Style versus Styles

This essay focuses on ‘style’ as a concept that emphasizes human action upon matter. To conceive of style as a shaping force, or as an attribute of action, harks back to the very origin of the word, to ancient rhetoric where the stylus, or, rather, the marking of the stylus upon a wax tablet, was used metonymically to describe specific modes of elocution in written and oral discourse, both the written and the spoken being dependent upon body performance. How the emergence of the modern concept of style moved away from that rhetorical or literary tradition, forging instead a tool for art’s ‘historical’ analysis, is well documented (see, for instance, Berel 1979; Sauerländer 1983; Whitney 1990; Van Eck, McAllister and Van de Vall 1995). This shift is generally envisaged as one of attention from the individual author’s performance towards the need for categorizations. Yet even the broadest style-based system of art historical classification could only be discovered through the careful study of individual works, and is thus based upon phenomenological insights. Such empathetic, almost tactile, closeness to art objects has been both the biggest weakness of stylistic analysis and also its most enduring strength. The contextually subtle and politically nuanced art history of today does not easily accommodate subjective formal analysis of artifacts, laden as it is with an idealism that privileges origin and the moment of creation. Yet the analysis of style retains the enormous advantage of a paradoxical objectivity, where artifacts, and the ways they are made, remain the primary data.

I am interested in such a corporeal presence in style theory in the modern period, what I call its ‘performative’ dimension. By performative, I simply mean style understood as an act performed, the product of bodily gestures, not unlike the stylus on the wax tablet. After all, the modern redefinition of style was part of a general effort to understand art in its becoming, in its historical evolution, and therefore as the product of active change. The famous passage in the introduction of Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums (1764) makes this explicit: ‘The history of art is intended to show the origin, progress, change, and downfall of art’ (Winckelmann 1880: 107). Obsessively attentive to the way Greek art continually transformed, and how, even at its peak, it moved from the grand to the beautiful style, Winckelmann showed how the emergence of the ideal was part of a process, and that the ideal itself had movement inscribed within it. The great significance of the Laocoön within his story lies in its presentation of a particular ‘moment’, thereby incarnating the tension between art as imitation and art as process. For Winckelmann, stylistic analysis, conceived as art history’s master key, was a method by which thought may observe its own movement from an aesthetic viewpoint. Through his passionate descriptions, Winckelmann sought to re-enact for the modern artist the mental movement of the Hellenes, and thus, ostensibly, regenerate modern art. It was of course a form of idealism, but understood as ideas in action.

By the 19th century, as biologists, geologists, ethnologists, and archaeologists were all equally absorbed by the contemplation of the enigma of time, style was ever more sharply used as a method to make historical change a palpable process. Within the best tradition of German art history — say from Franz Theodor Kugler (one of the key authors to shift ‘style’ from its literary to its historical meaning) to Heinrich Wölfflin via Jacob Burckhardt — an empathetic intimacy towards art objects is communicated to the reader, thus affording a bodily understanding of the nature of stylistic mutations. Burckhardt, for instance, sought to identify the human energies and actions that formed the impulse to the creation of the great architectural works of the Renaissance. Far from merely taxonomic categories, style, for him, was the will and vision of human actors inscribed in stone, like the stylus in wax (see Frommel 2012: 120). Later in the century, Wölfflin sought to show how architectural style, corporeal presence, man’s deportment, and his habits are tightly connected. He thought that style arose ‘first in costume, the clothes that determine the body’s range of movements’ (Payne 2012: 139).

Though not an art historian, the architect Gottfried Semper, who assimilated style with performance, was a key influence within that German tradition. Mari Hvattum has mapped well how Semper’s ‘practical aesthetic’, or his morphological approach to the issues of style and more generally art, was intertwined with an understanding of the somatic gestures proper to human crafts (weaving, above all) (2004). Style was thus originally tied to bodily pragmatics. It was inherently related to the applied arts. According to Alina Payne, the connection that Semper established between the ‘decorative arts, small objects and artifacts — in other words all those objects that come in close contact with the body — is perhaps [his] most momentous contribution … to architecture but also to the history of art’ (2012: 143). It was in such bodily apprehension of the world that Semper identified the primordial ‘instinct towards art’.

Associating it with instinct, Semper makes style a creative process rather than a formal norm. In this light, style becomes a basic concept within a theory of creativity. The German Romantics had been the first and most vocal in identifying style with instinct. ‘Art is creative long before it is beautiful’, writes Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in 1772 (Goethe 1986a: 8). An artist achieves style not when he imitates nature correctly, but when he creates authentically, following the same productive power or instinct as nature herself. ‘Style rests on the essence of things’, writes Goethe in his essay, ‘Simple Imitation, Manner, Style’, of 1789 (Goethe 1986b: 72). Following directly upon these early writings of Goethe, August Wilhelm von Schlegel, criticizing the old definition of style as the specific ‘manner’ of an individual writer, redefined the term as an artist’s capacity to transcend his individuality, to create works that achieve a status analogous to the production of nature. ‘Art’, he writes, ‘must create spontaneously, like nature, shaping works that are organized and living, to which movement is communicated … by an interior force, like the solar system’ (Schlegel 1847: 397).

I have undoubtedly moved too quickly here. But I wanted to first emphasize a broad tendency in style-theory to be attentive to the ‘communication of movement into things’. Seen from that angle, and despite Schlegel’s desire to move the concept away from the individual manner of an artist, style inevitably returns to the artist’s activity. The definition of style as a ‘shaping force’ accentuates the power of the act, and thus the particular and the innovative, as opposed to the prescriptive and the taxonomic. That context is useful to better understand Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc’s famous opening remark for the ‘Style’ heading in his Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle, published in 1866: ‘There is style, and there are the styles’. In the plural, ‘styles’ refers to a normative taxonomy differentiating various schools and epochs. But, in the singular, it refers to the creative act itself, to humanity’s productive power generally. Viollet-le-Duc thus makes explicit the ambivalence lying at the heart of the art historical concept of style: a normative tool of classification versus a creative instinct.

These two competing definitions of ‘style’ are not ‘either/or’, but rather are deeply enmeshed with one another. Style understood as a creative ‘power’ is what produces the coherence of an artistic period: ‘style’ in the singular — the creative action — generates ‘styles’ in the plural. The one is concerned with the performance, the other with the product. In his essay on manner and style quoted above, Schlegel (1847: 404) brings the two definitions together: ‘Where we observe a group of artistic productions constituting a totality, seizing a regularity in their development, we are authorized to use, for the designation of the various epochs, the denomination of style’. So ‘style’ understood as the stamp of the spirit upon materials is also at the basis of the coherence of an artistic period — ‘style’ authenticates styles. Even in common parlance, the term style in the 19th century always kept the weightier dimension of a range of works ‘naturally’ produced out of a complex set of conditions: not an artist’s ‘manner’, but a form springing from a deep-seated interiority reflecting a shared milieu and historical horizon. Yet, inevitably, a tension existed between these two dimensions, reflecting the basic struggle of the innovative and the individual with the collective and the normative.

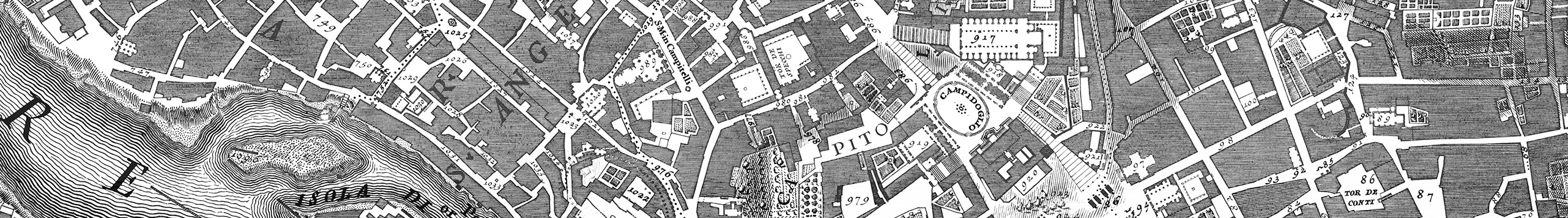

Within the large panorama of 19th-century architectural thought, the most interesting authors will emphasize style as a formative process at the expense of style as a classificatory method. Even such a dogmatic and conservative classicist as the archaeologist Antoine Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy put much more emphasis upon the ‘originating principle from which art is born’ than upon a taxonomy of the historical styles — the variety of which he had relatively little interest in. Though not an adept of the Romantic, combustive definition of the creative process as defined by Schlegel, Quatremère de Quincy did see art, and more specifically architecture, not merely as imitation (though that was part of it) but as the product of the particular conditions from which it originated. It was above all a social act, tied to certain material conditions as well the force of habit. Quatremère de Quincy still maintained idealist and thus external standards by which to judge the quality of such production, thereby curbing creative innovation. Style, for him, was subsumed under the classical concept of ‘character’, and thus still embedded in the rhetorical tradition (Baridon 2007). In contrast, theoreticians fascinated with stylistic change would adopt a more empirical attitude, turning their attention to the architect’s active struggle with material and constructive issues. In the work of the art historian Carl Friedrich von Rumohr, for instance, style takes form via the architect’s confrontation with technique and material. Rejecting Winckelmann’s idealism, Rumohr turned away from systematic classification to consider each artist’s creative process as individual and unique (see Rumohr 1827–31). The whole ‘tectonic’ tradition in German architecture is embedded in such attention to the act of making. Perhaps no image illustrates better the performative dimension of style than Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s famous canvas A Glimpse of Greece’s Golden Age of 1825, where architecture is portrayed as a constructive act in dynamic exchange with nature’s own productive power (Figure 1).

Style as a Bodily Act

Schinkel’s portrayal of communal civic consciousness as a (public) architectural performance only hints at the depth of investment in a corporeal definition of the creative act in the 19th century. Schinkel himself pursued this type of speculation more privately in his ‘Philosophical Notebooks’, where he investigated the ‘primitive style principle of architecture’ as a vital act of existence (Kupferstichkabinett Berlin S.M. H.III.S1, quoted in Wolf 1996: 19). To convey in more detail how the body was mobilized to explain artistic creation, I will instead turn to France, and more particularly neo-Catholic, and, concomitantly, neo-Gothic discourse, taking the time to consider in more detail its curious definition of a ‘physiology’ of art. Within the radical fringe of that rather large corpus, the creative act is defined entirely in corporeal terms, but mystically, reaching deep inside the body to attain the fundamental synthesis as a form of ‘incarnation’ of the spirit. That corpus, borrowing esoteric thought, may not be as well known nor as coherent and systematic as the German material I’ve just glossed through, but it was influential. It resurfaces in mainstream criticism, for instance in the work of Viollet-le-Duc, with which my essay will end.

To get a first idea of what that ‘inward turn’ entailed, we can start with a striking passage from the writings of the young writer (and medical doctor) Charles-Augustin de Sainte-Beuve, written in 1830 when the influence of the Saint-Simonians was at its peak in French literary circles, and when Sainte-Beuve had not reached celebrity status. Sharply criticizing the abstract Hegelianism of Victor Cousin and Théodore Jouffroy, Sainte-Beuve calls for a complete surrender to the ‘life’ of the body to remedy contemporary social ills:

To live of the total, deep and intimate life, not only of the distinct and clear life of our reflected consciousness and our deliberate acts, but of the multiple and converging life that springs forth from all points of our being, the life that we sometime feel through the most indisputable sensations flowing in our blood, shivering in our substance, quivering in our flesh, rising in our hair, moaning in our entrails, and welling up and whispering amongst our tissue; of the unified, indivisible life, which in its physiological reality embraces within us the most obscure movement up to the most deliberate manifestation of the will, which holds man in his entirety, gripping functions and organs within the network of a sympathetic irradiation. (Sainte-Beuve 1875: 40).

Despite such lyricism, Sainte-Beuve himself quickly moved away from such ‘physiologism’ — even if his literary biographies, which would make him famous, will always retain the ‘person’ as the key to understanding the work. But another medical doctor in the orbit of the Saint-Simonians, the radical French socialist historian, politician, and utopist Philippe Buchez, will take up the concept of ‘embodiment’ within his aesthetic theory. Though largely forgotten today, Buchez was one of the key ideological sources of the French neo-Gothic movement and amongst the earliest to theorize aesthetic response on the mode of bodily affect. With the help of his close collaborator, the physiologist Laurent Cerise, he will use physiology to describe the nature of art’s operation upon the mind and body. Buchez’s and Cerise’s psycho-physiological aesthetics should not be confused with later German empathy theory, as it remains entirely subsumed under an historical and moralistic understanding of art’s social role: art as the didactic function of inculcating moral ideas through a sympathetic, bodily mechanism. Theirs was an idealistic aesthetic rather than the pure expression of a bodily phenomenology.

That Buchez used physiology to explain art, and especially architecture, is not surprising given that his entire social science was founded upon an analogy between the workings of society and the workings of the human body. Such a Saint-Simonian model was not original in 1830, but Buchez developed it very much in his own way, and in an unusually sustained fashion, drawing directly from anatomical research. The most original exposition of his ideas remains his intricate Introduction à la science de l’histoire, ou science du développement de l’humanité, published in one volume in 1833 (completely recast and rewritten in two volumes in 1842 — I draw from the more interesting earlier version).

As one would expect in any Romantic social science, he begins with a description of the moral illness of his century, caused by the lack of a common faith and resulting in the disintegration of the social body — a break-up whose key symptom was, for him, the radical division between social classes. Humanity’s ‘condition of existence’ (an expression drawn from Cuvier’s comparative anatomy) is society, and society is healthy only if it is held together by a unifying (religious) idea, what Buchez calls ‘un but commun d’activité’. Thanks to such a common goal, individuals all rally, through a ‘sentiment sympathique’, around a common desire, a common system and a common action — sentiment, reason, and activity being, in Buchez’s social science, the three human faculties successively involved in any form of individual or social behavior. The physiological model for understanding social unity is our body’s nervous system, the analogy being no mere image for Buchez, as his ‘social physiology’ identifies an actual liaison between the individual’s body and the social world.

If from a religious (or absolute) point of view, our sense of certainty comes from our awareness of fulfilling a function, it can also be drawn, according to Buchez, from the ‘consciousness of our own organism, the obscure fact that all debates on certainty have always tried to elucidate’ (Buchez 1833: 179). By so turning inwardly, reaching, as Sainte-Beuve had called for, within the body as a basis for certainty, Buchez claims ‘to restitute (logic) to its ancient expressive power, throwing light upon the obscurity hidden under the words logos, verbum’ (Buchez 1833: 189). He delimits its ultimate form in his description of l’acte synthétique a priori, the highest creative act of the human organism carried only exceptionally, producing the flashes of insight that chart the history of humanity. Buchez’s description of that type of dazzling revelation is as striking as Sainte-Beuve’s, a sort of Romantic recasting of Descartes’ cogito:

The state of creative synthesis demands the highest degree of exaltation … It indeed calls for an enormous effort, on the part of whomever is at work, to completely isolate oneself from one’s surroundings, so as to see only within oneself, to perceive only one’s own organism in terms of its own aptitudes contained within … ; an enormous effort to isolate oneself from all form of memory, in order for one’s own personality to be activated pure in the mind’s eyes; and moreover this effort must be performed in a single moment. This state of a priori synthesis then assumes that l’homme intérieur is active in all parts of his body, so as to perceive himself entirely in an instant, to feel and summarize himself, and thus to find the word, the verb of his own existence. (Buchez 1833: 194–95).

With such synthetic action, an overwhelming, unified bodily consciousness is reached, obliterating memory and habit while disclosing a new historical truth. This self-sensing is the penetration of the spiritual into the vegetative or carnal world, such intercourse leading to the realization. It is through such a founding act that humanity periodically ‘regains its unity’ (Buchez 1833: 212–13).

Following from this theoretical construct, art is defined by Buchez (1838: 709) as ‘the totality of expressive means by which human sentiments are propagated by way of imitation or sympathy’. Art transmits to others what was originally an inward, private experience: ‘Art (…) is a sign that emerges from man and returns to him’ (Buchez 1838: 713). But, following upon Buchez’s social physiology, not any species of ideas can constitute itself as a perfect unity in art: only high religious and social ideas can ‘seize man all together, spirit and flesh, overcoming his egoistic instincts’ (Buchez 1838: 712). Experiencing the highest expression of art, in Buchez’s term, is thus the transmission of the same feelings associated with the creative a priori synthetic experience described above. Since each individual type of art in itself cannot seize at once all bodily sensibilities, only a reunion of the arts can generate the all-powerful sentiment associated with synthetic, or, in this case, synesthetic experience. The arts are indeed ‘naturally unified one to the other by the closest of ties’ (Buchez 1838: 712), losing power the more they isolate themselves. Architecture provides the unifying vessel for such synesthetic experience. Brought together in the sacred precinct, the arts touch the totality of the body’s sympathies, forming a sort of analogous body. So Buchez defines humanity’s highest ‘synthèse expressive’, when ‘man’s expressive instrumentality’ reaches beyond the individual to become a social act, as the product ‘of a single movement’, what he calls ‘l’acte artiste’ (Buchez 1838: 276). The work of art so conceived was the product of a total bodily act, a process which, in turn, insured maximum impact upon the beholder, galvanizing corporeal affinities in the highest synesthetic experience conceivable.

Buchez’s ideas form an undercurrent within the bustling aesthetic speculations of the 1830s and 1840s in France. Balzac himself will use Buchez as model for his portrait of the great writer d’Arthez in Illusions perdus (1837–43). Buchez’s physiological, or, more accurately, his ‘corporeal/transcendental’ understanding of art was also, most probably, at the source of neo-Catholic priest Félicité Robert de Lamennais’s well-known and influential lyrical description of a synesthetic night-time experience in the cathedral. True creation, claimed Lamennais, is achieved only when man forgets himself so as to be entirely absorbed by the movement of his own thought, when an idea shines from an interior heat, ceaselessly active. As with Buchez, it is described as some form of incarnation, or, rather, the ‘re’-incarnation of the spirit: ‘poetry is but man reproducing and exteriorizing himself, manifesting his true nature in his relation to things and the creator of things, it is the incarnation of the visible word of God’ (Lamennais 1840: 349). As with Buchez, Lamennais ranks architecture highest, the crucible within which the spirit can penetrate and overwhelm the body.

Neither Buchez nor Lamennais referred to the concept of ‘style’ to describe such an authentic creative act. But others would. Around 1861, for instance, Christian writer Ernest Hello redefined the concept of style along such embodied performance. Style is ‘the explosion of our person’, writes Hello (1861: 14). Harking back to the ancient rhetorical tradition, ‘style, is living speech [la parole vivante] at the service of the living idea [l’idée vivante]’ (Hello 1861: 17). Or again: ‘Style is the expression of man’s activity. As it confronts life, the self and others, all creatures are placed in a certain relation. Style is the expression of the intimate action that they exercise and that is exercised within them and upon them’ (Hello 1861: 44). The life process is a shaping force which creates forms from within and which makes use of, indeed exploits, the outward circumstances.

Style as Production

This rapid exposition of the ideas on creativity and art of a few French neo-Catholic writers leads me back to Viollet-le-Duc and his conception of style. There is no doubt that Viollet-le-Duc was subjected to neo-Catholic influences early in his career, as was the entire neo-Gothic camp. Buchez’s school held regular lectures in the house of Dr. Ulysse Trélat, a few meters away from Viollet-le-Duc’s family house on rue Chabanais in Paris, Trélat being himself a close friend of the Viollet-le-Ducs. Viollet-le-Duc undoubtedly attended these gatherings, in which art and architecture were frequent topics of discussion (see Bressani 2014: 131). This being said, nothing about Buchez’s teaching is mentioned in Viollet-le-Duc’s immense corpus of writing. It was part of an early ‘Romantic’ phase that was best kept quiet as Viollet-le-Duc sought to climb the higher rungs of the French architectural establishment. But it colors his writings, starting with his account of his own synesthetic experience inside Notre-Dame cathedral (Bressani 2014: 3). It is precisely because he absorbed and transformed Buchez’s (and probably Lamennais’s) more recondite ideas into a more mainstream definition of style and creativity that Viollet-le-Duc is of interest in our context. With whatever rationalist gloss he wishes to coat his definition of style, it remains, essentially, an organic and vital operation, expressive of the world’s productive power. His most striking definition of the operation is through the metaphor of blood: ‘For works of art, style is like blood for the human body; it develops it, nourishes it, gives it strength, health, duration; [it is] the power to give body and life to works of art’ (Viollet-le-Duc 1866: 476). The theme of incarnation is not far behind such a statement, except that any religious connotation is now expunged. For Viollet-le-Duc, style is not the expression of God, but of the will. Buildings or human creations are endowed with ‘style’ when they are the quasi-spontaneous product of a battle waged between means and end. Then only do they possess the vigor and unity brought about by an overall shaping act.

To examine the question in more detail, I will turn to Viollet-le-Duc’s well-known comparison of three metallic water vessels, presented in the sixth of his Entretiens sur l’architecture (1859), to explain the ‘constitutive elements of style’ (Viollet-le-Duc 1863: 179–84; see also Bressani 2014: 382–386) (Figure 2). By comparing the three vessels, he outlines how human artifacts acquire or lose the special quality of style. The first, produced from scratch in the most straightforward manner, is the exemplary one: starting from a flat sheet of copper, explains Viollet-le-Duc, the craftsman beats the plane surface to produce a hollow body; he leaves a flat bottom to ensure that the vessel can stand firmly on the ground; he contracts the upper orifice to hinder the liquid from spilling; he widens its edge to allow easy pouring; he rivets handles on either side to carry the object, making sure that the handles do not stick above the top of the vessel so that the latter can be inverted to be drained dry. He thus describes the process as a series of successive actions: beating the metal, contracting it, widening it, riveting it, etc.

Three water vessels. Wood engraving. From Viollet-le-Duc (1863). Private collection.

The two subsequent transformations of the vessel presented by Viollet-le-Duc spoil the purity of the first. A second coppersmith, wanting to ‘attract purchasers by the distinction of novelty’, discreetly rounds the base and handles with a few extra blows of the hammer. Then a third coppersmith comes along, who, seeing the success of the rounded vessel on the marketplace, further rounds the bowl and its handles. The vessel can no longer be turned upside down for drainage without damaging it. ‘This last workman, having lost sight of the principle, bids farewell to reason, and follows caprice alone; […] he has deprived a form of its proper style’ (Viollet-le-Duc 1863: 182).

In many aspects, Viollet-le-Duc is repeating a well-worn argument. Winckelmann, for instance, had described the degeneracy of Greek art as the advent of the style of the imitators (Stil der Nachahmer), when artists abandoned grandeur (Grossheit) in order to confer smoothness and softness on all forms, thinking that they were making them more agreeable, while they were only making them more dull and insignificant. Schlegel would also describe the decline of Greek Art as a progression towards the mellow, the rounded. Viollet-le-Duc relates to that tradition insofar as he, like Winckelmann and Schlegel, understands art as a process, not simply as an imitation. But neither Winckelmann nor Schlegel and their followers would ever describe the greatness of ancient art in utilitarian terms. Yet, for Viollet-le-Duc, it was the capacity of the first craftsman to create a useful object that conferred style to his work. How are we to understand that?

The first thing to grasp is that use-value was not, in and of itself, the source of the first vessel’s special appeal. If it had been, style would be a relative quality, simply denoting an object’s appropriateness to a specific context of use: if the use were to change — if, for instance, we were to use Viollet-le-Duc’s copper pot for something other than carrying water — the object would automatically lose its style. That is obviously not what Viollet-le-Duc had in mind. Style was inherent to the first vessel, whatever its use, even when reduced to a mere exhibition object in the Crystal Palace. What Viollet-le-Duc wanted to illustrate was not the usefulness of the object, but the fundamental nature of the creative process. The important aspect was the shaping action: the first vessel is endowed with style because it is the ‘natural’ or ‘organic’ product of a craftsman’s transformation of a piece of material towards the realization of a specific end. What is crucial is the transformation, not the use-value: the first vessel is ‘stamped’ with a special distinction through the confrontation, or the struggle, of a craftsman with a piece of metal which he needs to transform into an object for human use. It is the directness and the earnestness of that effort which triggers the ‘spontaneous combustion’ that generates style.

‘Production’, wrote Viollet-le-Duc at the onset of his discussion, ‘requires a process of mental fermentation, resulting from contrasts, from dissimilarities, from a disparity between reality and what the mind conceives’ (Viollet-le-Duc 1868: 178). The artist or the craftsman cannot make a true creation without the existence of a gap between reality and idea: it is in bridging that distance that the coppersmith has been able to imprint style onto matter — nothing of the basic process changes, be the goal utilitarian or more spiritual. A vessel so produced condenses an ensemble of disparate life circumstances — human need shaped in the form of an object. It is thus not the vessel’s usefulness that Viollet-le-Duc wishes us to contemplate; it is rather the piece of material which has been shaped for a specific end: the will’s objectification in a thing.

In his Dictionnaire raisonné, Viollet-le-Duc summarized his conception of style in the article ‘Construction’, as follows:

In works fabricated by men who depend only on their own resources and their own strength, there is always a certain sum of intelligence and energy of great value for those who are able to see [pour ceux qui savent voir], even if these works may be imperfect and rough. Such quality is absent in works produced by men who are highly civilized, but who are provided by industry with such a wealth of things that they can satisfy their needs without any effort. (Viollet-le-Duc 1858: 13).

It is the energy deployed that confers distinction to the work. British architect Owen Jones expressed a similar idea in his Grammar of Ornament (1856), claiming that ‘when art struggles, it succeeds; when revelling in its own successes, it as signally fails. … what we seek in every work of art, whether it be humble or pretentious, is the evidence of mind, — the evidence of that desire to create’ (Jones 1865: 14).

Viollet-le-Duc may like to emphasize the role of reason in the process, but the exact nature of his ‘reason’ escapes definition, which is often the case in 19th-century style-theory. His drama of creation is something more spontaneous, a product of man’s ‘active imagination’. The shaping action has to be felt. And indeed: the first vessel has a taut stretched skin that displays vigor and strength; its overall form has a geometric crispness. We are made to feel the fabrication process that brought it into being. The third vessel, in contrast, has a self-conscious appearance: elegant, soft, rounded, all nervousness being lost.

In a long private note written less than a year before the sixth Entretien was published, Viollet-le-Duc pondered the role of ‘passion’ in human affairs, emphasizing how only ‘l’homme passionné’ achieves distinction. His reflection dovetails perfectly with his definition of style, further highlighting the vitality required for human activities to achieve superiority:

Passion is in everything, passion is like the nervous system applied to all things; it confers movement, … life and sentiment. There is passion in what appears to be furthest removed from it, in a mechanical occupation, for instance, or in the most complex application of reason. (MAP Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, Correspondance et rapports, 1855–59, doc. 150, document dated 25 February 1858).

Objects endowed with style, according to Viollet-le-Duc, are performative, that is to say, they are infiltrated with the special energy deployed by man in his efforts to shape matter. Viollet-le-Duc even emphasizes the need for the human hand to be involved:

No mechanical means can surpass [the human hand]. … We should not be surprised of our difficulty … in creating objects that have the charm of ancient things. The availability of mechanical means breaks the hand of the craftsman of the habit of intelligent and personal work, and all his efforts tend to imitate the dry and cold regularity of machines. (Viollet-le-Duc 1871: 172).

To be sure, Viollet-le-Duc’s theory of creativity did not rely exclusively on the presence of the human hand, as it did for John Ruskin, for instance. The mark of energy could come from other sources. But objects endowed with style always bear the physical imprint of the human will.

Such definition involving action, desire, energy, passion brings ‘style’ back again to the old art of rhetoric, which Aristotle himself had defined as the skill to provide the proper grounds for conviction thanks, in part, to ‘the arousal of the passions.’ In rhetoric, the ‘style’ of elocution identified the emotional character of a performance — how the ‘sense’ content and the bodily feelings thus generated impress themselves upon the mind of the listeners like a stylus on a wax tablet. But at a more general level, it can be understood as the matrix ‘incarnating’ the intervention of the mind in the creative process at work in public speech. It is the project, or, more accurately, the active projection of the mind. In their efforts to understand the mystery of the formation and variations of artistic cultures throughout the world, 19th-century theoreticians of art, and particularly of architecture, sought to identify the ‘single feeling’ that, projecting from the mind, created each of them as a characteristic whole. So style, understood now as a shaping force, became the essential element through which various artistic forms could be distinguished and grasped in their depth. If, in the older rhetorical tradition as defined by Aristotle, style was merely a supplement to human speech, in the 19th century that supplement becomes ‘originary’, moving from the periphery to the center.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

All English translations are my own, unless otherwise noted.

Unpublished sources

Kupferstichkabinett Berlin. S.M. H.III.S1, Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s ‘Philosophical Notebooks’.

MAP (Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine, Paris). Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, Correspondance et rapports, 1855–59, doc. 150. Document dated 25 February 1858.

Published sources

Baridon, L. 2007. Entre ‘caractère’ et ‘style’: Daniel Ramée et l’aryanité maçonnique. In: Peltre, C and Lorents, P (eds.), La notion d’‘école’. Strasbourg: Presses Universitaires de Strasbourg.

Berel, L. (ed.) 1979. The Concept of Style. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bressani, M. 2014. Architecture and the Historical Imagination. Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc 1814–1879. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Buchez, P. 1833. Introduction à la science de l’histoire, ou science du développement de l’humanité. Paris: Paulin.

Buchez, P. 1838. Art. In: Encyclopédie du dix-neuvième siècle. Paris: Bureau de l’Encyclopédie du dix-neuvième siècle.

David, W. 1990. Style and history in art history. In: Conkey, MW and Hasdorf, CA (eds.), The Uses of Style in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

de Sainte-Beuve, CA. 1875. Premiers Lundis, 2. Paris: Michel Lévy. (First published in 1830).

Frommel, S. 2012. Der Cicerone et Die Baukunst der Renaissance in Italien: Considérations de Jacob Burckhardt sur l’architecture du Quattrocento et du Cinquecento. In: Frommel, S and Brucculeri, A (eds.), L’idée du style dans l’historiographie artistique: Variantes nationales et transmissions. Rome: Campisano Editore.

Goethe, JW. 1986a. On German Architecture. In: Gearey, J (ed.), Essays on Art and Literature. Goethe’s Collected Works, 3. Princeton: Princeton University press.

Goethe, JW. 1986b. Simple imitation, manner, style. In: Gearey, J (ed.), Essays on Art and Literature. Goethe’s Collected Works, 3. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hello, E. 1861. Le style (théorie et histoire). Paris: Victor Palmé.

Hvattum, M. 2004. Gottfried Semper and the Problem of Historicism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511497711

Jones, O. 1865. The Grammar of Ornament. London: Day and Son.

Lamennais, F. 1840. Esquisse d’une philosophie, 3. Paris: Pagnerre éditeur.

Payne, A. 2012. Architecture, objects and ornament: Heinrich Wölfflin and the problem of Stilwandlung. In: Frommel, S and Brucculeri, A (eds.), L’idée du style dans l’historiographie artistique: Variantes nationales et transmissions. Rome: Campisano Editore.

Sauerländer, W. 1983. From stylus to style: Reflections on the fate of a notion. Art History, 6(3): 253–70. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.1983.tb00815.x

Van Eck, C, McAllister, J and Van de Vall, R. (eds.) 1995. The Question of Style in Philosophy and the Arts. Cambridge: Cambridge University press, 1995.

Viollet-le-Duc, E-E. 1858. Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française, 4. Paris: Bance.

Viollet-le-Duc, E-E. 1863. Entretiens sur l’architecture, 1. Paris: Morel. (Published in installments, the ‘Sixth Entretien’ appeared in 1859).

Viollet-le-Duc, E-E. 1866. Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle, 8. Paris: Morel.

Viollet-le-Duc, E-E. 1871. Dictionnaire raisonné du mobilier français de l’époque carolingienne à la Renaissance, 2. Paris: Morel.

von Rumohr, CF. 1827–31. Italienische Forschungen. 3. Berlin: Stettin.

von Schlegel, AW. 1847. Sur le rapport des Beaux-Arts avec la nature, sur l’illusion et la vraisemblance, le style et la manière. In: von Schelling, FWJ (ed.), Écrits philosophiques. Trans by Ch Bénard. Paris: Joubert et Ladrange. Original edition: Schlegel, AW. 1808. Über das Verhältnis der schönen Kunst zur Natur; über Täuschung und Wahrscheinlichkeit; über Styl und Manier, text of a lecture given in 1802, Prometheus, 5/6: 1–28. Republished in: Schlegel, A W 1828 Kritische Schriften, 2 vols (vol 2: 310–336). Berlin: Reimer.

Winckelmann, JJ. 1880. The History of Ancient Art, 1. Boston: James R. Osgood.

Wolf, SC. 1996. The metaphysical foundations of Schinkel’s tectonics. ANY Magazine, 14: 16–21.