Demystifying Hitler’s Favorite Architect

Atli Magnus Seelow, Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, SE

Magnus Brechtken, Albert Speer. Eine deutsche Karriere, Munich: Siedler Verlag, 912 pages, 2017; ISBN: 978-3-8275-0040-3, with colour and b&w illustrations.

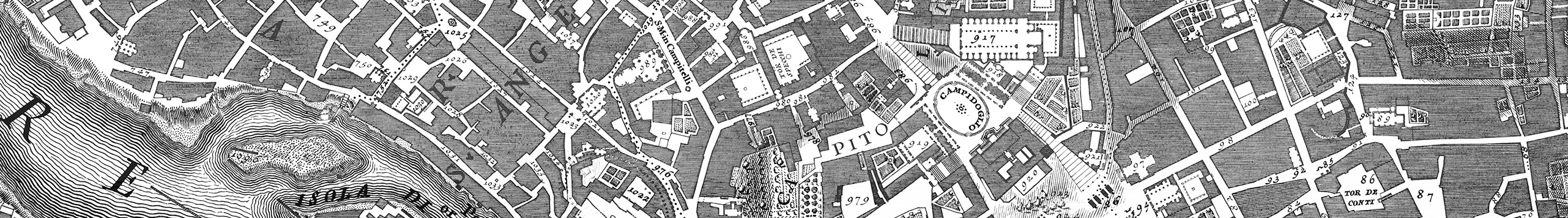

Albert Speer (1905–1981) undoubtedly occupies a special position in architectural history; his biography differs from that of all other 20th-century architects. The importance we attribute to him today is due not primarily to his work as an architect but to his role as one of the leading protagonists of the National Socialist regime, about which he spoke as a firsthand witness after World War II. At the Nuremberg Trials, Speer, despite his tireless commitment to the machinery of death and his central role in Nazi crimes, received only a 20-year prison sentence, which he served until 1966. In the Federal Republic, he became a bestselling author and one of the most cited witnesses of the Nazi era. Speer’s portrayal of the Nazi regime and Hitler’s circle shaped post-war historiography, a contribution that has been almost unchallenged. Even the authors of the two posthumous biographies of Speer, Gitta Sereny and Joachim Fest, could not detach themselves from Speer’s point of view on all issues; the biographies are based on conversations with him and (Figure 1) to a great extent ignore archival documents and historical research (Sereny 1995; Fest 1999).

The new, comprehensive, modestly illustrated bio-graphy Albert Speer. Eine deutsche Karriere, is by Magnus Brechtken, the deputy director of the Munich Institut für Zeitgeschichte and a professor at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität. Brechtken says this biography originates from his interest in the questioning of political memoirs. It is the result of many years of meticulous archival research — the endnotes and bibliography alone comprise 324 pages — unlike the earlier biographies by Sereny and Fest, which rely primarily on interviews with Speer, and the more recent one published by Martin Kitchen (2015), which is mainly based on existing literature. The critical edition of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf by Christian Hartmann and others (2016), which has been extensively commented upon, was also researched at the Institut für Zeitgeschichte.

Brechtken’s central thesis is that Speer exemplifies a ‘type of bourgeois German who consciously became a National Socialist and after 1945 neither had the will nor the insight to render an honest account of what he had done’ (Brechtken 2016: 14). Brechtken regards Speer the same way he thinks of Reinhard Heydrich (1904–1942): as role models of the ‘uncompromising generation’. This term was coined by Michael Wildt to characterize the type of leadership elite of the Third Reich embodied by the leadership corps of the Reich Security Main Office — well-educated young men who not only joined the National Socialists but also crafted a career within that group, and whose uncompromising will knew no norms or limits (Wildt 2009). Brechtken says when they melded their ‘ambition, the will to power, and personal greed’ with the National Socialist ‘Rassenkampf’ ideology, it was ‘not a coincidence, but … a calculated consideration in life’. Brechtken concludes that for Speer, ‘the will to gain power, to rule and to acquire money [was] a central pattern of his character that shaped his actions until 1945 and drove him on throughout his entire life’ (Brechtken 2016: 45).

Brechtken’s biography is divided into two long and more or less chronologically sorted halves that describe Speer’s life before and after 1945. In the first half, the author very briefly recounts Speer’s privileged youth in his affluent family home in Mannheim and later in Heidelberg. He talks about Speer’s early studies in architecture at Universität Karlsruhe, Technische Hochschule München, and Technische Hochschule Berlin, and his work, from 1927 to 1932, as an assistant to Heinrich Tessenow (1876–1950). Brechtken takes care to show that Speer very consciously — rather than almost mistakenly or unknowingly, as Speer later claims in his memoirs — joined the National Socialists in 1930 and was aware of their murderous goals. Speer purposefully and relentlessly pursued his career. He focused on gaining proximity to Hitler and, after the death of Paul Ludwig Troost (1878–1934), managed to become Hitler’s favorite architect and ‘master-builder of the movement’. Speer is responsible for the buildings of the Nazi Party Rally Grounds in Nuremberg, the New Reich Chancellery in Voßstraße, and, as the general building inspector for Berlin from 1937 on, for the monumental re-planning of the capital. After the fatal plane crash of Fritz Todt (1892–1942) in February 1942, Speer succeeded him as minister of armaments. Brechtken thoroughly refutes the perspective that Speer was ambivalent towards Hitler and National Socialism, as later was disseminated by Speer himself and others. He shows how, already as general building inspector, he acted as ‘conquest-manager’ and planner for the ‘Endsieg’, and was responsible for the eviction and deportation of tens of thousands of Jews and for forced labour in concentration camps. As minister, he ran the armaments industry, in cooperation with Heinrich Himmler (1900–45) and Fritz Sauckel (1894–1946). In doing so, Speer skilfully constructed his persona through morale-boosting slogans and alleged weaponry ‘miracles’, and at times even as a potential successor to Hitler. In the end, he commanded about 14 million workers in the armaments industry — about half of the workforce controlled by Germany, which included several million forced labourers and nearly half a million concentration camp inmates. Even when it was apparent that Germany would lose the war, Speer continued to raise industrial production very efficiently, thus extending the war — and the murders in the death camps and the death of a millionfold people at the front.

The second half of the book deals with Speer’s life after 1945: the Nuremberg Trials, the twenty years of imprisonment in Spandau, and his career in post-war Germany after his discharge in 1966. In court, Speer only selectively admitted to his crimes and, simulating atonement, assumed only an abstract overall responsibility in order to camouflage his personal responsibility. He constructed his life story anew, presented himself as a tempted artist and an apolitical technician, and positioned himself as a witness and authority on the perished Third Reich. After his release, Speer, thanks to numerous interviews and three autobiographical books — Erinnerungen (1969), Spandauer Tagebücher (1975 and 1976) and Der Sklavenstaat. Meine Auseinandersetzungen mit der SS (1981) — became a celebrated bestselling author; Erinnerungen alone has been translated into 17 languages. These memoirs, produced in collaboration with the publisher Wolf Jobst Siedler (1926–2013) and the historian and future editor of Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Joachim Fest (1926–2006), take Speer’s mythmaking to a mass-media level. Speer, the ‘good Nazi’, provides with his lies an exculpation narrative that is perpetuated many times over by countless ‘Mitläufer’ (‘hangers-on’) in post-war Germany. To exonerate themselves, they all too readily believe that he was not aware of the regime’s crimes.

With this biography Magnus Brechtken accomplishes a twofold success. First, thanks to his painstaking archival research, he effectively uncovers the last myths remaining about Albert Speer. His biography surpasses previous work by historians since the 1980s, though he acknowledges their achievements and builds on them. Matthias Schmidt (1982) and Susanne Willems (2002), for example, unearthed Speer’s leading role in the persecution and murder of European Jews; Angela Schönberger (1981) has refuted the ‘Reichskanzlei’-legend; Hans J. Reichhardt and Wolfgang Schäche (1998) uncovered the destruction of Berlin in the wake of Speer’s monumental re-planning of the city; Adam Tooze exposed Speer’s alleged armaments-miracle (2006: 554–579); and most recently, Isabell Trommer (2016) deconstructed Speer’s self-mystification and his role in the justification- and apology-discourses in post-war Germany. Also of great importance was the TV-movie Speer und Er by Heinrich Breloer, which for the first time brought Speer’s central role in the Nazi regime to the attention of a wide audience and also debunked numerous myths; the book accompanying the film reproduced numerous documents as evidence (Breloer 2005, 2006).

Brechtken also investigates the Speer memoirs and biographies. It has taken historiography a long time to unmask them as cunning apologies and to prove that they cannot be trusted. Brechtken deconstructs their influence and meticulously uncovers them, almost sentence by sentence, as manipulation or fake. He shows how Speer even instrumentalized former employees to conceal his activities and to fabricate alibis after the fact. The influence of Speer’s memoirs would not have been so disastrous if they — like the memoirs of other Nazis — had been only apologetic writings whose purpose was to obliterate traces and if they had not exerted such great power on the popular perception of the Third Reich as well as on scientific research. For example, Speer’s alleged absence from Heinrich Himmler’s Poznań speech in October 1943 as evidence of his ignorance of the Holocaust, Speer’s alleged plan of a poison gas attack on Hitler in February 1945, and his alleged refusal of Hitler’s ‘Nero’ order in March 1945 have all been picked up as historical facts and repeated many times — all of which, however, have been debunked by Brechtken as dubious stories or fairy tales, floated by Speer after the war. Brechtken mainly blames Wolf Jobst Siedler and in particular Joachim Fest for this ominous influence. How long Fest adheres to the lies fabricated by Speer can be seen from the fact that even in 2005, Fest — in total ‘ignorance and remoteness from knowledge’ (Brechtken 2017: 555) — maintains that ‘only a few further works [on Speer] have appeared since the early 1970s’ and that the ‘level of knowledge’ essentially hasn’t changed much since then (Fest 2005: 11).

One drawback of this biography is the brevity with which Brechtken investigates Speer’s work as an architect. It is reduced to a secondary discourse, in the shadow of the rest of his biography. While a number of studies have explored Speer’s architecture as a product of the regime (for an overview see Reichhardt and Schäche (2008: 9–22) and Tesch (2016: 2–8)), investigating it on its own terms represents a historiographic dilemma: either separating it from its historical context or pursuing ‘Täterforschung’ (perpetrator research), which has been rather uncommon in art history. As Winfried Nerdinger and Raphael Rosenberg point out in the preface of the first volume of their series Hitlers Architekten: Historisch-kritische Monografien zur Regimearchitektur im Nationalsozialismus, Paul Ludwig Troost (1878–1934) by Timo Nüßlein (2012), ‘Täterforschung’ has become an indispensable tool for historic analysis in ‘Zeitgeschichte’ (Longerich 2007), but for good reason it is little known in the realm of art history:

Monographs on bad artists are not written, books about the life and work of criminals are shunned in the art world. That is why for a long time there have been no historic-critical monographs on the most successful architects, painters and sculptors under the Nazi regime. (Nerdinger and Rosenberg 2012: v)

The publication of Speer’s architectural work, which he initiated in 1978 and which became known to an international audience through Léon Krier’s 1985 edition, is based mutatis mutandis on myths similar to those in Speer’s memoirs (Speer 1978 and Krier 1985). The attempt to consider Speer’s architecture as a continuation of classicism and completely detached from its political implications is based, as critics have pointed out, on deliberate euphemistic retouches and crude historic simplifications (for an overview of the criticism, see Reichhardt and Schäche (2008: 19–20)). The art historical classification undertaken in the same volume by the art historian Lars Olof Larsson (incidentally the son-in-law of Speer’s collaborator Hans Stephan) and the comparison with the Nordic classicism of the time were both systematically refuted by Winfried Nerdinger (1986). Tracing the origin of Speer’s architecture back to Schinkel and other classicists proves on close examination to be another fable that was invented by Speer in collaboration with Siedler and Fest in the memoirs.

In addition to the studies already mentioned, Sebastian Tesch recently investigated Speer’s architectural work and published the monograph Albert Speer (1905–1981) (2016) as part of the Hitlers Architekten project, which documents the architects of Hitler’s regime. This extensive examination, for the first time, of archival source material yields a differentiated picture. Architecturally, Speer first adopts the simple ‘Heimatstil’ of his teacher Heinrich Tessenow; after 1933 he orients himself to the reductionism of his predecessor Paul Ludwig Troost; then, around 1936, emancipates himself from this with an austere eclecticism; and finally, after 1938, proceeds to a richly decorated monumentalism. Speer’s architecture can only be categorized as eclectic, since he mixes the design principles and the formal vocabulary of different epochs without any discernible system. Tesch concludes that Speer’s work is from the beginning closely linked with politics and a product of the specific structure of the Nazi dictatorship. Speer’s importance to Hitler was based on the fact that the latter found in Speer a loyal and administratively gifted architect to implement his wishes. Tesch goes so far as to state that ‘the plans made between 1933 and 1945 more clearly [reflect] Hitler’s ideas than Speer’s’ (Tesch 2016: 225–227). In this sense, Speer is rightly remembered not so much for his work as an architect as for his close connection to Hitler and his role as minister of armaments, as well as for his obfuscating exculpation strategy as a war criminal after 1945. From a contemporary point of view, Speer’s disastrous moral transgression should be a thought-provoking warning to architects who offer their services to dictators.

Magnus Brechtken has produced a superbly researched and brilliantly written biography. Thanks to intensive use of archival material, he not only succeeds in unmasking the remaining myths about Albert Speer, but also in deconstructing the disastrous influence of the Speer memoirs and biographies. One can only hope that more architectural historians will follow Brechtken’s methodological example and pursue a similarly critical approach. He sets standards not only for critically investigating an architect’s life and work from a contemporary ‘Täterforschung’ perspective; his biography also is an important lesson in critically revising architectural history, especially oral history, by scrutinizing memoirs and self-portrayals.

Empathy and the Creation of Virtual Space

Angela Andersen, Centre for Studies in Religion and Society, University of Victoria, CA

ΣΕΠΤΕΜΒΡΙΑΝA/September 55, Keller Gallery, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, MA, USA, November 5–12, 2016; !f Istanbul Independent Film Festival, Istanbul, Turkey, February 16–26, 2017.

September 55 is a virtual reality (VR) exhibition that recreates the attack, during the night of September 6 and the early morning hours of September 7, 1955, on Greek, Armenian, and Jewish homes and businesses in a violent pogrom in the Pera district of Istanbul. It was later revealed that top government officials orchestrated these attacks, with the intent to drive minority communities from the country. The exhibition harnesses the experiential nature of virtual architectural environments and recreates the urban setting based on archival photographs and historical accounts. This review explores the exhibition’s recreations of historic settings and its presentation of space as well as the ways in which the experiential nature of virtual architecture has been used to generate empathy for marginalized and persecuted peoples.

Several scholars have studied the potential of virtual exhibits for delivering programmed, three-dimensional ‘cultural content,’ and the role of artists-as-coders since the 1990s (Economou 2007; Merritt 2001; Ronchi 2009). Architectural and gaming design embraced newly released VR technologies early on, but museum and gallery exhibitions have only recently accepted the potential of VR as a critical artistic medium, in addition to its recognized technical role as a teaching and presentation tool, by using it to explore new ways of helping audiences to experience and relate to social and cultural themes. The British Museum, for example, employed VR in Mummy: The Inside Story (2004 and 2011) to provide access to the layered wrappings of a 3,000-year-old Egyptian mummy, and in 2015 launched the Virtual Reality Weekend featuring a VR bronze age roundhouse. Unlike September 55, these were didactic examinations of sites and objects that did not seek an emotional response to the featured artefacts. The great affective power of immersive VR and gaming applications (McLay et. al. 2014) has been used in projects such as Digital Oral Histories for Reconciliation (2017), which explored the history of abusive, racialized education in Canada by juxtaposing a virtual school with actual recorded interviews with former students. In a similar way, September 55 is a curated visit to a fraught neighbourhood and opens space for viewers to empathize for a few moments with the seen and unseen victims of that night in 1955.

In September 55 spaces viewed through VR goggles shift during an eight-minute long series of visual and aural scapes set within a very specific temporal and spatial context (Figure 2). The display is part installation and part historical simulation, documenting the destruction in the Pera district, commonly known as Beyoğlu since the departure of its Greek residents following the attacks. As the VR activates, the transition from the empty gallery to the rooms and streetscapes of a virtual, mid-1950s Istanbul results in an evocative yet dissonant sensory experience on the cusp of the real (Figure 3).

In 1955, close to 100,000 people who identified as Greek through heritage, language, and religion were living as citizens of the Turkish Republic. Mounting tensions over the contested island of Cyprus, a minority tax, and nationalist demonstrations reached a critical point on September 6, 1955, when a bomb was planted within the Turkish consular compound in Thessaloniki, Greece. A subsequent Turkish court martial trial, convened following the military coup of 1960, demonstrated that the bomb attack had been planned by high-ranking members of the Turkish government to allow them to target Istanbul’s Greeks; their Armenian, Assyrian and Jewish neighbours were also subjected to violence. Furthermore, evidence showed that Turkish officials had distributed manipulated photographs to Istanbul newspapers with the intent to exaggerate the damages to the consulate in order to generate anti-Greek sentiment. As an outcome of the trial, Democratic prime minister Adnan Menderes and foreign minister Fatin Rüştü Zorlu were convicted and executed for coordinating the consular bombing and organizing the attacks in Istanbul’s Pera district. But by the time of the ruling, most Greek families had already departed from Turkey (Vryonis 2005).

September 55 was developed through the collaborative efforts of Çağrı Hakan Zaman, Nil Tuzcu, and Deniz Tortum, Turkish-born researchers and designers who were trained in the United States in the fields of design computation, urban studies and planning, and comparative media. They utilized a digital platform intended to be experienced through single-viewer goggles within an empty gallery interior, in combination with sound recordings transmitted through headphones. The creators researched media accounts and oral histories covering the events of 1955, but the show took much of its inspiration from four photographic archives that connect highly personal images with the larger story of persecution: the Fahri Çoker Archive of the pogrom’s ruins; the Dimitrios Kalumenos Archive of the Greek Patriarchate’s official photographs of the aftermath of that night; the archive of Armenian studio portrait photographer Maryam Şahinyan, who emigrated to Istanbul as a child when her family escaped anti-Armenian violence in central Turkey decades earlier; and images from Osep Minasoğlu’s Studio Osep, which closed when Osep escaped Istanbul to work in Paris following the pogrom. These Greek and Armenian photographers were personally and professionally devastated by the events of that night, and it is their surroundings that we see reconstructed in September 55.

The VR exhibition design establishes a visual meta-chronicle of frozen scenes from the night of the attacks, staged around a simulation of a portrait studio, a small photography shop, and a street corner. Photographic prints are mounted on the gallery walls for viewing prior to the VR experience, and also inserted into virtual frames on the simulated studio walls. All these archival images have long been available in print and online and used for exhibitions, so the significance of September 55 rests in its spatially grounded interpretation and architectural representation. The creators have broken down the physical and temporal barriers of a typical exhibition with virtual, cognitive spatial experiences, thereby breaching the emotional distance of the spectator.

The immersive medium of the exhibition harnesses the capacity of space to address political and ethical issues. The viewer is confronted with everyday scenes of work in the photography studio alternating with fearful episodes on the street. The evocation of both economic ruin and the loss of home, safety, and property also alludes to the current vulnerable situation of minorities living in Turkey. This resonates with the decades-long urban relocation of Kurds from conflict zones in Turkey’s eastern provinces, and the recent situation of over two million Syrian refugees living in Turkey who, seeking safety from a crippling war, have begun to test the patience of the administration and the populace.

Through a spatial immersion in the Pera district, the installation discourages passive spectatorship. I strained my eyes to read the headlines on a newspaper, and looked at personal objects in the room. I turned around to see who was smashing the windows of a burning apartment building, and made my way to a door that seemed as if it might provide an escape route from a horde intent on destruction. As goggles began to transmit the visuals of an Istanbul street corner, backlit figures appeared, leaning from apartment windows while flames crackled and glass shattered below. The scene changed, and within the intimacy of a mid-20th-century photography studio, relatives and family groups gathered before the camera. Their gentle words to each other formed a soundscape recorded by Turkish speakers, expressing a myriad of diminutives and affectionate terms. Familial interactions, the adjustment of a scarf or collar, the settling of a baby, and the arrangement of the room itself are reminders of what was destroyed, who was displaced, and what was irretrievably lost from the fabric of Turkish society after the attacks.

Zaman, Tuzcu, and Tortum’s design is a compelling, virtual recreation of buildings and interiors belonging to Istanbul’s once lively Greek and Armenian photography community. These urban settings and the lives of their occupants were destroyed in a single night by government-coordinated thugs. Vulnerable people throughout history have faced attacks, vandalism, and the confiscation and occupation of their architecture — their homes, businesses, and places of worship. One would wish that their route to safety was as simple as removing a set of goggles.

Criticizing the Museum

Christophe Van Gerrewey, EPFL Lausanne, CH

Stedelijk Base, exhibition design by AMO/Rem Koolhaas & Federico Martelli, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Amsterdam, since December 16, 2017.

The new exhibition of the collection of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, open since 16 December 2017, is fascinating and questionable at the same time. The two large rooms in the basement of the museum’s extension, built in 2012 by Benthem Crouwel, are for the first time used to show the permanent collection, and not to house temporary exhibitions. This was a decision director Beatrix Ruf made following her appointment in 2014. It is part of a vision for the entire building, based on a division in three parts: Stedelijk Base shows the collection; Stedelijk Turns (in the old building dating to the end of the 19th century) houses thematic presentations; and Stedelijk Now is there for temporary exhibitions.

On October 17, 2017, three months before the opening of the collection display, Ruf stepped down after allegations of conflicts of interest. Authorship(s) of this exhibition is thus difficult to discern, but the decision to show designs, drawings, photography, painting, sculpture, video, and installation all together was certainly hers. In the middle of September, in the Stedelijk’s web-text announcing the new display (‘Stedelijk Base Opens’, 2017), Ruf explained, ‘I see the collection as a whole … Each work was created at a particular point in time. By placing different disciplines side by side, we learn more about a period and are able to see new cross-connections’. Nevertheless, art dominates, evidently because the exhibition is structured according to well-known art historical movements, such as Cobra, Abstract Expressionism, and Pop Art.

Stedelijk Base is, at first sight, indeed rather generic; instead of exhibiting the collection’s individuality, it presents an unsurprising overview of 20th-century art, supplemented with furniture, design, and utensils. This curatorial choice is justifiable because Stedelijk Turns and Stedelijk Now complement each other and thus create the potential to ‘dig deeper’ (a main category at the Stedelijk’s website, next to ‘visit’ and ‘what’s on’). The exhibition design by Rem Koolhaas and Federico Martelli from AMO (the research unit of OMA) is, however, anything but basic or unsurprising. One could state that without the architects’ contribution, Stedelijk Base would have been in no way as adventurous as it looks now. This is true, at least, for the underground room. The smaller rooms upstairs, with art from 1980 onwards, have been arranged without Koolhaas and Martelli’s intervention. They appear as an uninspired encore, structured according to a rather random set of themes such as ‘AIDS’ or ‘violence’.

Ruf chose to work with AMO to develop a new kind of museological display, which she deemed necessary to respond to the challenges of an ever-growing digital culture. In the press announcement from September, she said:

The widespread use of the Internet has given us a new way to gather information: we browse, see masses of images in one go, connect them and make combinations. All of this is expressed in Stedelijk Base: in a fantastic concept designed by AMO, you can move freely through the space, see amazing combinations, and make your own connections.

In the underground space of the extension, Koolhaas and Martelli decided to place steel plates — lasered, grey or coated in white, and with a total cost of 1.5 million euros — as folding screens that do not reach the ceiling. Starting from the entrance, a chronological display runs counterclockwise from the entrance to the exit. The obliquely placed walls create zones instead of rooms, never separated but continuously ‘leaking’; no matter where you are or where you look, there is always something else to see, close by or farther away.

‘You can focus on many images at the same time’, Koolhaas explained (Smallenburg 2017). Simultaneity is indeed the starting point for group or collection exhibitions, but the question is whether what you see becomes meaningful. Is the presence of many images and artworks just a matter of providing information (as Ruf described it), or does their proximity bring about new insights? Curating an exhibition means grouping and ordering artworks in such a way that they ‘cure’ each other from the artificial museum constellation to which they belong, taken away from their original context (such as a studio or a private collection). In Koolhaas and Martelli’s design, such groupings are never architectonically reinforced but rather denounced: instead of drawing attention to ensembles or individual works, the scenography continuously points to paths that invite you to explore more — other objects, periods, genres or artistic choices are anxiously waiting to be looked at, and — in the end — every scenographic construction is precisely that: a construction, an invention by historians or curators.

The consequences of this scenographic approach are far-reaching. The chronological backbone of the exhibition (against the outer walls) is affected or breached by the architectural setting of the steel plates. The Grand Narrative of Art History is attacked by means of the crisscrossed screens, but in the space that opens up, no small, engaging, or divergent stories are being told (Figure 4). This also has to do with the deliberate lack of acknowledgement that individual works or objects might have an aura. There is not enough room, around or in between, to look at them from a distance, and — in particular — to contemplate them without immediately having to see something else (Figure 5).

With Stedelijk Base, Koolhaas and Martelli seem to renounce the traditional task of architecture to ‘house’ artworks and to assign them, as Paul Valéry stated as early as 1923, ‘their place, their task and their constraints’ (Valéry 1960). At the same time, the architects present this experiment as a new beginning and a necessary innovation of the museum in the 21st century. Koolhaas has often declared himself to have been ‘aesthetically formed’ as a teenager in the 1950s by the exhibitions of the former director of the Stedelijk Museum, Willem Sandberg (Graafland and De Haan 1996: 224). The question is what kind of aesthetical formation can a museum offer, if it models itself upon contemporary phenomena such as Instagram or Google Image Search. What is the effect of playfully criticizing art history, art historical conventions and canons, in a world where all these things seem more absent than ever? In Stedelijk Base Koolhaas is targeting a ‘new kind of museum visitor’ (Smallenburg 2017), but the result turns out to be a new kind of museum space as well — a museum defined by simultaneity, superficiality, individual impressions, objects without aura, irreducible complexity, the futility of interpretation, and the absence of authority. Traditionally, museums were bastions where these phenomena were kept out, but Koolhaas explains his interventions in such a way — and this is not the first time in his career — that criticizing his design all too easily leads to conservatism. And yet it remains to be seen whether Stedelijk Base indeed is a future-oriented mutation of museum’s exhibition space or if it will turn out to be a temporary fad.

On Shrinkage as a Current Condition

Carmen Popescu, Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Bretagne, Rennes, FR

Shrinking Cities in Romania, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Bucharest, April 20–October 9, 2016.

In April 2016 the exhibition Shrinking Cities in Romania opened in the National Museum of Contemporary Art (MNAC) in Bucharest. Two months later, the hosting institution initiated a debate on its potential displacement from its current location in Ceaușescu’s gigantic House of the People, now known as the Parliament Palace. This review will examine the exhibition on shrinkage and the debate on the institution’s displacement as two symptomatic instances of the same phenomenon: Romania’s struggle with the tensions of post-modernization against the background of political, economic, and, not least, cultural mutations as they have taken shape in the decades following the 1989 turnover.

In the past few years, the theme of shrinking cities has been a hot topic in the fields of politics, economics, geography, architecture, and urban planning, giving rise to initiatives such as the Shrinking Cities International Research Network. The manifestation of this phenomenon in Romania, however, remains largely unexamined. Major publications on shrinkage (Oswalt 2005; Oswalt and Rieniets 2006; Pallagst, Wiechmann, and Martinez-Fernandez 2014; Bontje and Musterd 2014) hardly include any Romanian case studies. The exhibition Shrinking Cities in Romania therefore not only introduced the topic to a large Romanian audience, but it also filled a gap, the size of the region of Romania, in the current research on shrinkage.

Shrinkage in Romania may be considered a play in three acts: the first act consisted of the modernization process that took place during the Romanian Kingdom (1881–1947); the second act continued this modernization through the oversized scale of industrialization during the communist regime; and the final and third act, which is still in progress, involves massive mutations brought about by geopolitical changes in the post-1989 era. The curator, Ilinca Păun Constantinescu, chose to focus only on this third phase of post-industrialization. Old industrial towns, new socialist cities, and major urban centres all diminished progressively after 1989. Half of the Romanian cities lost a fifth of their population, which affected not only their physical entity but also their social and cultural identity.

Several factors accelerated this process of shrinkage: a massive deindustrialization that is still ongoing triggered unemployment and poverty, engendering identity issues within diverse communities; a decreasing birth rate; and last, but not least, recent geopolitical mutations. After 1989, economic and other forms of migration emerged, which intensified when Romania became a member of the EU. After decades of industrialization, the constant flux towards the urban areas was reversed. The resulting dynamics of shrinkage, sprawl, and illegal urban developments in periurban areas repolarized the territory and strengthened social injustice.

This process is reflected in the three sections of the exhibition, each developed by a different team under the curatorship of Păun Constantinescu. These sections are also presented in the unconventional publication with short essays on Romanian shrinkage, printed on loose sheets of paper, forming a sort of DIY catalogue, which will be republished in the form of an edited volume, with a preface by Philipp Oswalt.

The first section was set up as an ‘information filter’. Three maps providing concrete data on shrinkage captured the size of the phenomenon both in Romania and in the entire world. A large map of Romania indicated the demographic evolution of the cities between 1989 — the year the communist regime in Romania was overthrown — and 2012, supported by statistical tables offering detailed information on a century of urban dynamics (1912–2012). A second map of the country was imagined as an interactive tool, inviting visitors to pin a red flag if they thought that their city had not decreased, or a black one if they thought it had (Figure 6). The third map situated Romania and its major cities within the global framework of shrinkage as it evolved in the second half of the 20th century. A wide display of international publications showed the range of in-depth analyses of shrinkage in various countries.

The two other sections of the exhibition revealed the complex interplay of economic, demographic, social, and cultural causes of shrinkage through various installations.

The second and largest section, ‘Urban Conditions — A Direct Investigation’, consisted of six installations. Among these, ‘Post-Industrial Stories’ (by Ioana Cîrlig and Marin Raicu) and ‘Waiting for August’ (by Teodora Ana Mihai) dealt with the population of shrinking communities, including the sensible subject of children left behind in the country by their parents who went to work in the EU (Figure 7). The third section, ‘Reactions. Interventions’ focused, by means of an art installation (by Ion Barbu and Andrei Dăscălescu), on the mining town of Petrila, a mining agglomeration being among the most symptomatic case of shrinkage.

Shrinking Cities in Romania was perceived as an important event, not just because of its size, but especially because of the great number of connected manifestations such as workshops, lectures, theatre plays, and film projections. Trying to grasp its subject by as many means as possible, Shrinking Cities appropriated tools from urban sociology, anthropology, contemporary art, and social and political sciences. At the same time, this methodological diversity resulted in a certain fragmentation and dilution of its discourse. Some installations or artistic interventions, for instance, did not aim at contributing to scholarly knowledge but at arousing debate by performing a militant act. The impact of the exhibition on its visitors was prompt: in the midst of the political campaign for the local administrative elections in June 2016, an online newspaper demanded that the theme of the exhibition be addressed by the candidates in their campaign (Costea 2016).

One essay in the DIY catalogue, ‘From the Difficult-to-Access Backside of the Parliament Palace’, was the unintentional inspiration for a debate about yet another political issue (Zahariade 2016). Alluding to the remoteness of the MNAC, the venue of the exhibition, the text touched upon a long-time controversy: why should the main museum of contemporary art in Romania be enclosed in a piece of totalitarian architecture? The author of the text did not realize that the bizarreness of the situation was actually itself the result of an act of (political) shrinkage — hence, ironically, the venue of the exhibition could be seen as yet another way of considering shrinkage in postsocialist Romania.

The controversy of the location had been an issue since the museum opened its doors in 2004 in a section of the Parliament’s Palace, which had undergone an architectural readjustment by Adrian Spirescu. One of the museum’s inaugural exhibitions in 2004, curated by Ruxandra Balaci, called Romanian Artists (and Not Only) Love Ceaușescu’s Palace?!, addressed the polemic about the location of the new museum, which had already begun to spread rapidly beyond the Romanian borders, gathering more cons than pros. The negative side of the argument was that the MNAC’s location gave rise to political incongruity, was an ethical faux-pas, and made it a decentred and isolated venue. One fifth of old Bucharest was demolished to make place for the House of the People, and therefore the association of the MNAC with this symbol of the communist regime, itself responsible for so much human and urban grief, seemed not only incompatible with the museum’s cultural mission but morally problematic. Arguments for the new location, on the other hand, were pragmatic: the domain on which the House of the People is located was largely empty, so why not take advantage of it? Some added the thrill of playing with political symbols: did the avant-garde not always defy those in power?

The founding director, who had accepted the offer of the prime minister to install the museum in the Parliament’s house, implicitly defended his choice at the opening of the museum, stressing the necessity to adopt different criteria for exhibiting contemporary art, after the examples set by Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, the Ludwig Museum, and the Tate Modern (Oroveanu 2004: 19–21). The artistic director similarly pointed to the East European tendency, after 1989, to demystify the Communist symbols by means of derision and parody. This statement implicitly aligned the awkward imprisonment of the new museum within the House of the People with the same tendency: ‘The MNAC has to be perceived as … a space for the exercise of freedom and normality, in the most abnormal place of Europe. Anti-political correctness in a building dedicated mainly to political power’ (Balaci 2004: 32–40).

Few years after the inauguration of the MNAC, a new predicament complicated the situation: it was decided that the Cathedral of the Nation — commissioned after 1989 as both a redemptive and expiatory act after the communist period — was to be built in the backyard of the House of the People, or in other words in front of the MNAC. The museum was henceforth caught between the symbols of political and religious power in Romania, unintentionally forming a triad.

Twelve years later, this attitude of derision seems to have lost part of its efficiency, especially after experiencing all the hassle of daily transportation to and from a place disconnected from the city and with the Cathedral of the Nation standing next to the MNAC. Thus, in 2016, the new direction of the museum launched a debate ‘Where to move MNAC in Bucharest?’ The e-flyer announcing the debate argued that ‘the problem in 2016 is not that MNAC is located in the House of the People, but that it cannot function as a 21st century institution within the Parliament Palace’. Numerous architects, art critics and artists participated in the debate. Unexpectedly, many of these did not favour the displacement of the MNAC. Instead, they addressed issues of urban and cultural politics, while wondering if Romanian contemporary art still had the competence and the commitment to critique mechanisms of power?

The debate about relocating the MNAC was in many ways ‘collateral damage’ of the problem of shrinkage. On the one hand, the very location of the museum is the result of the political and institutional shrinkage engendered by the change of the regime. On the other hand, a new location would be a manner of feeding Bucharest’s sprawl, even if the new venue were a building affected by shrinkage such as a former industrial site. Not to mention that building a new venue would be a rather conventional ‘modernist’ response to a present day situation that favours alternative solutions. Shrinkage is a direct consequence of modernity — a term that was strangely absent from the discourse on the exhibition or the language used during MNAC debate. By stepping into post-modernity — for post-socialist countries this entails also stepping out of the communist regime into late capitalism — shrinkage is a condition that can be turned into a starting ground, if not into a stimulus.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

Demystifying Hitler’s Favorite Architect

Brechtken, M. 2017. Albert Speer. Eine deutsche Karriere. München: Siedler.

Breloer, H. 2005. Speer und Er. Hitlers Architekt und Rüstungsminister. Berlin: Propyläen.

Breloer, H. 2006. Die Akte Speer. Spuren eines Kriegsverbrechers. Berlin: Propyläen.

Fest, J. 1999. Speer. Eine Biographie. Berlin: Alexander Fest; English 2001 Speer. The Final Verdict. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Fest, JC. 2005. Die unbeantwortbaren Fragen. Gespräche mit Albert Speer. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt.

Hartmann, C, Vordermayer, T, Plöckinger, O and Töppel, R. 2016. Hitler. Mein Kampf: Eine kritische Edition. München: Institut für Zeitgeschichte.

Kitchen, M. 2015. Speer. Hitler’s Architect. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Krier, L. 1985. Albert Speer. Architecture 1932–1942. Bruxelles: Archives d’Architecture Moderne.

Longerich, P. 2007. ‘Tendenzen und Perspektiven der Täterforschung 2007.’ Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 2007/ 14–15: 3–7.

Nerdinger, W. 1986. Baustile im Nationalsozialismus. Zwischen Klassizismus und Regionalismus. In: Ades, D, Benton, T, Elliott, D and Whyte, IB (eds.), Kunst und Macht im Europa der Diktatoren 1930 bis 1945, 23: 322–325. Kunstausstellung des Europarates, Hayward Gallery. London: Oktagon.

Nerdinger, W and Rosenberg, R. 2012. Einführung der Herausgeber. In: Nüßlein, T (ed.), Paul Ludwig Troost (1878–1934). Nerdinger, W and Rosenberg, R (eds.), Hitlers Architekten, Historisch-kritische Monografien zur Regimearchitektur im Nationalsozialismus, 1: v–viii. Wien, Köln, and Weimar: Böhlau.

Reichhardt, HJ and Schäche, W. 1998. Von Berlin nach Germania. Über die Zerstörungen der ‘Reichshauptstadt’ durch Albert Speers Neugestaltungen. Berlin: Transit.

Schmidt, C. 1982. Albert Speer. Das Ende eines Mythos — Speers wahre Rolle im Dritten Reich. München: Scherz.

Schönberger, A. 1981. Die Neue Reichskanzlei von Albert Speer. Zum Zusammenhang von nationalsozialistischer Ideologie und Architektur. Dissertation Freie Universität Berlin 1978. Berlin: Gebrüder Mann.

Sereny, G. 1995. Albert Speer. His Battle with Truth. London: Macmillan.

Speer, A. 1969. Erinnerungen [Reminiscences]. Berlin and Frankfurt am Main: Propyläen and Ullstein.

Speer, A. 1970. Inside the Third Reich. Trans. by Richard and C. Winston. (Translation of Erinnerungen.) New York and Toronto: Macmillan.

Speer, A. 1975. Spandauer Tagebücher. Berlin and Frankfurt am Main: Propyläen and Ullstein.

Speer, A. 1976. Spandau. The Secret Diaries. Trans. by Richard and C. Winston. (Translation of Spandauer Tagebücher.) New York and Toronto: Macmillan.

Speer, A. 1978. Architektur. Arbeiten 1933–1942. Frankfurt am Main, Berlin and Wien: Propyläen.

Speer, A. 1981. Der Sklavenstaat. Meine Auseinandersetzungen mit der SS [‘The Slave State: My Battles with the SS’]. Berlin: Ullstein

Speer, A. 1981. Infiltration. How Heinrich Himmler Schemed to Build an SS Industrial Empire. (Translation of Der Sklavenstaat.) New York: Macmillan.

Tesch, S. 2016. Albert Speer (1905–1981). Hitlers Architekten, Historisch-kritische Monografien zur Regimearchitektur im Nationalsozialismus 2. Nerdinger, W and Rosenberg, R (eds.). Wien, Köln, and Weimar: Böhlau.

Tooze, A. 2006. The Wages of Destruction. The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy. London: Allen Lane.

Trommer, I. 2016. Rechtfertigung und Entlastung. Albert Speer in der Bundesrepublik. Wissenschaftliche Reihe des Fritz Bauer Instituts, 27. Frankfurt am Main: Campus.

Wildt, M. 2009. An Uncomprimising Generation. The Nazi Leadership of the Reich Security Main Office. Translated by T. Lampert. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Willems, S. 2002. Der entsiedelte Jude. Albert Speers Wohnungsmarktpolitik für den Berliner Hauptstadtbau. Publikationen der Gedenk- und Bildungsstätte Haus der Wannseekonferenz 10. Berlin: Hentrich.

Empathy and The Creation of Virtual Space

Economou, M. 2007. A World of Interactive Exhibits. In: Paul, FM and Katherine, BJ (eds.), Museum Informatics: People, Information, and Technology in Museums, 137–56. New York: Taylor and Francis.

McLay, R, et al. 2014. Effect of Virtual Reality PTSD Treatment on Mood and Neurocognitive Outcomes. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(7): 439–46. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0383.

Merritt, RK. 2001. From Memory Arts to the New Code Paradigm: The Artist as Engineer of Virtual Information Space and Virtual Experience. Leonardo, 34(5): 403–8. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1162/002409401753521511

Ronchi, AM. 2009. eCulture: Cultural Content in the Digital Age. Berlin: Springer Verlag. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-75276-9

Vryonis, S. 2005. The Mechanism of Catastrophe: The Turkish Pogrom of September 6–7, 1955, and the Destruction of the Greek Community of Istanbul. New York: Greekworks.com.

Criticising the museum

Graafland, A and De Haan, J. (eds.) 1996. The Critical Landscape. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers.

Smallenburg, S. 2017. Je kunt focussen op meerdere beelden tegelijk. NRC Nieuews, December 13, 2017. Available at: https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2017/12/13/je-kunt-focussen-op-meerdere-beelden-tegelijk-a1584775 [accessed 16 March 2018].

Stedelijk Base Opens. 16 December 2017. Stedelijk, News, September 13, 2017. Available at: https://www.stedelijk.nl/en/news/stedelijk-base-the-new-collection-presentation-of-the-stedelijk-museum-amsterdam-will-open-on-16-december-2017-2 [accessed 16 March 2018].

Valéry, P. 1960. Oeuvres, 2. Paris: Gallimard.

On Shrinkage as a Current Condition

Balaci, R. 2004. Ideas (Cut&paste) During the Work in Progress at MNAC. In: Balaci, R and Velisar, R (eds.), MNAC 2004, 27–43. Bucharest: MNAC.

Bontje, M and Musterd, S. (eds.) 2014. Special Issue: Understanding Shrinkage in European Regions. Built Environment (April 8).

Costea, A. 2016. Temă de reflecție pentru candidații la alegerile locale: expoziția ‘Oraşe româneşti în declin’ la MNAC. Bloguri, May 13, 2016. Available at: http://adevarul.ro/news/societate/tema-reflectie-candidatii-alegerile-locale-expozitia-orase-romanesti-declin-mnac-1_5734e6ec5ab6550cb8e1841d/index.html [accessed 1 September 2016].

Oroveanu, M. 2004. Introduction. In: Balaci, R and Velisar, R (eds.), MNAC 2004, 19–23. Bucharest: MNAC.

Oswalt, P. (ed.) 2005. Shrinking Cities. Vol. 1, International Research. Vol. 2, Interventions. Berlin: Hatje Cantz.

Oswalt, P and Rieniets, T. (eds.) 2006. Atlas of Shrinking Cities. Berlin: Hatje Cantz.

Pallagst, K, Wiechmann, T and Martinez-Fernandez, C. (eds.) 2014. Shrinking Cities: International Perspectives and Policy Implications. New York: Routledge.

Zahariade, AM. 2016. Din spatele greu accessibil al Palatului Parlamentului [From Behind the Palace of Parliament]. In: Shrinking Cities Exhibition (catalogue). Bucharest: MNAC.