communist transformation of architectural culture. In a Communist Party brochure published in 1946, titled Építs velünk [Build with Us], just as on the cover of the periodical Magyar Technika [Hungarian Technology] the following year, we see Major sitting at a drafting desk, holding a compass: the archetype of the young, Communist technical intelligentsia. He filled key positions in a number of organizations and institutions, including the Ministry of Building. In 1948, he was awarded a doctorate, and the Party appointed him professor of architecture at the Technical University Budapest, and chair of a newly created institute. He started teaching a course that introduced students to questions of the profession, the fields of architectural knowledge and the role of the architect in society, and later also taught, reluctantly, the history of architecture.

After the successful Communist seizure of power in 1949, with the successive elimination of all political opponents (known as ‘salami tactics’), Major established himself as the key expert of post-war architectural reconstruction. However, by 1951 there could be no doubt that architectural reconstruction in Hungary meant Soviet-style socialist realism. This posed something of a problem, given that Major had consistently criticized the ‘formalism’ of socialist realism in his articles published between 1949 and 1951. József Révai, the minister of culture and the main ideologist of the Party, masterminded an elaborate and interesting plot. Architect and urban theorist Imre Perényi, who grew up and studied architecture in the Soviet Union before the World War and returned to Hungary in 1945, was commissioned to set off a debate with his article ‘Western Decadent Tendency in Contemporary Architecture’ (Perényi 1951: 7–16). Major responded with his text ‘Confusion in our Contemporary Architecture’ (Major 1951: 17–28). On April 17 and 24, 1951, the office of the Central Committee of the Party responsible for cultural policy organized in the Party headquarters a ‘debate on the present situation of our architecture’ (this was the official title), which came to be known as the ‘Big Debate’. It was chaired by Márton Horváth, member of the Political Commission of the Communist Party, and the final verdict was declared by Révai. On the podium, Major defended the cause of modern architecture, while Perényi argued for socialist realism. Well-known artists, architects and architectural and art historians, such as Tibor Weiner, György Kardos, László Gábor, Aurél Bernáth, and Frigyes Pogány, were invited to participate in the discussion. Among them was Georg Lukács, who was facing strong Party criticism at the time because of his alleged revisionism. Major, who perhaps did not realize that he was playing in a well-choreographed piece, was to defend the position of modernism, while the magniloquent Lukács had to demonstrate the falsehood of his arguments. The statements of the protagonists thus should be interpreted against the backdrop of the darkening political horizon.

Perényi accused the international, ‘cosmopolitan’ style of being a tool for imperialist states to infiltrate socialist culture, and called for a relentless struggle against such attempts. Major, the next speaker, began by outlining scientific and technological developments after the industrial revolution and their consequences for the urbanization process. He argued for the rational analysis of human needs, and rejected any concealment that would hide the eloquent face of architecture, which was to reflect the purpose of the building. ‘Real architecture finds the most appropriate, most aesthetic proportions, slight refinements to the scientifically resolved task, that increase the usability of the object — i.e. the building — to perfection’ (Bonta 2008: 132; translations by the author unless otherwise indicated). He also argued for standardization, prefabrication and the mass production of affordable housing. He further thought that socialist realism in the Soviet Union was an experiment still in an early stage, not a result to be implemented elsewhere.

In his first contribution to the Big Debate, Lukács accused Major of equating aesthetic quality with functionality. This false equation proved that Major could not distance himself from Western bourgeois decadence, claimed Lukács:

Everybody stayed at horribly ugly hotels, with excellent rooms. I know many beautiful old houses that cannot be inhabited the way we wish. It is the specificity of the aesthetic that it surpasses the mere conceptual fullness and correctness of the content. … A good poem has an aesthetic surplus over the mere content. We are making incorrect judgements in questions of architecture if we disregard this aesthetic surplus — as Major does, influenced by Western decadence. (Major 1981a: 37)

Major responded that Lukács failed to recognize the specificity of architecture as a consequence of its embeddedness in the conditions of production. He criticized the philosopher’s separating the functional and aesthetic sides of architecture instead of pointing out the dialectical relationship between them. It was unworthy of a Marxist to investigate and explain phenomena while disregarding their ontological differences: ‘Comrade Lukács — not unlike the creators of the Neue Sachlichkeit — lumps architecture together with painting and sculpture, and I assume that he judges them all from the position of literature’ (Major 1981a: 41).

Révai, the Party’s chief ideologist, rejected Major’s genealogy of modern architecture, arguing that he falsely traced its origins back to the Industrial Revolution, rather than to the crisis of capitalism after World War I and the defeat of the workers’ revolutions. Modern architecture in the service of the people is a false claim, Révai stressed: at best, it is a decadent luxury for the well-to-do, and a reformist utopia for the masses. He also criticized Major’s rejection of the architectural forms of previous ruling classes:

It is wrong that the architecture of class societies solely demonstrates the power and hegemony of the ruling class …, it can express certain progressive aims of those societies as well. It can develop forms that are not tied to the ruling class of a society, but survive it to serve the needs of the ones following it. (Révai 1951: 57)

Révai did not advocate copying forms from the past, or Soviet models — rather, it was the task of the architects to find out how to use such precedents, and how to avoid mistakes made by Soviet architects in the early phase of their pioneering work.

According to the account of the architectural historian János Bonta, who attended the event, Révai’s well-argued speech convinced many in the audience (Bonta 2008: 137). Major, following the party ritual of self-criticism, had to admit his mistakes. Consequently, he had to step down as dean of the Faculty of Architecture and as editor of Építés-Építészet [Construction-Architecture], a journal that supported socialist realism but also published modern examples. However, he was able to keep his professorship at the Technical University, and with a team of historians at his Institute, Major started work on a Marxist history of architecture, published in three volumes between 1954 and 1960. Although later a revised version and even a German translation (Geschichte der Architektur) were published, the book was not based on new research, but rather on a compilation of already published knowledge (Major 1974–1984). Major wrote a largely descriptive text, without taking a clear stance. The concluding sentences about modern architecture in the West are telling in this regard:

It is not the task of this book to answer all important theoretical questions. The architecture of capitalism is still developing and produces results which can be used in the further investigation of the concepts of design. The precise definition and the correct assessment of those achievements of the new architecture of capitalism, that serve the future, will be the task of future research. (Major 1984: 464)

For readers in Hungary, and East-Central Europe in general, this volume was one of the first available sources on the history of modern architecture. For the reviewer of Architectural Design, however, Major’s History of Architecture represented ‘the heap of flotsam of Western knowledge’ that showed how ‘polite learning can simply atrophy behind the Iron Curtain’ (Plommer 1975: 254). Nevertheless, Major’s reputation among architects as an ‘honest’ member of the nomenclature rose as the result of his defence of modernism — still more after his support for students of the Technical University who participated in the 1956 uprising, for which Major was later reprehended by the Party and attacked by some of the younger, career-hungry colleagues of the faculty.

Reassessing Modernism and Socialist Realism

In 1967, Akadémiai Kiadó, the publisher of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, published a small booklet by Major in the series Korunk tudománya [Science of our time], with the title Az építészet sajátszerűsége [The Specificity of Architecture] (Figure 2). It compares well to Tafuri’s Progetto e utopia (1969), which was written around the same time, in its modest size and high ambitions. The first half of the book is a series of case studies of the Parthenon, the Colosseum, the cathedral of Amiens, the chateau of Versailles and Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation in Marseille; the second is a theoretical reflection based on the examples: ‘problems in the form of a conclusion’, to paraphrase Tafuri.

It is the unresolved contradiction of form and function that moves architecture forward, emphasized Major. He regarded the Unité d’habitation as a building of high quality, fulfilling material, functional and cultural demands. He detected, however, an unresolved contradiction between future-oriented mass production technologies that were open and flexible and the ‘closed’ system used by Le Corbusier in Marseille. But the gravest of contradictions, according to him, could be seen in the countries building socialism in the decades after 1930. It was based on a misunderstanding of the essence of modern architecture. Ideologizing the lack of an industrial infrastructure to realize modern constructions, it was erroneously assumed that the art and architecture of socialism could be realized immediately, before economic-social transformation, and so had to differ from capitalist art and architecture. Therefore, modern architecture had to be rejected in the fifties as ‘cosmopolitan’ and ‘decadent’, and classicist and Renaissance forms had to be used in what was called the ‘progressive tradition’. This false theory, stated Major, produced worse buildings than ever before: while old architecture was able to express its age, Stalinist architecture only showed that big mistakes could be made in the name of Marxism, if the specificity of architecture remained unrecognized. He criticized socialist realism as the main example of this contradiction. However, he carefully avoided the term socialist realism, using ‘New Archaism’ and ‘New Eclecticism’ instead. The false form of these buildings distorted their content. Behind the palatial facades of the blocks were hidden small and poorly equipped flats, denying the ideal of equality of citizens and hindering the development of the forces of production, of materials, of construction and the technologies necessary to fulfil the demands of mass housing — a basic goal of a socialist society.

In this essay, Major’s intention to counter Lukács’s arguments in the Big Debate is quite clear; the title of his book, The Specificity of Architecture, lends a clue. Lukács’s major contribution to Marxist aesthetics was the book Die Eigenart des Ästhetischen [The Specificity of the Aesthetic], which had been published in Hungarian two years earlier, in 1965 (Lukács 1981). In this book, Lukács claimed an ontological Eigenart, a normative specificity for aesthetic phenomena. Major, in his book, emphasized the material aspects of building (constructions, machines, technologies) and the necessary knowledge as the basis of architecture’s specificity. In Marxist theory, insisted Major, the Produktionskräfte (forces of production) have no direct relation to the superstructure. He thus proposed a concept of autonomy based on a ‘true’ rather than ‘opportunistic’ interpretation of Marx. On the other hand, he also adhered to Lukács’s notion of the cognitive value of art by mirroring social reality, as well as the notion of the duality of form and content. Despite his forced self-criticism after the Big Debate, he must now have been convinced that his early suspicion, that Lukács disregarded architecture’s specificity, was correct after all. Still, in the book he made no reference to the debate or to Lukács. His intention was to demonstrate that contradictions between content and form are the driving forces behind the development of architecture.

Georg Lukács and the Marxist Renaissance

In the year that Major’s book The Specificity of Architecture was released, another — and in its conclusions, very different — reassessment of socialist realism was in the making: a two-volume anthology on socialist realism that was finally published in 1970 (Figure 3). The editor, the literatary theorist Béla Köpeczi, was an academic like Major himself, with a comprehensive knowledge of Western theories. He studied during the late 1940s at the Sorbonne in Paris, and became the leading official in charge of the publication policy of the Hungarian Communist Party, deciding what should be supported, banned and tolerated, in line with the cultural policy of the Kádár era (named after the secretary-general of the Communist Party, János Kádár). The two volumes of the anthology, almost 1,000 pages long, comprised hundreds of texts, starting with Charles Fourier, and included excerpts from writings by Louis Aragon, Ernst Bloch, Bertolt Brecht, Paul Eluard, Luigi Visconti, Roger Garaudy and many others, ending with a late essay by Lukács from 1965, ‘Socialist Realism Today’.

Lukács’s essay, originally written for the popular literary review Kritika [Critique], opened with the statement that the central problem of contemporary socialist realism is the critical re-evaluation of the Stalinist period. The main example discussed by the philosopher was Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s short novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962). He chose this text because it dealt with the problem of humaneness in times of Stalinist terror. In the final paragraph of his essay, he noted:

This is the eve of a Marxist renaissance in the socialist world. The re-birth is not only aiming at the correction of the distortions under Stalin, but first of all at grasping the new facts of reality using the old-new methods of Marxism. Certainly, to continue what was called Socialist Realism in the Stalinist period would be hopeless. But I believe those who want to bury Socialist Realism are wrong … and Solzenitsyn’s novel is showing us the way. (Köpeczi 1970: 441)

Béla Köpeczi, in his introduction to the anthology, underlined Lukács’s concept of humanism as a political strategy to attract bourgeois humanists who did not accept socialism, but who were ready to fight against fascism. Lukács was indeed the first protagonist of a ‘Marxist humanism’, having already written his Struggle Between Humanism and Barbarity during the war years in the Soviet Union (Lukács 1985). Köpeczi pointed out that this position had been rejected by such advocates of an ‘agitational art’ as Bertolt Brecht. Köpeczi, however, was convinced that socialist realism could express the greatest human values, if it were developed further on a progressive and innovative rather than a conservative basis. ‘It is innovative art that will attract the public and therefore, it will shape society’ (Köpeczi 1970: 60).

Marxist humanism as a programme was embraced by the critical opposition in Hungary. The ruling elite in state-socialist countries considered Marxism a ‘world view’ that made it possible to observe and explain reality by using a certain set of principles. This contemplative Marxism had no use for social criticism. To begin a discourse criticizing this state of affairs, one had to be very careful and avoid any direct confrontation with the system. The early work of Marx, first discovered in the 1930s, proved very useful in developing the tools and language of this criticism. Based on these early texts, an image of Marx as a ‘humanist philosopher’ had been constructed, in contrast with earlier interpretations. The protagonists of Marxist humanism regarded safeguarding social peace and avoiding an open confrontation with the communist regime to be necessary preconditions for their critical discourse (Vázsonyi 2014: 37).

Since the 1950s, Lukács’s ideas had been centred around the problem of everyday life, which had to be understood ontologically. Another important philosopher in this respect was Ágnes Heller, a member of the Lukács school who was also influenced by Jean-Paul Sartre. For Heller, humanism meant opposition to a ruling Party apparatus interested only in maintaining its privileges. She argued against determinism and for a Marxist ethics based on the relative autonomy of human action: ‘when the individual chooses between alternatives and places the imprint of his own individuality on the fact of choosing … he is exercising autonomy’. Being able to choose among different options is the precondition of freedom (Heller 1984: 22). This theme of everyday life also interconnects Heller’s work with that of Henri Lefebvre, to whom she referred in the opening pages of her book A mindennapi élet [Everyday Life], (1970), when discussing the alienation of the individual in everyday life (Heller 1984: 18).

Re-Humanizing Architecture

Opening, openness, humanizing: these were catchwords not only for critical Marxist voices, but also — for different reasons — for critical voices in architecture, eagerly taken up by Team 10 architects. Jaap Bakema spoke of the ‘open society’ as a notion able to absorb a range of different meanings, an approach free of ideological constraints. The Polish architect Oskar Hansen advocated ‘open form’, and Alison and Peter Smithson used the term ‘open society’ explicitly in connection with their Berlin Hauptstadt competition project in 1957–58. In architecture, the call for ‘re-humanizing’ was meant to envision other modernisms and to resuscitate neglected community life in the big city (Moravánszky 2017). There was thus quite an overlap with the ideas of Marxist humanists.

Magyar Építőművészet, the journal of the Union of Hungarian Architects, was redesigned in 1962, in line with this call. The first issue of the year came out with a cover that announced a new direction. Instead of the Soviet-style imageless covers with antiqua letters of the socialist-realist period, the organic pattern of a leaf with its fine system of veins was understood as a clear alternative to the grid — the organizational model and emblem of the International Style. For the new graphics editor, the architect Elemér Nagy, Alvar Aalto’s plea for an ‘elastic standardization’, with the much-quoted example of magnolia flowers, was an important source when looking for images to capture this new spirit: to maintain the modernist goals of efficient mass production, but to endow them with the potential for individual variation (Aalto 1940: 15).

In the same year, 1962, a large part of the fourth issue of Magyar Építőművészet was dedicated to Team 10 and the work of architects related to the group. Károly (Charles) Polónyi, who was in charge of this part of the journal, knew them personally, as he had attended the CIAM conference in Otterlo in 1959. Polónyi was invited to participate at the meeting on the suggestion of József Fischer, one of the most outstanding figures of Hungarian modernism and, like Major, a CIAM member — but unlike him, a Social Democrat, and thus with no chance of getting a travel permission, despite all the efforts on his behalf by Sigfried Giedion. At the conference, Polónyi presented his plans for the development of the south shore of Lake Balaton in West Hungary. During the fifties, the need for recreation facilities on the lake grew. In 1957, a managing committee for Lake Balaton was convened, with two stations, one on the north and one on the south shore. Polónyi was appointed chief planner of the south shore of the lake, with the task of developing a master plan for the region. The significance of this technical expertise, supported by abundant analytical material and local knowledge, remained the basis of Polónyi’s work after his Balaton assignment (Moravánszky 2015).

An interesting document regarding the ‘re-humanization’ of architecture was the small, well-designed book by Pál Granasztói and Károly Polónyi, Budapest holnap [Budapest Tomorrow], published in 1959, in the year of the Otterlo conference. The theme of the book was the reconstruction of the destroyed capital; the authors criticized the planning practices of the authorities. Cities are made by their inhabitants and not by plans, they wrote: ‘The construction and the beauty of a city is not only dependent on plans and regulations, but first of all on the force and will of its people’. Such statements differed radically from the rigid planning of town administrations and specialized big state firms.

In his autobiography, Polónyi remembered that his career as a designer in Hungary came to a halt when a Communist Party official made it clear to him that without Party membership, he had no chance of landing larger commissions (Polónyi 2000). Since he did not want to leave Hungary for good, like many other like-minded professionals, he opted to work in the so-called Third World, working from 1963 to 1969 for the Ghana National Construction Corporation and for Kumasi University of Science and Technology.

Critical Sociology and the ‘Étatist Elite’

Meanwhile, in Hungary, other intellectual fields contributed to the discussions on architecture and urban planning. In Hungary, sociology and social philosophy were the fields where theorists of the Marxist renaissance attracted a wide audience. Monthly journals such as Valóság, Új Irás, Kortárs, Mozgó Világ and Kritika regularly published critical essays that were read and discussed by architects. András Hegedüs, who headed the Social Research Group of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, formulated the goal of critical sociology clearly:

It is the task of sociology to analyze the alienation process of society, to show its causes and to contribute to its elimination or at least to its mitigation. It is therefore not the task of sociology to optimize the functioning of the state apparatus, but to serve the humanization of social conditions. (Vázsonyi 2004: 38)

Many critical sociologists focused their research on the urbanization process and the agricultural village, as well as the development and problems of the socialist-realist new town, Dunaújváros, the theme of a book by Miklós Miskolczi (1980).

György Konrád was one of the intellectuals who gained attention by conducting social research and casting the results in literary form. He studied literature and sociology at Budapest University in the years before the uprising of 1956. From 1959 on, he worked for seven years as a children’s welfare supervisor in Budapest’s 7th district. His experience with poverty and social decay served as the basis for his novel A látogató [The Case Worker, 1969]. The novel revealed the poverty, loneliness and despair of a part of the population for the first time in literary form, and described the dilemma of the social worker, a state employee, facing this situation. The small book was a huge success among critical intellectuals, and sold out in days. In 1965, Konrád joined the Városépítési Tudományos és Tervező Intézet [Institute for Urban Science and Planning] in Budapest. He worked closely with urban sociologist Iván Szelényi, with whom he published the book Az új lakótelepek szociológiai problémái [Sociological Problems of the New Housing Estates] in 1969. The book summarized the results of the empirical research the authors conducted in four housing estates, investigating the social composition of their population, their economic and cultural position, the social organization (family, household, services, ties between families) and the evaluation of the estates by their inhabitants, using an elaborate system of questionnaires. The results showed that the distribution system consistently benefitted families ‘of the higher social strata, better educated and with higher income’ (Szelényi and Konrád 1969: 138). The authors indicated the dangers of this development:

[The] housing shortage is now the most neuralgic point of tension of our social life. Families who would be ready to pay a large part of their income for better living conditions, but who are unable to fit into the rigid financing schemes, will despair and this desperation can trigger many social problems and disorganization. Work ethics decline, the stability of families is endangered, and the inequality in terms of the education of children rises. (Szelényi and Konrád 1969: 140)

In conclusion, Szelényi and Konrád urged for a more differentiated system of housing production, financing and distribution.

In the 1970s the political horizon darkened, particularly for Marxists in the opposition. With Lukács’s death in June 1971, the last obstacle to disciplining rebellious Marxists had been removed. After formulating the new Party position in May 1973, key figures of the Marxist opposition were removed from state research institutes. Their options were either to surrender or to accept marginalization. Accordingly, this group split in two: one group, which included Konrád and Szelényi, left the country, accepting scholarships or faculty positions at Western universities. The others withdrew from political life, taking up an apolitical rather than oppositional stance, insisting on ‘pure theory’ and accepting the rules of the game. Later, they formed the so-called ‘democratic opposition’ that rose into political power after the fall of state socialism. Polónyi noted, ‘At the same time I also felt I had to go, because the reform movement changed to empty rhetoric. So I returned to Africa’ (Polónyi and Konrád [2000?]: 9).

Szelényi and Konrád wrote their next book, Az értelmiség útja az osztályhatalomhoz [The Intellectuals on the Road to Class Power], in 1974 in Hungary, but the communist regime accused the authors of inciting hate against the system. The manuscript was confiscated by the police, albeit one copy was smuggled out of the country and published in Germany (Konrád and Szelényi 1979). The thesis of the book was that the intellectuals strove for political power, legitimating this claim by their knowledge. The social function of expert knowledge is hegemony: ‘The intellectuals legitimate their claim to power with their knowledge. What matters is not the knowledge that is functionally necessary, but the legitimation of power’. It was a provocative proposition indeed, even more so as it was underpinned by a Marxist, even Lukácsian, theory of class struggle and class consciousness. Szelényi and Konrád considered the book a contribution to critical theory, applying the method of immanent critique to point out how étatistic positions had already infiltrated Marxism in the nineteenth century, and how this technocratic ethos motivates intellectuals to envision a scientifically organized society, betraying workers’ interests.

The claim of the authors that workers were powerless and that they were the most underprivileged class in Socialist Hungary was unacceptable to the Communist Party. Many of the criticized middle-class ‘intellectuals’ rejected it as well, since they felt weak and deprived of power. However, as the former ruling elite of Party bureaucrats began to erode, a new role in shaping a future society was clearly on the horizon for critical intellectuals, raising questions of their ideological commitment. By the 1980s, the gap was widening between bureaucrats, whose days were numbered, and a well-educated intelligentsia as the leading force of social transformation.

At this time, the positions of our protagonists were taking on new connotations in the political force field. Major, particularly because of his attacks against postmodernism, which were spreading quickly among architects and architectural students, was regarded increasingly as a figure of the old Party nomenklatura, unable to distance himself from academic Marxism. Konrád and Szelényi, while still in Hungary, were part of the ‘democratic opposition’ emerging from the camp of the Marxist renaissance. They were marginalized intellectuals and therefore able to articulate the interests of the workers. They regarded Polónyi, who never considered himself a Marxist, as part of the technobureaucratic elite ‘on the road to class power’, disconnected from the direct producers.

Polónyi described planning in his autobiographical texts as an ‘opportunistic profession: you have to take the opportunity’, and characterized the planner as a sailor ‘who should sail with the wind, instead of trying to alter the wind’ (Polónyi and Konrád [2000?]: 3). Konrád rejected this:

I have a horror when my very nice colleagues … with good intention, were standing on these models … and said ‘fifty thousand people on this estate, the tubes here and there’: they acted as the Gods. I felt that this superiority is just a kind of abuse. (Polónyi and Konrád [2000?]: 3)

However, he and Szelényi expected that the unfolding of étatism would eventually lead to the formation of a civil society able to articulate and handle conflicts.

In 1971–72, Oswald Mathias Ungers invited Jaap Bakema, Shadrach Woods, Reima Pietilä, Charles Polónyi and Alison and Peter Smithson to Cornell University to participate in his Team 10 seminar. Polónyi recalled that Szelényi, who was teaching at the time at Cornell, invited him:

to work with him on the field of social criticism. But at that time, I was working on another problem: in five years, we had to build as many houses as we could. Because another social fact was that back then many apartments were occupied by 2–3 families, without sewerage, without water. So, I was much more interested in using the available means as effectively as possible. So, at that time I did not agree with their criticism. I considered it an intellectual criticism that was based more on foreign literature than on real problems. (Polónyi and Konrád [2000?]: 6)

The gap between Polónyi’s pragmatic orientation and Konrád’s critique is evident in their ways of handling the high demands that mass production put on architecture in Hungary, increasingly turning it into a technical and scientific discipline by the late 1960s. The first issue of Épités–Építészettudomány [Building and Architectural Science], the periodical of the Department of Technical Sciences of the Hungarian Academy of Science, was published in 1969, with Máté Major as editor-in-chief. In his preface, Major mentioned architectural theory (including criticism), architectural history, building science and urbanism as the four areas of the discipline (Major 1969: 3–4). While socialist realism was concerned with architecture as an art, the pendulum now swung in the opposite direction: the mass production of buildings became the focus of new research, using the most advanced technologies available. With reference to Marshall McLuhan and Abraham A. Moles, whose works appeared in Hungarian translation, information theory was applied to develop an efficient system of industrialized building. Discarding the architectural drawing, the so-called ‘blind fabrication’ relied on a three-dimensional system of numeric coordinates, on which the production and assemblage of building parts was based (Gábor and Párkányi 1979). Hungarian theorists of standardization called for ‘the application of the Gutenberg principle’ (Gábor and Párkányi 1979: 15) (a reference to Marshall McLuhans’s book The Gutenberg Galaxy of 1962). They were convinced that mass prefabrication could benefit enormously from the introduction of computers. After the collapse of communism, the international success of the Hungarian firm Graphisoft, which had developed the ARCHICAD architectural design software, was based on this early research, which was originally intended to streamline the mass production of standardized housing units built of concrete slabs. Polónyi had already participated in a joint summer conference on the use of computers in the university, organized by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Technical University, Berlin, in 1968 (see proceedings in Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Technical University Berlin 1968).

Konrád considered such ‘étatist’ strategies as tools of oppression:

We believed that the big estates were perfect tools to make the people more apathetic, to transform them into some kind of machines. And the system to distribute them as some kind of premium, where people got their apartment as a present, was not good. It made the people like children. It was the self-confidence of the industrial vision of the scientific, technological revolution, and this whole futuristic rhetoric, and it was generally related to a socialist planification system in the East and capitalistic progress in the West. We wanted somehow to avoid the violation of city life and of the organic growth of cities. It was a period in which we wanted to show what people really wanted. The message was: please don’t intervene so much. Less state, more society. Less planification [sic], more surprising and unpredictable city life. Less rigid rationalism, more communication. Sensual communication: people should have all kind of opportunities to come together. (Polónyi and Konrád [2000?]: 8)

In an essay published in the popular social-science review, Valóság [Reality], Polónyi referred to this criticism to raise the question:

How should we proceed? It is obvious that the étatist planned economy must be maintained. Not only in socialist countries, where the conditions characteristic of capitalism no longer exist and cannot be restored, but even under capitalist conditions. Urban design has acquired a regional and national scale, and because the Earth’s resources are limited and shared, after all, the scale of urban design must be extended to encompass the whole Earth, turning it into an orbistic surface. This will only be possible through state and even international institutions, using instruments of state control. (Polónyi 1981: 70)

However, the ‘étatist elite’ cannot take responsibility for all manifestations of life; decisions on a range from the local to national scale have to be taken at the appropriate level. Polónyi warns against leaving such decisions to the market, as this would result in segregation: ‘This would exclude huge masses from the possibility of having an apartment, since the banks only give credit to those who belong in one way or the other to the prosperous’ (Polónyi 1981: 71).

This statement and the notion of an ‘étatist elite’ closely reflected Polónyi’s own view of himself; he was critical towards both the Party state and market capitalism: ‘Our aim was to use the opportunity. If we had not used the opportunity, one quarter of the population would now live in slums’.

The End of the Virgilian Dream

In the 1980s, as the cultural climate turned milder again, the tension between fractions of the opposition grew. Polónyi’s earlier concerns about the touristic development of Lake Balaton were transformed into an ecological issue. Triggered by a project to build a dam on the Danube, environmental protection became a central issue around which a large part of the opposition rallied. In 1983, Polónyi started a series of international summer schools (the International Workshop Seminars) on Lake Balaton and on the Danube, where his Team 10 friends Alison and Peter Smithson were regular guests (Figure 4). The first two took place in 1983 and 1985 on the Danube in the town of Ráckeve, focusing on the development of the small agricultural settlement. The third workshop, in 1987, focused on the revitalization of the area close to the Danube, in Budapest, around the tomb of the Turkish holy man Gül Baba. The fourth one, ‘Budapest on the Blue Danube’, held in 1990 — after the fall of communism — concentrated on the site of a world exhibition to be organized jointly by Vienna and Budapest. The final workshop, in 1992, returned to the site of Polónyi’s beginnings as a planner: Lake Balaton.

Polónyi invited Imre Makovecz, probably the sole postmodern architect from a state-socialist country with recognition in the West, and the protagonist of an ‘organic’ architecture that expressed national identity, to the first two workshop seminars. Makovecz’s open criticism of Marxism, state socialism and its system of planning contributed to his international reputation as a voice of the opposition, but this did not hinder some large commissions that came mostly from local authorities at this time. While ‘new’ representatives of the Marxist renaissance, such as Szelényi, criticized the large housing estates from the perspective of the political left, Makovecz’s criticism came from the opposite direction. No wonder that this triggered the ire of the ‘old’ Marxist architect-turned-academic Máté Major, who felt reminded of the period of the Big Debate and the arguments for introducing socialist realism. He published a series of articles criticizing postmodern architecture in general, and Imre Makovecz and his followers in particular. ‘We have the Hungarian postmodernists who intend to concoct a new architecture out of Hungarian folk and art nouveau architecture. … Postmodernism has infected the University, the design offices, and even the Union of Hungarian Architects’, he complained (Major 1981b: 28). According to Major, historicism had played a positive role in the 19th century: it had prepared the way for art nouveau architecture and, in turn, for modern architecture — because it made the absurdity of eclecticism obvious. But postmodernism, as the ‘radical eclecticism’ of the 20th century was nothing more than a ‘backward, antisocial and anti-architectural phenomenon, which, like all empty fashions, will sink in its own swamp. Reason, the source of creative thought, cannot be destroyed — not even in architecture’, wrote Major, referring to Georg Lukács’s Marxist critique, in The Destruction of Reason, of irrationality as an international phenomenon of imperialism (Major 1981b: 34). This was not without some irony, considering their earlier debate. If a postmodernist like Charles Jencks disregarded primary usefulness as the specificity of architecture, argued Major, architecture would disappear in a quagmire of semantics, metaphors and analogies: ‘Young architects in Hungary are impressed by this nonsense, since postmodernism creates the illusion of the total freedom of design’ (Major 1981b: 32). Confusing architecture with literature: in Major’s eyes Jencks had repeated Lukács’s error some thirty years later.

After the collapse of state socialism in 1989, ‘non-aligned’ intellectuals such as Polónyi were seen as potential candidates for positions in city governments. They were supported by the party Alliance of Free Democrats (Szabad Demokraták Szövetsége, SZDSZ), which included many former neo-Marxists from the ‘democratic opposition’. Ironically, it was precisely the fall of communism, the opening of the borders and the extension of the EU that lessened the intensity and significance of East-West encounters. Expo ’95, with the title ‘Bridges into the Future’, which was to be organized jointly by Vienna and Budapest, was abandoned in 1991, two years after the collapse of state-socialism: first the Viennese voted against it, then Budapest followed suit. When Polónyi organized a summer school on Lake Balaton in 1992, he and his Team 10 guests reminisced about the 1950s with nostalgia. When Polónyi, once the ‘King of the Southern Shore’, returned to his empire, he saw that it had been destroyed by new commercial development. In Alison Smithson’s elegiac words:

We have to come to the point where buildings are not always the answer to our wellbeing … so perhaps we should look again at the European Virgilian dream … which, in some way, is where Lake Balaton started in the 1950s and why Team 10 liked Pologni’s [sic] sense of a socialist leisure served by discrete, simple seeming structures standing among untouched trees in a still Virgilian landscape; service structures put down with a light touch so that the lake area of Balaton could continue a little longer its dreamy life. (Smithson 1994: 144)

Reminiscing about the time of her childhood, when the world was still a safe place, she concluded, along with a diagram (Figure 5):

Our cities — our countries even — can no longer be assumed safe. This seems to me to make it all the more important that at least some leisure places should continue to turn away from materialistic, heedlessly commercial, pressures and offer, with a fresh authenticity of form, an idea of the Virgilian Dream in the idyllic setting of Lake Balaton. (Smithson 1994: 145)

Returning to the issues raised in the introduction, it seems to me that critical theory was indeed possible in state-socialist Hungary. It clearly had effects on architectural theory, and was a major impetus in the development of two characteristic positions: the insistence on the ‘specificity’ of architecture, on the one hand, and the critique of ‘étatist’ planning, on the other. Both largely developed from a critical analysis of the given societal conditions, without ideological influences from the likes of Jameson or Tafuri. Since the ruling ideology of Marxism-Leninism blocked all serious discourse on society, truly ‘critical’ theories were developed on a neo-Marxist or a post-Marxist basis (excluding non-Marxist social critique). Therefore, the critique of a system that claimed the Marxian tradition for itself meant the rejection of a monolithic ‘critical theory’ as well as the emergence of critical theorists who took on the task of analyzing the objectivations, institutions and practices of state-socialist society.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Unpublished Sources

Polónyi, K and Konrád, G. 2000. Praying in a Cathedral Is Different from Praying at Home. An Interview with Károly Polónyi and György Konrád, Anonymous Interviewer. Manuscript fragment, undated, courtesy Anikó Polónyi.

Published Sources

Aalto, A. 1940. The Humanizing of Architecture. The Technology Review, 43(1): 14–16.

Bonta, J. 2008. A magyar építészet egy kortárs szemével 1945–1960 [Hungarian Architecture in the Eyes of a Contemporary 1945–1960]. Budapest: Terc.

Gábor. E. 1972. A CIAM magyar csoportja 1928–1938 [The Hungarian Group of the CIAM 1928–1938]. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Gábor, L and Párkányi, M. 1979. Az információ vétele és továbbítása az ipari építészetben [The Reception and Transmission of Information in Industrial Architecture]. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Heller, Á. 1984. Everyday Life. Trans. G.L. Campbell. London, Boston: Routledge & Kegan. (Hungarian ed., 1970: A mindennapi élet. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.)

Konrád, G and Szelényi, I. 1979. Intellectuals on the Road to Class Power: A Sociological Study of the Role of the Intelligentsia in Socialism. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Köpeczi, B. (ed.) 1970. A szocialista realizmus [Socialist Realism], 2 vols. Budapest: Gondolat.

Lukács, G. 1981. Die Eigenart des Ästhetischen. 2 vols. Berlin, Weimar: Aufbau-Verlag.

Lukács, G. 1985. A humanizmus és a barbárság harca [Struggle Between Humanism and Barbarity]. Trans. I. Csibra. Budapest: Lukács archívum és könyvtár.

Major, M. 1951. Zűrzavar mai építészetünkben [Confusion in our Contemporary Architecture]. In: Vita épitészetünk helyzetéről [Debate on the Situation of Our Architecture], 17–28. Budapest: Magyar Építőművészek és Iparművészek Szövetsége Építészeti Szakosztály.

Major, M. 1967. Az építészet sajátszerűsége [The Specificity of Architecture]. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Major, M. 1969. Előszó [Foreword]. Építés–Építészettudomány [Building and Architectural Science], 1(1–2): 3–4.

Major, M. 1974–1984. Geschichte der Architektur. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, Berlin: Henschelverlag Kunst und Gesellschaft. (vol. 1: 1974, Vol. 2: 1979, Vol. 3: 1984).

Major, M. 1981a. Egyetlen vitám Lukács Györggyel [My Only Debate with Georg Lukács]. Valóság [Reality], 24(3): 37–41.

Major, M. 1981b. A ‘posztmodern’ építészetről egy új magyar kiadvány ürügyén [On ‘Postmodern’ Architecture on the Pretext of a New Hungarian Publication]. Valóság [Reality], 24(5): 24–34.

Major, M. 2001. Tizenkét nehéz esztendő (1945–1956) [Twelve Hard Years (1945–1956)]. Lapis Angularis III. Források a Magyar Építészeti Múzeum gyűjteményéből. Budapest: Magyar Építészeti Múzeum.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Technical University Berlin. 1968. The Computer in the University. Joint Summer Conference July 22 to August 2, 1968. Berlin: Technische Universität.

McLuhan, M. 1962. The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Miskolczi, M. 1980. Város lesz, csakazértis… [A City Evolves, In Defiance…]. Budapest: Szépirodalmi Könyvkiadó.

Moravánszky, Á. 2015. Peripheral Vision: Charles K. Polónyi and the Humanization of Architecture. In: Moravánszky, Á. (ed.), Lehrgerüste. Theorie und Stofflichkeit der Architektur, 285–305. Zurich: gta Verlag.

Moravánszky, Á. 2017. Re-Humanizing Architecture: The Search for a Common Ground in the Postwar Years, 1950–1970. In: Moravánszky, Á and Hopfengärtner, J (eds.), Re-Humanizing Architecture: New Forms of Community, 1950–1970, 23–41. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Perényi, I. 1951. Nyugati dekadens áramlat a mai építészetben [Western Decadent Tendency in Contemporary Architecture]. In: Vita épitészetünk helyzetéről, [Debate on the Situation of Our Architecture], 7–16. Budapest: Magyar Építőművészek és Iparművészek Szövetsége Építészeti Szakosztály.

Plommer, H. 1975. Marxist History. Architectural Design 45(4): 254.

Polónyi, K. 1981. A nagy számok építészete [Architecture of the Great Numbers]. Valóság [Reality], 24(2): 58–74.

Polónyi, K. 2000. An Architect-Planner on the Peripheries. The Retrospective Diary of Charles K. Polónyi. Budapest: Műszaki Könyvkiadó.

Révai, J. 1951. Révai József összefoglalója [József Révai’s summary]. In: Vita épitészetünk helyzetéről [Debate on the Situation of Our Architecture], 57. Budapest: Magyar Építőművészek és Iparművészek Szövetsége Építészeti Szakosztály.

Smithson, A. 1994. Buildings Are Not Always the Answer … or The Old Story of the Virgilian Dream That We All Might Like to Move Towards Again. In: International Workshop ’92 for Students of Architecture: Marinas on the Lake Balaton, 144–45. Budapest: Budapesti Műszaki Egyetem.

Szelényi, I and Konrád, GY. 1969. Az új lakótelepek szociológiai problémái [Sociological Problems of the New Housing Estates]. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Tafuri, M. 1969. Per una critica dell’ideologia architettonica. Contropiano, 2(1): 31–79.

Vázsonyi, D. 2014. Neomarxista ellenzékiek társadalomfilozófiai nézetei a ‘hosszú hatvanas években’ (1963–1974) [Sociophilosophical Views of Neo-Marxist Intellectuals in the ‘long Sixties’ (1963–1974)]. Eszmélet [Consciousness], 26(103): 32–56.