Introduction

The pervasive phenomenon of change of urban agglomerations has been insightfully described by Carola Hein, who writes that ‘The physical structure of cities can become part of a resilience narrative.’ By this term she intends ‘those stories of historic rebuilding… feeding ongoing and future efforts to build resilience’ that in turn might fold into ‘a larger feedback loop that strengthens communities’ (Hein 2019). It may be said that such a benign ‘resilience narrative’ has been the dominant story of the Yale University campus over the past century, if not longer.

Major early 20th-century facilities at Yale such as the residential colleges, the Sterling Library, the Whitney Gym, and the Law School all disrupted the unity and texture of the pre-existing campus and its immediate surroundings. Yet they did so largely in ways that allowed the entirety to participate in what might be considered a pattern of resilience in maintaining a well-tempered, articulate wholeness in the campus not often displayed in comparable projects at educational institutions. This benign practice seems not to have halted in certain important aspects of more recent architectural development at Yale. A case in point is the Yale Art Gallery complex.

When the massive four-year, $135 million restoration and revision of the Yale Art Gallery was completed in 2012, what greeted the world was not only a vastly expanded display of the university’s immense collection. One also saw in a new light the architectural masterpiece that was Louis Kahn’s breakthrough work, the New Yale Art Gallery of 1951–53 (through which one now enters the entire collection). One now grasped that this brilliant work was but the tip of an architectural iceberg built in time over many generations, reborn and made visibly present spatially and functionally. The change in perception triggered by the recent restoration has not been critically addressed. I begin with the Kahn building itself (Figures 1 and 2).

Deservedly praised for its formal and material features — open plan, luminous cylindrical staircase, tetrahedal concrete ceilings, superlative curtain wall — the building embodies temporal dimensions that remain hidden in the plainest of sight. These obscure qualities affect the meaning of the well-studied elements just mentioned as well as other details — in effect, the whole project. In particular, one salient component of the building is affected: the huge, closed brick facade on Chapel Street, a modernist anachronism and critical conundrum described in a recent Kahn monograph as ‘undoubtedly the Gallery’s most famous — and notorious — elevation’. The book’s author proceeds to explain the facade in a convoluted technical/formalist analysis characteristic of criticism regarding this aspect of the work (Leslie 2008: 70–72; compare with Cummings Loud 1989: 40). The point of departure of the present essay instead is to study this problematic facade, as well as other aspects, according to temporal criteria. In this discussion, I bracket out or temporalize the abstract, formalist terms that so dominated most 20th-century architectural analysis that it was virtually impossible to see that there were other dimensions to architecture, in particular the protean factor of time.

The Eclipse and Rebirth of Building-in-Time

It is no secret that Kahn’s work was an addition to an existing structure. Close scrutiny of their interrelationship puts the building in a new light, in which the architect emerges — at least for a few years — as a latter-day master of ‘building-in-time’, the architectural regime that according to my eponymous recent book held sway through the pre-modern European centuries (Trachtenberg 2010).1 To briefly review its methods and scope, in this formation time was not regarded as enemy to all things architectural, as in most modernist practice, but seen as an inescapable and indeed positive aspect of the thinking and making of architecture. Time, and the change that it brings, were folded into design as construction progressed in an open-ended process. No hard line existed between planning and building, or between architect and builder. There was no distinction between design and redesign: all design was redesign, beginning with the conversion of land into building site.

Rather than being reified as an absolute, immutable work of art by a famous architect-author — an ideal implanted in western architecture by Leon Battista Alberti — the building and any design for it belonged to the fungible world of things. They were thereby inscribed in the lifeworld where time was understood as an inalienable, primal condition of existence. Buildings as well as plans for them were never considered absolutely completed. It was expected that they would undergo expansion, revision, reintegration with context, including (re)combination with new and older structures. Buildings were regarded, in other words, as having resilience, a capacity to adapt to change in the lifeworld. This capacity — which in my thinking did not inhere in the building itself (as in resilience theory) but in the mentality, expectations, and practices of its lifeworld — was articulated in four unwritten but well-understood design principles, all ultimately stemming from antiquity, that constituted part of the inalienable infrastructure of architectural praxis.

The master principle, which in effect affirmed the ultimately Ovidian notion of continuous change, was complemented by three vital governing protocols. Myopic progression entailed the incremental planning of detail as construction proceeded, no building having been planned in detail from the outset. This gradualist procedure was rooted in the ancient dictum that ‘Time reveals all things’. Concatenate planning, in turn, meant simply that every design move, no matter when or at what level it occurred, would be linked with the previous state of the plan, whether by form, dimensions, proportions, alignments, materials, or detailing (a ground rule comparable to ‘symmetria’ or commensurability in Vitruvius’s De Architectura I.2.4 and III.1). To prevent the fluidity of these practices from devolving into metastatic deformation, the final, limiting principle of retrosynthesis dictated that at every stage the final design package be brought into harmony with the existing fabric (again echoing Vitruvius, here the requirement of eurythmia or comprehensive harmony, in De Architectura I.2, and VI.2) (see Trachtenberg (2017: 19).

This dynamic system was at work to varying degrees nearly everywhere. It silently enabled the making of countless masterworks, including the Abbey of Saint Denis, San Marco in Venice, the cathedrals of Siena, Florence, and Milan, New Saint Peter’s, the palace of the Louvre, and Soane’s Bank of England. Suppressed by modern architectural science and neo-Albertian modernist ideology, as noted, it went underground in the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. Slowly, beginning with movements of the 1950s and ’60s associated with Umberto Eco’s notion of the ‘open work’, there have been signs of its resurgence in recent decades, involving such initiatives as the so-called slow architecture movement (Eco 1989). Kahn’s New Yale Art Gallery, considered not in isolated, formalist perfection but as responding to a physical context with a long and not unproblematic history, as well as incorporating a new consciousness of the deep historical past, would have been an avatar of this development.

Beaux-Arts Redux: Kahn and Yale’s Incomplete Museum Complex

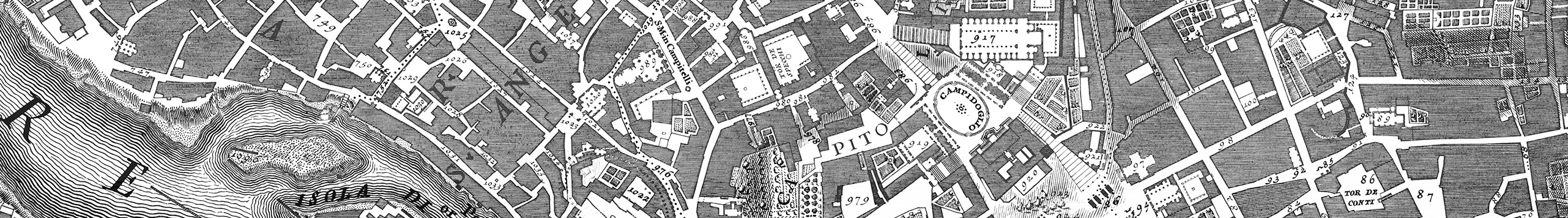

The Kahn museum was, by definition, not the first building to house the university’s renowned art collection. Art buildings at Yale had a deeper, more complicated history than is generally known. Kahn’s building was the third such structure built for the visual arts along Chapel Street (the south border of the main campus), and the fourth overall at Yale (Figure 3). It was visibly an addition to the Yale Gallery of Fine Arts built between 1926 and 1928 by the then well-known Egerton Swartwout (1870–1943) to unite the Yale art collections (this structure is now the Old Yale Art Gallery).

Yale Art Museum complex on Chapel Street. From right to left: Street Hall, in brownstone, by Peter Bonnet White, 1866; Old Yale Art Gallery, with tower and High Street Bridge, limestone, 1926–28; New Yale Art Gallery, faced with dark brick, Louis Kahn, 1951–53. Photo by Christopher Gardner, 2012.

Swartwout, trained at McKim, Mead and White, completed only five of the projected fifteen bays of his massive limestone, Italianate Gothic-cum-Beaux Arts project, together with a massive tower wing, before it was abruptly terminated, allegedly for lack of funding. His building, in turn, had been an addition to the earliest Yale art building on Chapel Street, the brownstone, Ruskinian Gothic Street Hall. Designed by Peter Bonnett White (1838–1925) on a much smaller scale, it opened in 1866 as the Yale School of Fine Arts, the first art school on an American college campus (Figure 3, at right).2 Nor was Street Hall the first Yale art gallery. In 1831 the eminent early American painter John Calhoun sold nearly 100 of his paintings to Yale and built a forbidding, nigh-windowless Neoclassical gallery freestanding in the campus for their display (eventually razed). With the transfer of the Trumbull collection to Street Hall in 1867, the Chapel Street complex was initiated. (The interiors of all three buildings were masterfully reintegrated into a continuous museum display in the above-mentioned 2008–12 revision by Duncan Hazard and Richard Olcott of Enead Architects, formerly Polshek Partnership.)

Given this setting, in the lens of building-in-time Kahn’s immediate problem was not simply what brand of modernism he would implant in the still modernist-free Yale campus, which is the way that its historical understanding is invariably framed. As the architect and his patrons evidently understood the situation, he did not have a free choice. The question intersected a difficult technical issue: how to integrate his new building with the past, the incomplete historicist fabric of the gallery complex running to the east through most of two blocks of Chapel Street. More precisely, how was he to design a novel structure within a modernist idiom that could be attached to and provide completion of a set of totally diverse, lavishly detailed buildings from another architectural age (although the closest in time had been built only two decades earlier!). This task would not have daunted architects from the pre-modern age, and evidently it did not daunt Louis Kahn. It was his genius to find the kernel of the solution within the problem itself — within the older buildings — in effect thereby ‘rediscovering’ and bringing to bear ‘lost’ methods of building-in-time. He also might be said to have activated the properties of resilience latent in the Old Art Gallery.

In Figure 3 one begins to comprehend Kahn’s way out. One need only briefly study the multistoried massing, scale, material, and color of Street Hall (on the right) to see that at the other end of the complex Kahn, in effect, has mirrored it in a generalized yet unmistakable way, with a multistory wall of dark masonry (brownish brick in place of brownstone) of almost exactly the same size and of similar color. The incomplete Beaux-Arts Italianate front is now ‘completed’, framed pseudo-symmetrically by two ‘lesser’ wings, one old, one new. Even in his first Yale work — especially in this work — Kahn is willing to ‘sacrifice’ its most prominent facade to the greater architectural good (although he turns this gesture to his own artistic ends). He observes not the letter but the spirit of decorum of traditionalist architectural protocol, thereby — one imagines — passing an important test in the eyes of his patrons. He may also have realized that there was no way to avoid making Swartwout’s massive Beaux-Arts facade the centerpiece of the ensemble. Thereby he saw that rather than fight this inherent disposition, it was far better to use the New Gallery project to transform the whole complex into a grandiose if stylistically errant and anachronistic, pseudo-Beaux-Arts composition (schematically recalling, for example, the four-block-long Fifth Avenue facade of the grandest American museum, the Metropolitan in New York). It would not detract from his own addition, to say the least.

Reinforcing this exercise in building-in-time was Kahn’s second major design task: to physically connect his new ‘bookend’ with the center. He does so with an inspired, intricate act of concatenation and retrosynthesis. Once again, his solution manifestly derives from the earlier fabric, in this case the High Street Bridge, Swartwout’s lavishly detailed structure that physically, functionally, and formally linked his gallery to Street Hall (Figure 4). With an attentive eye, keen understanding, and uncanny inventiveness, Kahn goes head to head with his predecessor, translating into modernist language Swartwout’s entire architectural game. That this was enabled by Kahn’s early 20th-century, Beaux-Arts training with Paul Cret — in the very decade of Swartwout’s building — is more than apparent.

Thus, just as the High Street Bridge is set back from the front plane of the complex and provides entrance directly to the heart of the university (the Old Campus, the Harkness Quadrangle and Tower, and the Skull and Bones hall along High Street), so Kahn extends his main Chapel Street facade in a spatially analogous, setback wing linking the new and old museums, with a stepped platform giving entrance to the campus art museum and its famous collections (Figure 5). Both structures provide usable interior space. Furthermore, although typologically and stylistically polar opposites, both old and new units are organized into four stories, with Swartwout’s motley historicist sequence of Tudor arch, colonnaded gallery, paneled clock level, and battlements being reduced by Kahn to four crisp, uniform zones. Even the stairway level of his building parallels the base level of the archway.

Yet it is perhaps in the comparable treatment of the right corners of the two solutions that we can best see Kahn’s brilliant handing of materials and detailing. This was the critical area of both designs, the actual linkage of new and old fabric. Swartwout, almost predictably, had set a medieval tower in the corner as a massive medieval ‘hinge’ between the variously medieval bridge and Street Hall. Kahn’s strategy instead is to deftly maneuver the structural elements at hand into a transitional bond (Figure 6).

First, he highlights the end wall of the Swartwout building simply by leaving exposed its provisional, red-brick wall erected to close construction when work was abruptly halted in 1928. By folding into the context of monumental architecture this rough, colorful vernacular surface, a buffer zone of contrasting properties is established between the Beaux-Arts limestone and Kahn’s refined brickwork. Yet the architect avoids direct interface of the two masonry planes (Figures 7 and 8). In the corner, between the red- and the brown-brick walls, a narrow vertical window with a finely crafted metallic framework forms a slender, perfectly proportioned ‘hinge’ of Miesian quality. It produces concatenation and retrosynthesis worthy of the finest practice of traditional building-in-time. It enables latent resilience to be materially realized.

Mirroring Antiquity: Kahn’s ‘Fire Wall’

Kahn’s new building accomplished more than the closure of an uncompleted Beaux-Arts facade and the completion of an evolving architectural program inherited from the age of eclecticism. In developing the ideas reflected in this essay I sensed an unrecognized presence in Kahn’s problematic massive wall on Chapel Street, an enigma invisible to the formalist gaze (Figure 9). To anyone versed in architectural history, such walls evoked not modernity but the architectural past — its deep past. The possibility occurred to me that the New Yale Art Gallery may have incorporated temporality in two modalities: the existential condition of time and change in which the building itself comes into being, which we have studied under the rubric of building-in-time and ‘resilience’; and the dimension of history as a cultural construct as it proliferated in Kahn’s ever-fertile imagination — history not as written but as built (a theme that Kahn scholars have sometimes explored, except regarding the Yale Gallery). Both of these dynamic categories may have been woven into the new museum’s fabric, in a complex temporal self-narrative (the spirit of which continues in many of his subsequent works).

I dwelt on Kahn’s career-altering experience at the very point when he received the Yale commission, his stay at the American Academy in Rome, and statements he made at the time (1951): ‘The architect must always start with an eye on the best architecture of the past’; ‘I firmly realize that the architecture in Italy will remain as the inspiration source of the works of the future’. Recently in Rome, wandering about one of its great sights, the Imperial Fora, with Louis Kahn on my mind, I returned to a site I had visited many times. I intuited the Kahn connection just before I saw it again: the gigantic precinct wall of the Forum of Augustus (dedicated 2 B.C.), famous among connoisseurs of Roman antiquity such as the eminent archaeologist, Frank Brown, who befriended Kahn at the academy (Figures 10 and 11). The resemblance of its form, scale, and detailing to the enigmatic Chapel Street wall was difficult to deny.

The connection was cemented when I came to consider the possible functional parallelism of the two walls in the sphere of the historical architectural imagination. The Roman structure had been a fire wall, set as a massive barrier between the glittering imperial forum and the crowded artisan quarters of the city, which posed a constant threat not only of fire but of violent mob outbursts of unrest. New Haven in the 1950s was not yet the urban nightmare of the 1960s and ’70s, yet it was no longer the sunny 1920s when the Old Art Gallery was built with its central portal and many huge windows — and more planned to come — on Chapel Street. This New Haven artery was where the campus abruptly ended and interfaced with the gritty city. It marked the steep socioeconomic divide between the elite university, with its privileged students and faculty, and the underprivileged classes as well as the plain ordinary citizens of the town (‘townies’ in Yale parlance). Of course Kahn’s ‘Fire Wall’ of the New Art Gallery would only have been symbolic, even subliminal in function, not literal protection like Caesar Augustus’s massive barrier. In fact, the adjacent side of the new gallery, on York Street, and the contiguous rear facade together presented Kahn’s brilliant variation of the mid-20th-century High Modernist glass-and-steel curtain wall. York Street is in these blocks an ‘internal’ Yale street, so that symbolically these two transparent facades were nestled ‘safely’ within the campus rather than exposed to the vagaries of the unruly city around the corner on Chapel Street. To be sure, these diverse symbolic qualities of Kahn’s building — politically incorrect even before the term was coined — went unspoken (or at least, unrecorded).

Changing Times: Kahn and Paul Rudolph after the New Yale Art Gallery

This socio-urbanistic interpretation of Kahn’s Chapel Street wall is reinforced by the peculiar character of two buildings subsequently erected in the immediate vicinity, which dance together with the gallery through time. One was Kahn’s own Mellon Center for British Art, built 1969–74 at the end of his life (Figure 12).

Times had changed again, for the worse, as many streets of New Haven devolved into a no-man’s-land in the 1960s. Kahn’s new structure was once more on Chapel Street (at the corner of High Street), but this time on the opposite side, thus physically separated from the campus. Without the Yale campus at its back, it was naked, directly ‘exposed’ to the urban dangers of those years (which were real: one of my colleagues — the late Linda Nochlin — was mugged inside a restaurant in this very block). This situation explains its peculiar architectural character, or lack thereof (on the exterior). With street fronts awkwardly proportioned, materially and formally impoverished, its look is almost that of some parking garage and/or nameless commercial building, an impression reinforced by its rental spaces on the street. The exterior completely masks its identity as a great treasure house of art with many sumptuous spaces, sponsored by a great American magnate family. The museum entrance can hardly be found, being hidden in the shadows at an unmarked corner. Paradoxically, although built in the heart of a major New England community, it documents the American flight from the city during the period: if the building could have run away, it would have.

The other work in question, of course, is Paul Rudolph’s initially notorious Art and Architecture Building, built 1959–63 in the interval between Kahn’s two galleries (Figure 13). It can only be partly understood on formalist terms, as a stylistic response to Kahn’s second breakthrough work, the Richards Medical Research Building at the University of Pennsylvania of 1957–61, now revised in New Haven into Rudolph’s more assertive ‘brutalist’ language. Rather, the key to its singular character, I propose, was its location in space as well as in time. Again, Kahn figures into the equation, for the Rudolph building was directly opposite his gorgeously refined glass-walled facades of the New Yale Gallery on York Street (Figures 1 and 2). Rudolph’s message — which turned out in his case to be miscalculated — was that antithetical, less genteel forms were possible at Yale, and could even coexist, at least across the width of a street (a lesson that Kahn took up in his own fashion in the Yale Center for British Art).

Yet the topographic key to Rudolph’s building was not so much its proximity to the gallery as its location at the extreme southwest corner of the entire Yale campus, where it sat resembling a military outpost, architecturally armed to the teeth.3 The only things missing are battlements and crenellations, which the High Street Bridge down the street already had prominently incorporated and probably could not bear being repeated. The architecture school is by far the most ‘brutalist’ of Rudolph’s works (to use Reyner Banham’s term ‘incorrectly’) in its muscular, aggressive language of form, scale, and texture. Certainly it is his only building that palpably resembles a fortress, whose entrance is fittingly de-emphasized (not unlike the way Kahn’s later Yale Center for British Art would be). The building’s ‘brutalist’ forms, in other words, here are more than merely expressive of the brute realities of material and construction, as the term was intended by Banham. The assemblage may have been unspokenly regarded by architect and client alike as perfect for an urban ‘frontier’ site in changing times (years that saw John Wayne’s 1960 film, The Alamo, about the frontier mission that served as a fortress in the bloody 19th-century conflict with Mexico).

Although with the Art and Architecture Building Rudolph succeeded in entering the annals of architectural history, it experienced a frightful immediate reception. The building was seen as having committed an architectural blunder — several — if not a crime, which Kahn took care not to repeat in the Mellon Center (apart from its anomalously obscure entrance). Yet despite Rudolph’s architectural vehemence and his renunciation of overt inflection to Kahn’s original building or attempting to achieve a balance, a mysterious ying-yang dialectic can be sometimes sensed between the two structures. Both were masterworks in not only their assertive form language but their resilient engagement with time and temporality in a bygone era of American architecture.

Conclusion

Resilience at Yale, in the works studied by this essay, would have sustained a keen architectural coherence of the forms and relationships, scale and materials of buildings, at the same time transforming the architectural envelope with bold new spaces and monumental ensembles. In this perspective, the mid-to-late 20th-century development of Yale’s art complex on the south edge of the campus, where it interfaced directly with gritty downtown New Haven, drew on an inherent resilience residing in the campus at large. These recent campaigns also were enabled by the spirit of building-in-time, and they incorporated the self-possessed agency of two brilliant architects, Paul Rudolph and especially Louis Kahn, who was trained in the pre-modernist, Beaux-Arts tradition that tended to foster ‘resilience’, unlike mainstream modernism and its intolerance of history. For a card-carrying modernist, to the degree that a building was ‘resilient’ and could be adapted and successfully reused, it stood in the path of architectural progress. Resilience, by setting a path of compromise and adaptation, in effect was the enemy of progress.4 It would appear that for Kahn and Rudolph resilience was instead the higher goal.

Notes

- The concept of building-in-time is encapsulated in Trachtenberg (2011) and Trachtenberg (2014). [^]

- For an overview of Swartwout’s design for the Yale Art Gallery and its history, see Kane (2000). [^]

- In 1999/2000 the Yale School of Art, which had shared Rudolph’s building with the architecture school, was moved to the former Jewish Community Center building beyond the former campus confines, at 1156 Chapel (a ‘standard’ modernist structure built by Kahn in 1952), renamed ‘Green Hall.’ [^]

- After completing this article, it came to my attention that Vincent Scully has briefly noted in ahistorical, formalist terms the interrelated row of buildings on the north side of Chapel Street, drawing the conclusion that ‘it is an instructive sequence urbanistically, in that it shows a large part of what urban architecture really is: a creation of interior and exterior spaces and, most of all, a continuing dialogue between generations which creates an environment developing across time’ (Scully 1988: 203). [^]

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Cummings Loud, P. 1989. The Art Museums of Louis I. Kahn. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Eco, U. 1989. The Open Work. Trans. A. Cancogni. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hein, C. 2019. Scales and Perspectives of Resilience: The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima and Tange’s Peace Memorial. Architectural Histories. In press.

Kane, PE. 2000. Egerton Swartwout’s Gallery of Fine Arts at Yale University. Yale University Art Gallery bulletin, 69–87.

Leslie, T. 2008. Louis I. Kahn. New York: Braziller.

Scully, V. 1988. American Architecture and Urbanism. New York: H. Holt.

Trachtenberg, M. 2010. Building in Time: From Giotto to Alberti and Modern Oblivion. 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Trachtenberg, M. 2011. Ayn Rand, Alberti and the Authorial Figure of the Architect. California Italian Studies, 2(1). Retrieved from: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6ff2m22p.

Trachtenberg, M. 2014. To Build Proportions in Time, or Tie Knots in Space? A Reassessment of the Renaissance Turn in Architectural Proportions. Architectural Histories, 2(1): Art. 13. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/ah.bp

Trachtenberg, M. 2017. When Did the Renaissance in Architecture Begin? From Vasarian Historiography to Panofskian Mythography. In: Payne, A (ed.) Companion to the History of Architecture, Volume I, Renaissance and Baroque Architecture, 1–37. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.