Last June, at the biannual meeting of the European Architectural History Network (EAHN) in Tallinn, I officially took over the editorship of Architectural Histories from Maarten Delbeke, founding editor in chief. I thank Maarten Delbeke for his veritably Herculean efforts to set up and develop the journal, whose first volume dates to 2013, handing his role over only after nursing the journal through its first growing pains and after having secured a more stable financial basis for it. Publishing in Architectural Histories is free. Because of the continuous support from the EAHN and, since 2018, the Open Library of Humanities, there are no financial barriers for authors who submit an article to the journal. I also want to recognize the energy and professionalism of our first editorial assistant, Nele de Raedt, qualities that Christian Parreno carried forward from the moment he took over.

One could say that with the appointment of a new generation of editorial board members and officers of the EAHN, the journal and the network have both moved beyond the first stage of inventing a tradition, to borrow from Eric Hobsbawm. The journal’s early beginning was confirmed with the publication last June, during the Tallinn meet-up, of the Special Collection ‘On the Meaning of “Europe” for Architectural History’, celebrating the EAHN’s tenth anniversary in 2016. The calls for papers, the annual business meetings, the themed conferences, the conference dinners, the keynote lectures, the interest groups, the by-laws of the EAHN, the blind peer-review reports, the indexing of the journal, the EAHN Publication Award for best article in Architectural Histories—all are part of the formalization and ritualization of a set of practices that are governed by rules, which, as Hobsbawm put it, ‘seek to inculcate certain values and norms of behaviour’.

With the 2018 volume being the first to appear under my responsibility, I have continually been confronted with rules and guidelines, and, more importantly, with the ‘values and norms’ of scholarly ‘behaviour’ that underlie them. What values and norms does Architectural Histories stand for? It is a question that comes up in almost every meeting. What makes a good research article? What are our norms for peer review reports? How can Architectural Histories reflect the current state of research of our field? What role can the journal play in our academic thinking and working practices? Let me share with you some of the recurring questions and issues that I noticed over the past year, because of my increasing involvement with the ritual that we call academic publishing.

The Digital Medium: Limitations and Possibilities

One feature I have observed about the digital medium is that it so far has not fundamentally altered the ritual of academic publishing. The well-rounded scholarly text — be it a research article, field notes, or a review — remains at the heart of our academic work, shaping it both literally and conceptually. The possibilities of the digital features of Architectural Histories are valuable, though still rather limited. They can be found in the ease of use (like jumping back and forth between notes, sections, and the main body of the text, or enlarging illustrations) and in the ease of organization: the flexibility of the medium allows for articles to be published at any moment, and for themed issues to appear in phases. With one click, at any moment, all articles of a themed issue can be grouped together. Also, the digital allows for the publication of supportive materials such as virtual models or reconstruction videos, as in Maekelberg and De Jonge (2018).

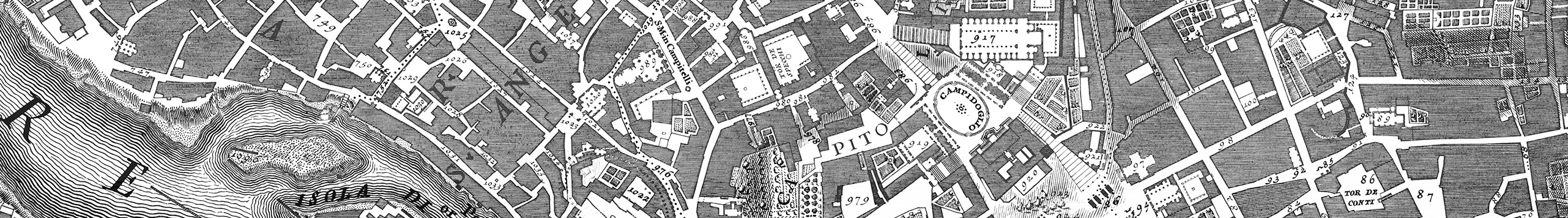

However, the wealth of possibilities that the digital realm has to offer — links in notes that provide direct access to archival sources or databases, interactive models, maps, and images that together reconstruct historical, present, or imaginary situations and give insight into a reconstruction’s underlying design and selection process — is restricted by technical and financial constraints. The publisher of Architectural Histories, Ubiquity Press, for example, works with highly standardized digital formats that leave little room for experimentation, but at the same time, because of their time and cost efficiency, make the publication of the journal affordable. I am convinced that it is only a matter of time before these constraints disappear, since we are still in the early stage of developing the full possibilities of digital publishing.

The Peer-Reviewed Research Article: A Treasure and a Constraint

The relative conservativeness of the journal, despite its digital format, is connected with its status as blind peer-reviewed, scholarly journal. In today’s ritual of academic publishing, the peer-reviewed research article is both our treasure and our constraint. With academic freedom and integrity being increasingly under pressure worldwide (while writing this editorial it’s in the news that the Central European University is being forced out of Budapest), we should treasure the peer-reviewed article for reflecting the highest standard of our critical and creative thinking. Together with scholarly books and essays, research articles advance our knowledge of architectural history in the broadest sense, mining new sources and confronting us with new methods and ideas. In addition to these public texts, it’s the privilege of editors to have access to peer review reports, which can generate incredibly rich and informed discussions with authors and among editors. I find great joy and learning in being part of an editorial board and part of this process of knowledge-in-the-making.

At the same time the academic article could be seen as our constraint, with its central position in the ongoing formalization and bureaucratization of academia according to the publish-or-perish principle. To comply with publication norms for scholarly articles is paramount for every next step on the challenging trajectory of an academic career. Discussions within the editorial board about experimenting with new publication forms, such as a public peer review process or more journalistic articles, are hampered by norms for the further indexation and ranking of Architectural Histories. Within the academic limits, however, a greater variety of scholarly texts is possible. It is my aim to develop a more diverse content for Architectural Histories that better reflects our broad commitment as academics.

Variety and Diversity in Scholarly Texts

This fall I have reinvigorated the journal’s initial engagement with architectural criticism (the first volume in 2013 had thirteen reviews, against seven research articles). Now, with Libby Merrill and Wouter Van Acker as pre- and post-1800 review editors respectively, it is our aim to publish some fifteen to twenty reviews a year (compiled together in four Review articles), covering a wide array of topics. In addition to the classic book and exhibition reviews (including the new medium of the VR exhibition), I also aim to publish evaluations of the built environment, looking at recent buildings, urban projects, landscape designs, and restoration projects. The architectural historian’s unique strength, to provide a historically informed analysis of contemporary architectural phenomena, is surprisingly underused. Architectural journalism is flourishing, for better or for worse, with online platforms, such as ArchDaily, Dezeen, and The Guardian’s Cities section, to name just the obvious, and traditional architectural journals, such as Architectural Review and Arch+, demonstrate an increasing interest in the history and theory of architecture. But the scholarly, in-depth critique of today’s built environment is underrepresented, while it could make an important contribution to contemporary architectural culture.

A greater diversity of content will also be attained because of tightening the journal’s connection with the EAHN. Besides the Field Notes reporting on the bi-annual meetings, I aim to have a Position Paper on every themed conference. This enables the convenors to set out the central theme in a more elaborate and provocative way than a call for papers allows for. In addition, the EAHN’s Interest Groups are encouraged to report on their work and debates. The first group to do this, Architecture and the Environment, set a high standard, with their thought-provoking Field Notes, gathering fourteen positions ‘that confront the imminent environmental challenges as collective intellectual enquiry, but from varied geographical, historical, and theoretical standpoints’, as Sophie Hochhäusl and Torsten Lange explain in their introduction. Lastly, Stelios Giamarelos has been appointed Interviews editor, to develop in-depth interviews with scholars whose personal visions we believe will shed a new light not only on our past and current practices as architectural historians, but also on professional issues that are at stake, both within and outside of academia. What does our profession stand for, and where do we go from here?

English as Lingua Franca

My commitment to a greater diversity of articles, reflecting the plurality of architectural history’s subject matter and modus operandi, strengthens the course that Architectural Histories has pursued from the outset. By contrast, the original aim, to represent the linguistic and cultural diversity of contributors and readers, proved too ambitious, both practically and financially (e.g., organizing peer review, editing, and copy-editing in multiple languages). Even more important is the fact that the lingua franca of an international peer reviewed academic journal is inevitably English. While earlier generations of English intellectuals taught themselves Italian in order to read Dante in the original (to paraphrase Reyner Banham, who himself learned to drive in order to read Los Angeles), today’s non-native English speakers must not only read, but also write and teach in English in order to be part of the international academic community. Werner Oechslin’s pre-eminent international summer courses and conferences represent one of the last refuges of the European academic habitus, where German, English, French and Italian are used as the working languages.

Native English speakers may find it difficult to imagine the greater efforts and time investment required to express oneself in a language that is not one’s mother tongue. Nearly all articles from non-native English speakers need significant extra editorial support to meet the publication standard. At the same time, many of these authors have access to unique sources and materials that are only available for those who can read and contextualize them. A look through only the past two volumes of Architectural Histories reveals a geographical and substantive scope that would have been unimaginable in even the recent past: the approach of Athens-based Atelier ’66 to post-war incremental housing, architectural discourse in Mao’s China, travel accommodations in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany between the 17th and early 19th centuries, the origins of architectural craftsmanship in ancient Greece, early 20th-century customer magazines promoting the single-family house in Germany, Sljeme chain-motels along the Adriatic highway, architectural knowledge production by settlers of European origin or descent in Mozambique and South Africa, the Hispanic debate on the late 18th-century Spanish church interior, the whereabouts of the dividing line between Europe and Turkey, the tourist landscape of postcolonial Cyprus, and the international education of 20th-century architects from Colombia.

By default such articles question existing theories, methods, discourses, and historiographies by demonstrating an infinitely more complex architectural realm. They offer alternative readings of long-existing theories and concepts such as (post)colonialism, feminism, transnationalism, heritage, and environmentalism. Despite the arguable and disciplining ritual of international (read Anglo-American) academic publishing, I believe that a common ‘set of practices’, including the use of English as our lingua franca, proves to be crucial to overcome geographical and cultural boundaries. Or rather, they help to acknowledge these boundaries and make them productive in our research. The title of the journal, Architectural Histories, is the best and constant reminder of this scholarly pursuit.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.