Theming the Euro: Issues of Style, Matters of State

When bankers get together for dinner, they discuss Art.

When artists get together for dinner, they discuss Money.

Oscar Wilde

The first step toward designing a common European currency was a matter of ‘theming’. The challenge was to identify an overarching theme that spoke to the idea of a united Europe. While the initial instinct was to lean on Europe’s vast historical heritage, the past was a minefield, a history of conflict, mostly colored by the dynamics of the state. How could an entity that had been built to put an end to that history also manipulate it and extract an image of unity?

The project of the euro began in earnest after the signing of the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, the agreement responsible for the creation of the European Union (Mulhearn and Vane 2008; Chang 2009; Heinonen 2015).1 In the same year, the governors of the central banks of the states involved in this process established the Working Group on Printing and Issuing a European Banknote. Pursuing the goal of monetary unification also required a new supranational institution. The intergovernmental committee of bank governors that had supervised financial matters since the 1960s had to be replaced by an organization that could properly oversee the transition toward a common currency. The European Monetary Institute began operations in 1994, paving the way for the establishment of the European Central Bank, which took over its functions in 1998.

Upon meeting in November 1994 in Basel to discuss how the design of the new banknotes was to be organized, the Working Group on Printing and Issuing a European Banknote decided to assemble a team of ‘experts from appropriate disciplines, including historians, art experts, psychologists and both banknote and general design professionals’ that could come up with a series of possible themes for the euro notes (TSAG 1995: 3). This team took the name of Theme Selection Advisory Group.

The group comprised fifteen members. As they had to be nominated by the central banks, most of these members were the heads of the design section, the graphic designers or the keepers of the collections of said banks. There was only one art historian: Jaap Bolten, an expert on Dutch prints and drawings from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

As evidenced by the confidential report sent to the European Monetary Institute in May 1995, the Theme Selection Advisory Group considered eighteen themes for the new banknote series and ranked them from best to worst (Figures 1 and 2). The report included a detailed description and a ‘critique’ of each theme, illustrating its advantages and disadvantages. One of the main criteria was that of ‘acceptability’: the group used the hypothetical example of a banknote bearing a portrait of Napoleon to show how certain images would be accepted in some countries (one in particular) and rejected in others (TSAG 1995: 4).

The preferred theme was called Ages and Styles of Europe. The proposal was to have ‘portraits of ordinary men and women’ on one side of the banknotes and ‘architectural styles’ on the other. Both the people and the architecture were to be ‘completely nameless’, so as to avoid possible ‘traps and pitfalls’. The goal was to ‘convey, without specific reference to any given building, a clear message on the architectural richness and unity of Europe’ (TSAG 1995: 7).

Ages and Styles of Europe was not the only theme that engaged with architecture. Among other proposals was a particularly significant theme called Monuments, ranked thirteenth in the report (Figure 3). It suggested representations of iconic buildings, such as the Parthenon and the Eiffel Tower. The advisors compiled a long list of disadvantages, noting that only a handful of member states would be represented, that most monuments convey different symbolic messages in different countries and, most importantly, that very few monuments are linked with ‘the idea of Europe’ (TSAG 1995: 37).

It is quite difficult to find a monument in Europe that was not conceived according to or retroactively steeped in some kind of nationalist narrative (Hobsbawm and Ranger 1993; Choay 2001). The advisory group argued that the only way to avoid these problems was to illustrate ‘styles of monuments’ rather than specific buildings, which was essentially the idea of the first theme (TSAG 1995: 37). From the beginning of this process, stylization was identified as the operation that could unlock the iconographic labyrinth.

The logic of stylization, however, had itself been historically rooted in the dynamics of nation-building throughout most of Europe. While stylization sprang from the universalizing ethos of the Enlightenment and was initially put to work as a method for systematizing the past (as exemplified by Winckelmann’s Geschichte), it took on additional meaning at the beginning of the nineteenth century, becoming a tool for the construction of national representations (Harloe 2013). As noted by Barry Bergdoll, this was the period in which ‘issues of style became matters of state’ (Bergdoll 2000: 141).2 A definition provided by Heinrich Hübsch in the pamphlet In What Style Should We Build? is quite telling: ‘Style means something general, applicable to all buildings of a nation’ (Hübsch 1992: 66).

Feature Selection: Political Correctness and Postmodernization

The second phase in the development of the euro revolved around an intricate debate on which ‘features’ could form the overarching idea of the selected theme. Countering a pattern that had long characterized the design of banknotes, the common currency turned away from anthropomorphic representation, which, unlike architecture, was ill-suited to the logic of stylization.

In June 1995, the Working Group on Printing and Issuing a European Banknote accepted the recommendations of the advisory group and decided to move forward with the theme Ages and Styles of Europe. But, at the same meeting, the working group determined that a design competition based on this theme required additional preparatory work. The result was the creation of a second team, called the Feature Selection Advisory Group, which this time needed to include ‘members with specific experience in art and architectural history’. The group had three and a half months to produce ‘a written report with appropriate illustrations’ on the aforementioned theme (FSAG 1995: 14).

Given the tight schedule and the fact that, again, the ‘experts’ needed to be nominated by the national central banks, twelve out of fifteen theme group members also took part in the Feature Selection Advisory Group. Italy and Finland opted for change and nominated two art historians: Nicole Dacos Crifò from the University of Siena and Aimo Reitala from the University of Turku. However, despite the nature of the theme, the group included no architectural historians and had only two members with a degree in architecture: José Pedro Martins Barata, the president of the Portuguese Design Center, and John Voncken, an architect who worked for the Service des Sites et Monuments Nationaux at Luxembourg’s Ministry of Culture.

The first task was to perform the act of periodization implied by the theme Ages and Styles of Europe (Figure 4). As the European Monetary Institute had already determined that the new currency would have seven denominations, the group had to divide the historical matter at hand into seven ‘ages and styles’ (Heinonen 2015: 39–53). The final report acknowledged that the group had initially identified ten periods, but then found a way to cut it down to the required number: ‘Classical, Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque and Rococo, iron and glass architecture, and modern architecture’ (FSAG 1995: 3).

Although most members of the feature group had also been part of the theme group, the former ended up challenging some of the principles outlined by the latter. The main bone of contention was the notion that the features on the banknotes had to be ‘anonymous’. Such skepticism found its way into the introduction to the report: ‘Although opinions are divided among the experts, the majority view is that the European banknotes should depict parts of real buildings; the artists and graphic designers should not be allowed to produce a freely invented representation of an architectural style’ (FSAG 1995: 2).

The group also raised another fundamental objection that the European Monetary Institute came to share. As previously noted, the concept of Ages and Styles of Europe was to combine representations of architectural styles with portraits of ordinary people ‘taken from European paintings, drawings, sketches, etc.’ The advisors, however, pointed out that it was impossible to ‘check the political correctness’ of these figures (FSAG 1995: 9). Thereafter, the entire design process was steered away from portraits and centered on architecture alone. In fact, when the euro was put into circulation in 2002, one of its most innovative features was the absence of human representation.

In his research on currency iconography, Jacques Hymans assembled a database of more than a thousand European banknotes, from the early nineteenth century to the 1980s and showed how this iconographic space had been dominated by human figures, which had evolved over time from mythical symbols of states in flowing robes to portraits of famous individuals, such as painters and composers (Hymans 2004). One of the most common approaches adopted the ‘masters and masterpieces scheme’, which featured images of ‘great men’ on one side of the banknote and related ‘great buildings’ on the other (Hymans 2004: 21). This scheme is also found in the banknotes of other federal systems to which the European Union is often compared. For instance, the US dollar features images of presidents and prominent public buildings, such as the White House and the Lincoln Memorial. Another significant example is the Swiss Confederation, which in 1995 introduced a new banknote series centered on famous personalities in the arts and their work: the first note in the series (10 francs) featured a portrait of Le Corbusier on one side and drawings of his Chandigarh project on the other (Figure 5).

Le Corbusier’s 10-franc note, 1995. This banknote was discontinued in 2017, due to protests regarding Le Corbusier’s affinities with fascism and the Vichy government. It was replaced by a note aiming to represent Switzerland’s ‘organizational talent and punctuality’. Source: Swiss National Bank.

In a speech titled ‘The Euro: A Currency without a State’, the first chief economist of the European Central Bank, Otmar Issing, defined the euro as ‘a unique experience in history’, considering that, on the one hand, it was based on a supranational monetary order and, on the other hand, political union was limited and sovereignty remained predominantly national in many policy areas (Issing 2006). Due to this uniqueness, it is difficult to identify other banknotes that could truly serve as a basis for comparison.

According to the International Organization for Standardization, the euro is not alone in the class of ‘supranational currencies’ — also known as ‘X currencies’.3 All the other members, however, are currencies that refer to groups of former British or French colonies, such as the East Caribbean dollar, the African franc and the Pacific franc. The design of their banknotes reflects tensions associated with the process of decolonization rather than the struggle to achieve a common, supranational identity. For example, since its introduction in 1965, the East Caribbean dollar has always featured portraits of Queen Elizabeth II.

Looking for another term of comparison, one may be compelled to consider two countries whose paths towards unification were long and difficult and, in the end, were able to bring together a multitude of heterogenous entities: Italy and Germany. The first banknote series of both the Italian lira and the German mark, issued in the 1860s and 1870s respectively, speaks a very similar language. In both cases, the newly established rulers used the banknotes as an opportunity to convey their own message, ignoring the diversity of the previous situation in favor of a singular representation of power. The designs were dominated by features such as portraits of the king and the kaiser, the armorial bearings of the House of Savoy and the German imperial crest and personifications of Italy and Germany in the form of female figures.

In the case of Germany, however, a different strategy was used for coins. In fact, all coins above one mark had a standard design for the reverse (the eagle insignia of the Reich), while each Land could choose its own design for the obverse, which usually consisted of a portrait of the local ruler or the city’s coat of arms.

The distinction between obverse and reverse is significant because, more than one hundred years later, the same logic was applied to the euro coins. Unlike the banknotes, the coins have a multifaceted iconographic apparatus: they have a ‘common side’, which is the same in all countries, and a ‘national side’, which can be decided by each member state individually, provided that it respects the basic criteria defined by the European Monetary Institute (Raento 2004).

The decision to follow such an approach was taken at the Ecofin summit of April 1996 — the council of the economics and finance ministers of all European member states (CEC 2005). Several motivations were given to support national representation on euro coins, the main argument being that it could facilitate the transition toward a common currency in the eyes of many citizens. But there were also technical-juridical problems: for example, Belgium had a constitutional obligation to feature a portrait of the king on its coins.

Notwithstanding the opposition of both the European Monetary Institute and the European Commission, this two-sided scheme was eventually approved, after the ministers had accepted the compromise that the national designs would at least be framed by a circle with the twelve stars of the European flag. As noted by Oriane Calligaro, this compromise is emblematic of the constant tension between the two faces of European integration: the supranational side and the intergovernmental side (Calligaro 2013; Toemmel 2014). Unlike banknotes, coins had to be minted and issued by the national banks; therefore, they were partly under the jurisdiction of the member states.

As a result, one side of the euro coin varies from state to state. Several states chose to occupy this bastion of national pride with representations of architectural monuments. For example, Germany used the Brandenburg Gate on its 10-, 20- and 50-cent coins, Italy used the Colosseum on its 5-cent coin, and Austria used Olbrich’s Secession Building on its 50-cent coin. But there were also numerous portraits of ‘great men’, such as Mozart, Dante, Cervantes and several monarchs.

The specificity of these representations was in sharp contrast to the generic character of the common side, which featured a sequence of maps of Europe designed by Luc Luycx. A designer at the Belgian Royal Mint, Luycx made the case that ‘a Europe-wide currency had to be neutral, the graphics could not be too specific; if I had opted for portraits of famous people or architectural monuments then one country was bound to be more strongly represented’ (Luycx 2001).

The reiteration of traditional motifs in the only iconographic space that was still up to the states makes the direction taken by the European Monetary Institute with the banknotes seem even more ground-breaking. In Hymans’s analysis, the fact that the euro banknotes were ‘uninhabited’ was associated with postmodernization and the turn against grand narratives and their heroes — a reading that aligned with a significant section of the discourse on European integration (Hymans 2004: 10; Van Ham 2001).4 Notably, in the influential pamphlet The Postmodern State, published in the same year as the euro design competition, Robert Cooper described the European Union as ‘the most developed example of a postmodern system’ (Cooper 1996: 26).5

The final report of the Feature Selection Advisory Group reveals a certain reluctance to engage with the term ‘modern’. In the aforementioned periodization for the euro banknotes, the final section started in the 1930s and was devoted to modern architecture (with a lower case ‘m’). As evidenced by the report, the group ‘discussed the modern or last banknote at length’, and several members suggested ‘that the modern period be replaced by another, previous period’. In the end, the group considered that, since the European Union and its institutions were conceived in the twentieth century, one banknote design had to represent this period (FSAG 1995: 9).

The concept of modernity is key because, historically, it underpinned the relationship between architecture and the state (Figure 2). In the transatlantic context and beyond, the trajectory of modern architecture constantly paralleled that of the modern nation-state. Writing when architecture’s association with the state was particularly strong, at the height of the Fascist regime in Italy, Giuseppe Terragni made the argument that ‘architecture is a state art’ (Terragni 1931). This declaration of interdependence spoke to a connection that had been crystallizing in Europe for more than three hundred years. Though its roots certainly go deeper, a point of reference can be identified in the seventeenth century, when the modern state system took form in Westphalia. In this framework, architecture played a key role in the process of nation-building, while the state operated as the primary force and authority behind the production of architecture.

This balance of power started to change among the debris of World War II, accompanied by two dynamics that are rarely discussed together. On the one hand, the process of European integration led to a forceful questioning and rescaling of statehood. The Treaty of Paris, the act that officially kickstarted this process in 1951, was an explicit attempt to move past the modern state system and its many problems, as the consequences of nationalism were still very much etched in everyone’s memory.6 In Cooper’s analysis, a key aspect of this transition was a collective stance against the development of grandiose self-images (Foley 2007). On the other hand, what is known as the modern movement in architecture began to be radically challenged.

While most European states were transferring power to a new supranational system that political scientists defined as postmodern, those who heralded a postmodern turn in architecture failed to see the connection and, to this day, these two discourses have not intersected. As an attempt to go beyond the modern nation-state, European integration was a process of both supranationalization and postmodernization. How did it engage with a discipline — architecture — that had been deeply entrenched in the very structures it aimed to overcome? In the area where European integration went the furthest, the area of monetary unification, architecture was immediately brought to the fore. The way the euro design competition was set up, however, shows that this embrace was accompanied not only by a resolute effort to cleanse architecture from its national liaisons, but also by an attempt to obscure the ‘modern period’ from the genealogy of European architecture.

History-Building: Copy, Cut, Paste, Delete

The set of guidelines, checks and balances defined in the preliminary stages of the euro project was ultimately intended to inform a selection of concrete examples that could appropriately represent the chosen ‘ages and styles’. Although the operative goal was to put together a series of models that could serve as the basis for the required act of stylization, the by-product of this process was a more articulated document that shines a light on the difficulty of dislodging history-writing from nation-building.

Following the mandate of the European Monetary Institute, the Feature Selection Advisory Group ended up producing a two-part document — half text-based and half image-based. The former was attached to the final report under the bureaucratic label ‘Annex 4’ and comprised a description of the seven architectural styles. Each section included an introduction to the period at hand and a selection of representative buildings and features that are commonly associated with that style, and ended with an overall explanation for those choices (FSAG 1995).

The descriptions focused on architectural types and elements. For example, the Classical period was associated with a selection of types (temple, aqueduct, theater etc.) and elements (column, base, entablature etc.) that could be easily abstracted from any specific building. In the areas that required specificity, namely the selection of representative examples, an effort was clearly made to pick buildings that were as politically correct as possible and conveyed the fewest nationalist messages.

In the chapter devoted to modern architecture, the advisors called into question the acceptability of most ‘buildings in the Bauhaus style’, which they associated with the failures of social housing in the banlieues of many European cities (Figure 6). On the contrary, they thought that Alvar Aalto’s Finlandia Hall was ‘a most appropriate — albeit lesser known — symbol of European peace and unity’, emphasizing the fact that the 1975 European Convention on Security and Cooperation had been signed in that building (FSAG 1995: 22).

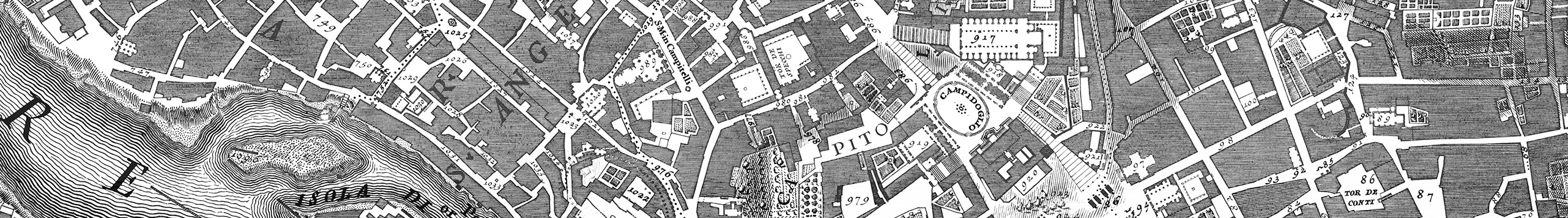

Along with these writings, the feature group also assembled a selection of images that, according to the advisors, could represent the seven periods and styles. Unlike the textual descriptions, this 116-page document was later attached to the design competition brief, under the name ‘Appendix 2’ (Figures 7 and 8). It consisted of a sequence of 108 black-and-white images of buildings, sculptures, paintings, drawings and photographs, ranging from the eighth century BC to the twentieth century (FSAG 1995).

In trying to understand how this document was constructed, two interviews, those with Jean-Michel Dinand, the executive of the European Monetary Institute who oversaw this process, and John Voncken, the aforementioned architect, who represented Luxembourg, were particularly important. As the only architect in these advisory groups, Voncken played a key role in the selection and definition of the final design. During our conversation, he recalled going to a meeting in Brussels after the competition and realizing that he was the only remaining counselor: ‘From that moment on I became a little nervous … I was in fact the only one to give the OK for all the banknote designs’ (Voncken 2020).

According to Voncken, every member of the Feature Selection Advisory Group contributed to the construction of Appendix 2, although the three art historians (Jaap Bolten, Nicole Dacos Crifò and Aimo Reitala) took on a leading role. Dinand recalled that, at the first gathering in June 1995, everyone was asked to go through their own manuals of art and architectural history at home, select a series of images and make photocopies. At the following meeting at the Eurotower in Frankfurt, each photocopy was the object of a collective discussion: ‘as a result of the tour de table, each image was either retained or discarded’ (Dinand 2020). The janitor who emptied the trash bins of the EMI office that day must have been the only person who saw those discarded, alternative histories, made of features that were considered too nationally biased or politically incorrect.

No single book of art or architectural history can be identified as the predominant source for the selected images: they were taken from a multitude of books, as more than ten people pitched in and brought their own proposals. The images were cut and pasted onto A4 pages that had been previously set up with the corresponding captions and headers. Each page was then photocopied again to make it flat and run through a hole-puncher, so that it could be put in a binder. The manual labor that went into making this collage was performed by the staff of the Working Group on Printing and Issuing a European Banknote.

Although the art historians in the room were certainly used to working with slides, Voncken did not recall anyone handling or projecting slides during these meetings. The way Appendix 2 is structured, however, seems to align with the logic of the slideshow, which is based on the construction of a series of images, arranged in a linear progression and made homogeneous by a common standard framework (in this case, an A4 page).

But this document also had an operative character, in the sense that it was imagined as a concrete tool for the participants of a competition, who were asked to use these images as models for their own design proposals. One may be tempted to compare it to a model-book, a medium that goes back to the Middle Ages, when artists relied on compendiums of motifs passed from one generation to another, ready to be inserted into paintings and other artworks (Giles 2014). In the case of the euro design competition, however, the designers were not allowed to copy the assigned motifs and, instead, needed to ‘stylize’ them.

Overall, in an attempt to provide a system that could guide and channel the design of a new banknote series, the Feature Selection Advisory Group produced an illustrated survey of European art and architecture based on the logic of stylization, at a time when such an endeavor would have been widely regarded as anachronistic, to say the least. It was a history through images, made by many hands, informed by a multitude of ideological considerations and framed so as to discourage the reader from approaching it with a naïve or innocent eye (Gombrich 1960).7 This body of images was explicitly presented to its intended audience (the participants of the competition) as material that was guilty of national bias and therefore needed to be transformed into something else.

A significant amount of naïveté, however, lay in the failure to recognize that, along with stylization, the production of history had also been entangled in the web of the nation-state. Since the nineteenth century, the construction of national styles had been accompanied by the writing of national histories: the two practices went hand in hand. As noted by Patrick Geary, ‘the modern study of history was conceived and developed in the nineteenth century as an instrument of European nationalism’ (Geary 2002: 15).

Eric Hobsbawm put it more directly:

Historians are to nationalism what poppy-growers in Pakistan are to the heroin-addicts: we supply the essential raw material for the market. Nations without a past are contradictions in terms. What makes a nation is the past, what justifies one nation against others is the past, and historians are the people who produce it. So, my profession, which has always been mixed up in politics, becomes an essential component of nationalism. (Hobsbawm 1992: 3)

In our case, the question is, how do historians relate to supranationalism? The easier option is to Photoshop the past, distorting it just enough to obscure its national connotations, while maintaining and taking full advantage of its aura. In essence, the task of the euro competition was to turn a history of buildings (Appendix 2) into a history without buildings, replacing images of specific objects with generic representations of style. The design of the euro was meant to draw from the past, but at the same time, every site-specific — meaning, state-specific — reference had to be concealed. Getting rid of buildings was thought to be the most effective way of solving the problem of national bias. However, in addition to stylization, the very act of building historical narratives of this genre was itself deeply embedded in a conceptual framework of nation-building, especially in Europe.

Design Selection: Negotiating the Public

In February 1996, shortly after the submission of the final report of the feature group, the euro design competition got under way. This marked a transition from setting up rules and choosing models to evaluating and ultimately selecting actual designs. The process was characterized by multiple, increasingly complex levels of evaluation, ranging from a jury panel to an opinion poll, from print and television media to the public at large.

The competition was not open to everyone: the European Monetary Institute asked each central bank to nominate a minimum of one and a maximum of three participants. In the end, twenty-nine participants (both individuals and teams) submitted proposals. While many of them were employees of the national banks, there were also nominees from the private sector (working for such well-connected companies as De La Rue Currency and Komori Currency Technology) and a few independent designers.8

Meanwhile, the Working Group on Printing and Issuing a European Banknote assembled a jury of ‘internationally renowned experts in marketing, design and art history’, which met on 26 September 1996 to evaluate the proposals (ECB 2003: 8). The group included two art historians, along with jurors from the fields of graphic design, communications, marketing, advertising, broadcasting, curatorship, industrial design and psychology, many of whom came from academic institutions.

The task of the jury was to draw up a shortlist of ten proposals. Commenting on the decision of the jury, the chief cashier of the Bank of Finland, Antti Heinonen (who later became director of banknotes at the European Central Bank), underlined the fact that ‘there were few portraits in the various series it selected because even the slightest similarity to a real person could have been interpreted as favoritism towards a certain nationality’ (Heinonen 2015: 62).

As soon as the jury had completed its work, the European Monetary Institute moved to the second, decisive phase of the evaluation process and hired EOS Gallup Europe (the overseas branch of Gallup, a major American analytics company specializing in opinion polls) to conduct a ‘qualitative study’ aimed at evaluating ‘the reactions of the public and certain professionals who handle daily a large number of banknotes’ to the shortlisted designs (EOSGE 1996: 2).9

Throughout October 1996, EOS Gallup Europe teamed up with multiple ‘survey and research companies’ in the fourteen countries that were expected to join the euro and interviewed almost 2,000 people. The findings were presented in a report sent to the European Monetary Institute on 6 December 1996 — a report taken very seriously by the Working Group on Printing and Issuing a European Banknote. In fact, the winner of the competition ended up being the proposal that performed best in Gallup’s survey.

At a meeting in Frankfurt on 3 December 1996, having weighed the jury’s evaluations and the survey results, the Council of the European Monetary Institute chose the proposal submitted by Robert Kalina, the banknote designer of Austria’s national bank. A detail that is worth noting is that Kalina, in addition to working for the said bank, was also its nominee for both the theme group and the feature group, so he participated in the entire process leading up to the competition. Somehow this was not against the rules and none of the other designers complained.

An alumnus of the Hochschule für Graphische Künste in Vienna, Kalina began to work for the Austrian national bank in 1976 and designed all the Austrian schilling banknotes issued after 1982 (ECB 2003: 82–83). Notably, all his schilling designs were based on the ‘masters and masterpieces’ scheme. But Kalina’s proposal for the euro banknotes went a different route. First, he was among the designers who fully embraced the architectural theme and did not include any human figures. Second, rather than engaging with buildings, he elected to focus on what he called ‘architectural elements’ — an approach that brings to mind Rem Koolhaas’s project at the 2014 Venice Biennale. Kalina’s idea was to display windows and gateways on the front of the banknotes and bridges on the back — three elements that were meant to symbolize openness, cooperation and communication. Along with stylization, this elemental approach was instrumental in isolating architecture from its historical and geographical bonds, which would have contradicted the supranational ambition of the project. As noted by Koolhaas, the fundamental elements of architecture can be ‘used by any architect, anywhere, anytime’. Such breakdown then opens the possibility to ‘reconstruct the global history of each element’ (Koolhaas 2014).

The data gathered by EOS Gallup Europe played a key role in the selection process. When asked what Kalina’s banknotes ‘talked about’, 84% of the interviewees pointed to architecture. More than 60% of them found his design ‘attractive’ or ‘very attractive’, and said that it inspired confidence. The survey also endeavored to test the performance of each proposal vis-à-vis a series of binary attributes. Kalina’s proposal proved to have the best balance between ‘unity and diversity’ and between ‘past and future’ in the representation of European identity. It also tested well in the section that evaluated the gender connotation of the banknotes: the interviewees thought it had perfect balance between femininity and masculinity. The key question, however, had to do with national bias (Figure 9). Kalina’s entry was perceived as the most supranational, since more than three-fourths of the people said that it did not favor any one country or region; instead, it evoked ‘the whole of Europe’ (EOSGE 1996).

Nevertheless, shortly after the European Monetary Institute had presented the winning proposal to the public at a press conference on 13 December 1996, the issue of national bias came up again. After a few weeks, Russ Swan, the editor of the British magazine Bridge Design and Engineering, conducted a thorough investigation into Kalina’s banknotes and was able to point out a number of similarities between his designs and real bridges.

Swan was invited to talk about it on BBC’s Newsnight, and the story was quickly picked up and disseminated by a multitude of media outlets throughout the world. In his BBC interview, Swan was accompanied to the stage by the soundtrack of Mission Impossible (the chairman of the European Monetary Institute had said that it would be impossible to identify the bridges) and presented his case in front of exhibit boards with enlargements of the euro banknotes, mimicking the dynamics of a trial or, perhaps more appropriately, a legal drama. In his presentation, Swan argued that some of Kalina’s bridges did not meet the requirement of being devoid of identifiable characteristics, because he could spot details copied from the Pont de Neuilly in Paris, the Rialto in Venice and other well-known bridges (Swan 2010).

Under public pressure, the European Monetary Institute had to ask Kalina to modify his designs in order to make them less recognizable and more generic. The Working Group on Printing and Issuing a European Banknote tried to put together yet another group of ‘experts’ to oversee this process (Heinone 2015: 91–92). Voncken was the only one who agreed to take on this unique architectural consultancy. Like many other members of the feature group, Voncken had thought that Kalina’s ‘invented architecture’ would raise a lot of eyebrows: as it turned out, the problem was that it was not invented enough (Voncken 2020). In a later interview with The Wall Street Journal about the redesign of his bridges, Kalina noted: ‘I thought I had changed them enough the first time; apparently, I did not’ (Steinmetz 1998).

As highlighted in an article published by City Lab, the redesign process was facilitated by the fact that Kalina, like Luc Luycx and many of the other designers involved in the euro competition, did not elaborate his proposal by hand: ‘He was inspired by specific bridges and used a computer to combine various real-world components so as to obscure their initial identities’ (Grabar 2013). Kalina actually publicized his preference for digital technologies. Most of the newspaper articles on this topic were accompanied by a staged photograph of Kalina in his office, posing in front of two computer monitors with images of his banknotes (Figures 10 and 11).

Robert Kalina and Luc Luyxc, 1997. These almost identical, staged photographs of Kalina (left), the designer of the euro banknotes, and Luyxc (right), the designer of the common side of the euro coins, speak to the importance that was attributed to the use of computers. Source: Archives of the European Central Bank and Numismag.

The question of technology is key. Perhaps unknowingly, the action that the European Monetary Institute asked the participating designers to perform was precisely that which raster graphics software such as Photoshop had just been created to accomplish. Firstly, the entire process revolved around bi-dimensional images. More importantly, the task was to manipulate these images and, through a process of stylization, generate an original representation of elements that did not exist but looked recognizable and realistic. As illustrated by Amy Kulper, the fundamental operation of digital tools like Photoshop is to move us away from the object, while giving us the impression of moving closer to the realism of the object. The images produced by Kalina were designed to resemble a Classical aqueduct or a Gothic window (Figure 12). But, in fact, they resulted from a ‘critical move away from the object’ — our (nationally biased) history of architecture — that was facilitated and magnified by the digital turn (Kulper 2016).

While Kalina had to go ‘back to his computer’ and adjust his banknotes, the European Monetary Institute took the opportunity to look for other possible issues and, to avoid any other controversy, went so far as to hire an engineer to check the structural soundness of his designs (Steinmetz 1998). Since it is generally important for a currency to project strength and stability, the Working Group on Printing and Issuing a European Banknote wanted to make sure that these bridges would not collapse if they were actually built.

Building the Euro: Architecture as Nation-Unbuilding

In a bizarre twist of life imitating art, the Dutch artist Robin Stam took up the challenge and, right after the euro crisis of 2009, launched a project called The Bridges of Europe in the town of Spijkenisse, near Rotterdam. Almost ten years after the new banknotes had entered the wallets of more than three hundred million Europeans, this project gave an additional dimension to the struggle of bending architecture in a supranational direction, turning Kalina’s images into models for concrete buildings (Figure 13).

Robin Stam, The Bridges of Europe, 2011. Construction of the 5-euro, Classical bridge, in the Spijkenisse housing development, near Rotterdam. Source: Robin Stam.

Stam’s idea was to expose the logic behind the design of the euro banknotes: ‘Wouldn’t it be amazing if these fictional bridges suddenly turn out to exist in real life?’ (Stam 2011). In 2011, he pitched his idea to a friend in the city council of Spijkenisse, which had just started building a middle-class housing development on the outskirts of town. As is customary in the Netherlands, the site was surrounded by canals and therefore required a number of bridges for pedestrian and bicycle crossings. The city council saw it as a good way to promote the new development and decided to fund Stam’s bridges, even though they were 25% more expensive than the catalog bridges that were initially intended for the site.

In his own writings and interviews, Stam kept framing this act of retro-construction as something funny, hilarious, ironic (Griffiths 2013). In the end, his ‘joke’ cost about one million euros. For the head of the city council, however, ‘all the attention was more than worth it’ (Grabar 2013). One of the ironic aspects of this project was that the reproductions of the ‘grandiose-looking’ bridges on the banknotes were built over narrow canals. Even though they were blow-ups of pocket-size images, they still looked awkwardly small in comparison to the height of a person or a bicycle.

To enhance the effect of the project, the bridges needed to be exact replicas of Kalina’s designs, down to the color and the most inconspicuous details. For example, Stam elected to crop the edges of his little structures, because they were not visible on the bills. Overall, the bridges were built by pouring colored concrete into finely decorated wooden molds with relief patterns that gave the impression of stone or brick, except for the last two bridges, the ‘modern’ ones, which had to built out of steel (Figure 14).

Robin Stam, The Bridges of Europe, 2011. Construction of the 200-euro bridge (‘iron and glass architecture’) in the Spijkenisse housing development, near Rotterdam. Source: Robin Stam.

While the design of the euro had revolved around the idea of erasing buildings and transcending architecture into the realm of historically allusive images — an idea that aligned with one of the founding myths of postmodernism — Stam’s project aimed to turn the tables and, albeit with a (postmodernist) act of irony, put buildings back at the center of this process.10

It is worth noting that Stam is a graphic designer and, much like Kalina, has no background in architecture or engineering. Hence, unknowingly following in the footsteps of the European Monetary Institute, he assembled a ‘team of experts’ to help him put his idea into action (Grabar 2013). Remarkably, in a story that revolved around architecture, the protagonists had little or no knowledge of architecture.

At the core of Stam’s project was an interest in exposing Europe’s struggle to deal with different and opposing national identities. He referred to the euro banknotes as ‘member-state-neutral’ objects, which was why they had to be ‘fictional’ (Stam 2011). One of the outcomes of his project was that, after the transition from fiction to fact, all the bridges ended up existing in only one country, the Netherlands. Playing with this contradiction, Stam went so far as to raise the issue with the European Central Bank, which proved to have a sense of humor and replied with an official letter of approval (Allen 2011).

Discussing the difficulties of creating the euro, the head of the Deutsche Bundesbank’s Money Museum, Heike Winter, pointed out that until then banknote design had been inseparably linked with national self-image (Winter 2004). As money was seen as a means for states to construct simple messages through images and immediately have them reach the pockets of millions of people, architectural representations associated with (more or less) fictional histories of those states were often at the center of this communication.

Much has been written about the relationship between architecture and nation-building. There is also a vast literature on the role that architectural history played in this process. In his book European Architecture 1750–1890, Barry Bergdoll addresses the remarkable case of the cornerstone ceremony for Soufflot’s church of Ste-Geneviève, orchestrated by Louis XV in 1764: ‘The cornerstone contained a copy of Leroy’s History of the Form and Layout which the Christians have given their Temples from Constantine to our own Time; an Enlightenment philosophy of history literally became the cornerstone of the new building’ (Bergdoll 2001: 29–30). While the young French state relied on architecture to produce grandiose representations of its powers, it also recognized the effect of presenting said architecture as the latest (and greatest) development in a long historical progression, which embraced and appropriated a multitude of cultures. The role of Leroy’s genealogical tree of architectural plans was to elevate both Soufflot’s building and, more importantly, the seat of power that commissioned it, by giving them a historical mission.

But how do architecture and architectural history relate to the process of nation-unbuilding in Europe and the emergence of a system that, since the early 1950s, has aimed to go beyond the realm of the state? Although the architectural discourse is often accused of being too Eurocentric and too politicized, we have mostly ignored the political dynamic that, more than any other, has been transforming the European archipelago over the past seventy years: the process of European unification.

In the area of monetary unification, the area in which Europe reached its highest level of integration, architecture was recognized as the most appropriate tool for the construction of a supranational message. However, the architectural imagery of the euro banknotes had to cope with the paradoxical condition of needing to be ‘nation neutral’ and, at the same time, embedded in a historical narrative that would inevitably intersect with national dynamics (Figure 15).

Feature Selection Advisory Group, Selection of Design Features for the European Banknote Series, 1995. While putting forward a series of historical precedents, the advisory group underlined the need to avoid any ‘specific reference to any given building’ in the banknote designs. Source: Archives of the European Central Bank.

A history was needed to provide concrete models and, above all, an overarching system that would help situate fictional architecture in real time, making it seem legible and legitimate. But, except for the small group of designers and bank executives involved in the process, no one could see the materials of this history, as they would have given away the national underpinnings of this supposedly supranational endeavor.

Perhaps that is why, instead of being celebrated on the place publique like Leroy’s book, the document produced by the Feature Selection Advisory Group was marked as confidential and hidden in the archive of the European Central Bank. Not only is history as a medium embedded in the episteme of the modern nation-state, but also its content is mostly made of objects with some level of national connotation. In the postmodern, supranational order to which the European Union aspires, how can a history of architecture pass the test of political correctness?

Notes

- Ten years after the Maastricht Treaty, the euro entered into circulation on 1 January 2002, becoming the common currency of Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. [^]

- The recent controversy surrounding the proposal to enforce a single architectural style for all new federal buildings in the United States shows how issues of style still permeate the dispute between nationalism and its opponents. [^]

- The International Organization for Standardization is responsible for a standard called ISO 4217, first published in 1978, which defines the designators of current and historic currencies. [^]

- According to Hymans, two key aspects of the euro banknotes ‘push in a postmodern direction’: the absence of human figures and the decision to obscure the ‘original models there may have been for the depicted [architectural] structures’. [^]

- According to Cooper, there are several factors that distinguish postmodern systems from all others, including the blurring of the distinction between foreign and domestic affairs, the rejection of force for resolving disputes, the growing irrelevance of borders, voluntary mutual interference and surveillance. [^]

- The process of European unification officially started in 1951 with the signing of the Paris Treaty, which established the European Coal and Steel Community between Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands and West Germany. [^]

- With the expression ‘innocent eye’, Gombrich refers to the myth that images do not need to be read and that their reception does not depend on prior knowledge on the part of the beholder. [^]

- In 2002, the European Central Bank organized and hosted an exhibition of all the designs submitted to the euro competition. The catalog provides a great deal of information about the jury, the designers, their proposals and the entire competition process. [^]

- Two recent exhibitions at the Canadian Centre for Architecture have touched on the impact of Gallup on Western politics and culture: Architecture Itself and Other Postmodernist Myths (2018) and Our Happy Life: Architecture and Well-Being in the Age of Emotional Capitalism (2019). [^]

- Sylvia Lavin, Building Postmodernism, doctoral seminar at UCLA, Winter 2015. Lavin challenges the notion that postmodern architecture is about image culture and, instead, focuses on buildings — ‘the one thing postmodernity, theoretically, could not produce’. [^]

Author’s Note

I am grateful to Gundula Rakowitz, Maria Bonaiti, Laura Fregolent and all the colleagues at the University Iuav of Venice who engaged with my research. My thanks to the Archives of the European Central Bank, that provided most of the materials on which this article was constructed. I would also like to express my gratitude to the editors and peer reviewers of Architectural Histories for their valuable feedback.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Allen, K. 2011. An Uncommon Monument to the Common Currency. Spiegel International (online), 4 November. Available at https://www.spiegel.de/international/zeitgeist/euro-bridges-an-uncommon-monument-to-the-common-currency-a-795930.html [Last accessed 1 December 2020].

Bergdoll, B. 2001. European Architecture, 1750–1890. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Calligaro, O. 2013. Negotiating Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1057/9781137369901

CEC [Commission of the European Communities]. 2005. Recommendation on Common Guidelines for the National Side of Euro Circulation Coins. Official Journal of the European Union. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reco/2005/491/oj [Last accessed 1 December 2020].

Chang, M. 2009. Monetary Integration in the European Union. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-01883-0

Choay, F. 2001. The Invention of the Historic Monument. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cooper, R. 1996. The Postmodern State and the World Order. London: Demos.

Dinand, J. 2020. Interview by Sebastiano Fabbrini, 2 March.

ECB [European Central Bank]. 2003. Euro Banknote Design Exhibition. Frankfurt: European Central Bank.

EMI [European Monetary Institute]. 1996. Design Brief for the Design of a Series of Euro Banknotes. ECB Archives.

EOSGE [European Omnibus Survey Gallup Europe]. 1996. Final Report: Euro Banknotes Test Results and Comments. ECB Archives.

Foley, F. 2007. Between Force and Legitimacy: The Worldview of Robert Cooper. Florence: European University Institute.

FSAG [Feature Selection Advisory Group]. 1995. Selection of Design Features: Report of the Feature Selection Advisory Group to the European Monetary Institute’s Working Group on Printing and Issuing a European Banknote. ECB Archives.

Geary, P. 2002. The Myth of Nations: The Medieval Origins of Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Giles, L. (ed.) 2014. Italian Master Drawings from the Princeton University Art Museum. Princeton: Princeton University Art Museum.

Gombrich, E. 1960. Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Grabar, H. 2013. Europe’s Most Famous Fictional Bridges, Brought to Life. City Lab (online), 14 June. Available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-06-14/europe-s-most-famous-fictional-bridges-brought-to-life [Last accessed 1 December 2020].

Griffiths, A. 2013. Fictional Bridges on Euro Banknotes Constructed in the Netherlands. Dezeen (online), 5 June. Available at https://www.dezeen.com/2013/06/05/the-bridges-of-europe-robin-stam-copied-from-euro-banknotes/ [Last accessed 1 December 2020].

Harloe, K. 2013. Winckelmann and the Invention of Art History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199695843.001.0001

Heinonen, A. 2015. The First Euros. Frankfurt: European Central Bank.

Hobsbawm, E. 1992. Ethnicity and Nationalism in Europe Today. Anthropology Today, 8(1): 3–8. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/3032805

Hobsbawm, E and Ranger, T. (eds.). 1993. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hübsch. H. 1992. In What Style Should We Build? The German Debate on Architectural Style [1828]. Trans. by W. Herrmann. Santa Monica: Getty Publications.

Hymans, J. 2004. The Changing Color of Money: European Currency Iconography and Collective Identity. European Journal of International Relations, 10(1): 5–31. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1354066104040567

Issing, O. 2006. The Euro: A Currency without a State. Public speech, Helsinki, 24 March. Available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2006/html/sp060324.en.html [Last accessed 1 December 2020].

Koolhaas, R. 2014. Elements of Architecture. Milan: Taschen.

Kulper, A. 2016. Architecture’s Digital Turn and the Advent of Photoshop. Lecture at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, 9 June. Available at https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/articles/issues/4/origins-of-the-digital/41052/architectures-digital-turn-and-the-advent-of-photoshop [Last accessed 1 December 2020].

Luycx, L. 2001. Ready to Jangle Some New Loose Change? Deutsche Welle, 25 December.

Mulhearn, C and Vane, H. 2008. The Euro: Its Origins, Development and Prospects. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4337/9781848442887

Raento, P, et al. 2004. Striking Stories: A Political Geography of Euro Coinage. Political Geography, 23(8): 929–956. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2004.04.007

Stam, R. 2011. The Bridges of Europe. Tumblr. Available at https://thebridgesofeurope.tumblr.com/ [Last accessed 1 December 2020].

Steinmetz, G. 1998. The Euro Designer’s Art Will Have a Wide Currency. The Wall Street Journal, 7 July, p. B1.

Swan, R. 2010. The Euro. Blog. Available at http://russswan.com/about/the-euro/ [Last accessed 1 December 2020].

Terragni, G. 1931. Architettura di Stato. L’Ambrosiano, 11 February.

Toemmel, I. 2014. The European Union: What It Is and How It Works. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

TSAG [Theme Selection Advisory Group]. 1995. Interim Report to the European Monetary Institute’s Working Group on Printing and Issuing a European Banknote on the Selection of a Theme for the European Banknote Series. ECB Archives.

Van Ham, P. 2001. European Integration and the Postmodern Condition: Governance, Democracy, Identity. New York: Routledge.

Voncken, J. 2020. Interview by Sebastiano Fabbrini, 16 January.

Winter, H. 2004. The Design of Euro Banknotes. In: Proceedings of the 11th Meeting of the International Committee of Money and Banking Museums, Seoul.