Introduction

With the aim of identifying different building types, this work surveys the architecture of accommodations in Tuscany, from the 17th century to the first half of the 19th century. During this period, significant changes in the tastes and needs of travellers occurred and are reflected in Grand Tour travel literature.1 In travel accounts, reports on accommodations (inns, hotels) are usually not the main subject because the private aspects of the journey are often pushed to the background and special attention is paid instead to the description of places, monuments and lists of works of art. Nevertheless, when these descriptions are included they provide useful insight since accommodation represented a recurring issue for travellers; at the same time, this information provided tourists the opportunity to note differences between the lifestyle of their own country and that of the other countries they would be visiting. The many — usually negative — comments about early Italian travel facilities in Grand Tour literature also reveal, as suggested by Jeremy Black (1997), the tendency of travellers to prefer long stays in the main cities and short stopovers in those places where inns and hotels were only minimally acceptable. This paper tries to understand how the architecture of accommodation facilities developed during the centuries of the Grand Tour in response to a larger and more demanding crowd of travellers. Buildings situated along Tuscan roads and intended for short stays will be analysed initially, followed by a study of city hotel architecture that is regarded as a transformation of the architectural model of private noble palaces.

Accommodation on the Roads of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany

From the end of the 16th century, the accommodations available in Europe, and in Tuscany2 in particular, gradually evolved (at least along the most-travelled routes) within a simple but functional system. In the 16th century, when the fashion of the educational journey began to spread, inns were already a characteristic of all major roads in Europe. By reading travellers’ diaries and notes published between the 16th and 17th centuries, it is possible to infer that since the Middle Ages the quality of lodgings had improved very little. The first regional differences in quality seem to emerge in this period, but it is difficult to assess to what extent the perception of levels of quality was real or due to the stereotypes of the time, from which our travellers were not immune (Maczak 1992). Along the routes of the Grand Tour, the traveller could find shelter in coaching inns or taverns. In Europe, from approximately the mid-17th century, the coaching inn — sometimes called a coach house or staging inn — was a vital part of the inland transport infrastructure as an inn serving coach travellers (Gallop 2003; Richardson 1948; Pevsner 1976; and Banby 1998: 17–23). Coaching inns stabled teams of horses for stagecoaches and mail coaches and replaced tired teams with fresh teams. Some towns in Tuscany had as many as ten such inns, and rivalry amongst them was intense, not only for the income from the stagecoach operators but also for the revenue from food and drink supplied to the wealthy passengers. However, the quality of the services offered by these facilities was basic, because they were considered short stopovers along fixed routes leading to the cities and towns, where it was possible to find more spacious and comfortable accommodation (hotels, guest houses, or furnished apartments).

Travelling for education or leisure was an opportunity for a chosen few and buildings used as paid accommodation facilities slowly conformed to the demands of those who, based on their lifestyle and sense of belonging, were part of a high social class (Battilani 2001). In 1580, Michel de Montaigne arrived in Tuscany, attracted by the curative properties of the thermal waters of Bagni di Lucca, in the hope of healing from painful kidney stones.3 In his diary, he describes in detail the Italian hospitality industry, which was then mostly public houses, inns and furnished apartments of poor quality. Nonetheless, he found excellent accommodation in Tuscany, in Levanella, near Arezzo, which he compared to the best French hotels:

The inn [of Levanella] is around one mile before the village and is famous; they regard it as the best inn in Tuscany and they are right; indeed, bearing in mind the level of inns in Italy, it is one of the best. It is a place of great revelry and they say that the local nobility meets here often, just as it does at the ‘Moro’ in Paris or at Guillot in Amiens. They serve food on tin plates, which is certainly a rarity. (Montaigne 1983: 110)

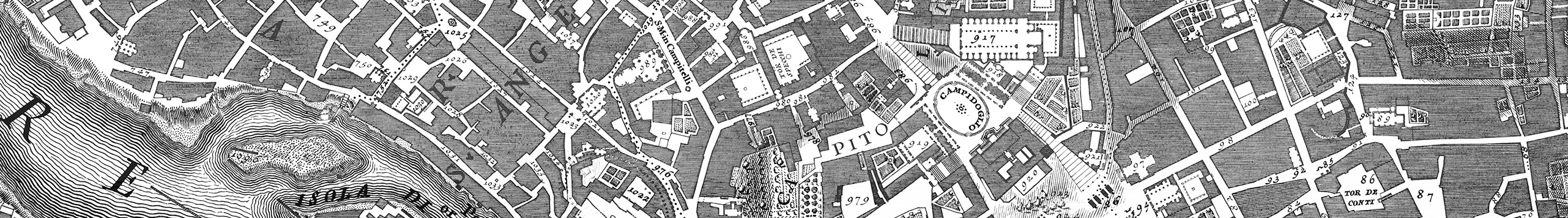

Initially, the representation of Tuscan accommodation structures coincided with the arrival of Michel de Montaigne. Between 1580 and 1595, the administration of the Grand Duchy of Florence produced a series of geographical maps, the Piante di Popoli e Strade dei Capitani di Parte Guelfa, which show the first depiction of special buildings called osterie (public houses or inns). In just the area of Florence, more than forty inns were located close to important streets and crossroads (Pansini 1989).4 These maps provide an opportunity to consider the distribution and the typology of the inns along the main roads of the Grand Duchy.

The maps show that the Via Romana, the most popular route with travellers, merchants, and pilgrims since the Middle Ages, hosted many of these buildings: the Osteria del Galluzzo (Figure 1), Osteria Montebuoni and Osteria della Fonte a Petroio, the two inns of Sambuca (Figure 2), the inn of Montecorfoli, Osteria del Bargino, the inn of Poppiano, called the Romana Osteria, and the inn of Querciola di Staggia. On the map and on the road, these inns were imposing and easily recognizable (their roofs are coloured red on the map to indicate their primary role in the hierarchy of the road network in the Grand Duchy). As in the rest of the Italian and European territories, they were characterized by signboards and large porches for horses and coaches. The inn itself was usually a simple building, often accompanied by workshops for the blacksmith, the farrier and butcher. These workshops are represented on the maps with the typical opening in the shape of a ‘T’ (Figure 3).

Osteria del Galluzzo, detail of Piante di Popoli e Strade redatte dei Capitani di Parte Guelfa (1580–1595), map number 651 (Pansini 1989).

Detail of the two osterie [inns] on the Romana road in the town of Sambuca (Pansini 1989: map 178).

Osteria del Camicia. The presence of a shop is signalled by the typical opening in the shape of a ‘T’, here in the side wall (Pansini 1989: map 106).

While inns were spreading across the territory, the state-organized coaching inn system was being developed. The Sovrintendenza Generale delle Poste (General Superintendency of Posts) was established in 1607 in Tuscany (Cantini 1802, vol. 6). In the 18th century, the House of Habsburg-Lorraine settled upon a new system of coaching inns. The first real postal law was published on March 14, 1746,5 and in 1762 the legislation was reorganized by Francesco Stefano di Lorena. In 1783, the ownership and management of the mail system passed to the Dipartimento Generale delle Poste (General Department of Posts). The gradual ‘revolution’ of the roads in Tuscany under the Lorraine government involved the improvement of services related to the transport of people, goods, and mail through the system of stazioni di posta (coaching inns) (Figure 4).

Frontispiece of the travel guide Guida per viaggiar la Toscana, second half of the 18th century (Giachi 1977).

Travelling from one coaching inn to the next was a widespread practice during the Grand Tour. By the mid-18th century, several handbooks and travel papers were published containing maps with routes, information on places where horses could be changed, and notes about the most challenging areas to pass through. With the gradual improvement of the roads came improved services related to the transport of people, goods, and correspondence through the use of poste-cavalli (coaching inns), which had been open since the 16th century along the major transit routes, called strade postali (postal roads). These buildings were strictly controlled by the state apparatus and were used to support its couriers; the services provided, at regular distances, were posts managed by postieri (postmasters) for the replacement of horses in addition to being places of accommodation for travellers (see Scarso 1996 for more information about the administrative organization of the coaching inn system in the Grand Duchy).

From an architectural viewpoint, we can identify two stages in the development of Tuscan coaching inns. Initially, they were simple buildings, mostly hybrid in terms of function and without markers of social distinction. They were located within established inns, or in buildings that already had a receptive function; the latter was the case with the post stations of Montecarelli in the Apennine area (Figures 5 and 6),6 Levane, in the area of Chianti,7 and Ricorsi in Senese.8 These public buildings could easily fulfil the need to accommodate travellers and respected basic standards. For example, they were visible from a distance and their façades displayed a sign; Grand Ducal signs were exhibited and were considered protection for travellers. Typologically, these buildings did not differ greatly from each other and could also be found serving as simple stables or barns. The most widespread architectural model — with local variations — was that of a simple, compact building with the necessary annexes, built on two or more floors. In fact, all coaching inns of Tuscany were distributed across several floors, with specialization of the internal features progressively taking place between the 17th and 18th centuries.

In the second phase of the development of coaching inns, in conjunction with a policy of expansion and improvement of the road network promoted by the government of Peter Leopold, new stations were built. These structures acceded to the social distinctions among and privacy of travellers, through the introduction of private apartments and the improvement of services and of comfort in general.

This is evident in the station within the customs house of Boscolungo, designed and built around 1780 by Bernardo Fallani, the architect of the Scrittoio delle Regie Fabbriche Granducali (Office of the Grand Ducal Royal Factories); today it is mostly structurally and functionally intact (Figure 7).

The organization of this complex coaching inn with customs facilities consists of two separate blocks facing the street. The distribution of the space is functional: porch, stables, cellar, and kitchen on the ground floor, and living rooms, bedrooms, and luoghi comodi (toilets) for guests upstairs. The block north of the street housed spaces providing services necessary for a journey and the replacement of horses. On the ground floor were separate barns and stables for the inn and the post office, as well as storehouses, a tack room, a wash house, a shed, and a drinking trough. Next to the stable for the post office, a rectory led directly to the new church of St. Leopold. On the first level of this block were kitchens and bedrooms for postilions (coachmen), a room for fodder, and barns; on the second and last floor were more barns and two bedrooms for postilions, one of which was equipped with a fireplace. The building situated south of the street housed the inn and the post and customs offices; this structure consisted of four levels with a stable, a room for wood, a cellar, and a roost in the basement. On the ground floor, a large porch provided access to the customs office, while a large, two-storey staircase provided access to the entrance hall of the inn; it aligned with two lounges containing a fireplace where travellers could enjoy a hot meal. The pantry and kitchen were located behind these areas. Two lounges were on the first level — one of these had a fireplace — along with four bedrooms (one with a fireplace, too) and the toilets. Garrets were accessible on the second floor.9 Far from being an exception, this complex arrangement of functions within a small but well-designed compound of buildings is similar to that of other coaching inns built on the new Pistoiese-Modenese Road and located in Le Piastre, Piano Asinatico e San Marcello (for drawings and documents see ASFI, Segreteria di Finanze. Affari prima del 1788, n. 496). Thus, it can be said that the new coaching inns built by the government of Lorraine, beginning in the mid-18th century, were innovative buildings. Bigger, more organized than older facilities and with a greater rationalization of space, they represent the ultimate in efficient, on-the-road Tuscan hospitality well into the 19th century.

Urban Hospitality in Florence (17th–19th Centuries)

The history of hospitality in the major cities of Tuscany has its roots in the Middle Ages. In the 13th and 14th centuries, the towns of Florence, Siena, and Pisa had paid accommodation facilities that were privately managed and hosted merchants, travellers, and pilgrims. The hotelier profession, as well as the hotel itself, gradually specialized over the centuries covered by our study in conformity to the tastes, needs and interests of travellers. A preliminary analysis of some Tuscan cities (Florence, Pisa, Livorno) between the 16th and 17th centuries suggests that most urban accommodation facilities opened inside existing dwellings and thus were not purposely built. These generally simple inns, or locande,10 were intended as basic accommodation facilities. Current research suggests that it may be pointless to try to identify a unique architectonic model for early urban accommodation structures in the Tuscan Grand Duchy due to the almost total association of these buildings with private dwellings (Gerbaldo 2006: 27–76; Brilli 2014: 147–166).

During the 18th century, however, the emergence of a travelling élite that valued ‘exclusive’ tastes as a means of social distinction led to a general transformation of accommodations. A specific interest in privacy and comfort emerged, at least in rooms for eminent guests, as well as in the quality of reception services of the accommodation facilities themselves, which led to the opening of living rooms, cafés, and other meeting spaces.11 The use of the word hotel to refer to accommodation facilities for travellers also came into use in the English language during this period (Pevsner 1976). The term hotel was thus beginning to indicate a whole series of transformations relating to the structures used for reception. By the first decades of the 19th century, a further diversification had taken place: some hotels had begun to target the most distinguished and wealthy visitors, providing rooms with fine furnishings as well as living rooms and coffee rooms for conversation; others, such as boarding houses or smaller hotels (Battilani 2001), were designed for ‘middle-class’ travellers.

In general, throughout this period, accommodation in Tuscan cities was to be found inside palaces located at strategic points in the old town centre and close to the main places of interest. This applies both to Florence, the capital of the Grand Duchy, and to smaller towns such as Siena, where the area chosen for accommodation was located near the Piazza del Campo,12 or in Lucca, where hotels were all located within the city walls.13 The progressive transformation from inn to grand hotel took place in the Grand Duchy very late compared with other major European countries such as France and England and other popular destinations in Italy such as Venice, Rome, and Naples (Denby 1998; Fraenkel and Iunius 2008; Gerbaldo 2009; Gerbaldo 2006; Gerbaldo 2014; Zaniboni 1921). In Tuscany, no new urban architecture was purposely built to receive travellers before the late 18th century; the majesty of the ancient palaces that were modified to function as hotels had been, until then, sufficient to meet the needs and tastes of more and more eclectic travellers.

Because of the fragmented nature of the documents related to the early modern period, no precise picture is possible of the concentration and quality of accommodation facilities in the cities of the Grand Duchy up to the 17th century. At the State Archives of Florence, the collection of registers of the University of Linaioli includes papers pertaining to the Arte degli Albergatori (Guild of hoteliers), which was established in Florence in 1324 (Sartini 1953: 175–250, 257–322).14 By analysing the registration books in the collection, it has been possible to understand the complex variety of accommodation facilities in the city, beginning in the first half of the 17th century. The documents provide information about the names of all members of the Arte degli Albergatori and the fees they had to pay to be considered part of the guild (Figure 8).

The registration lists provide a series of names of professionals and accommodation facilities. While these lists do not provide a precise location nor describe the type of accommodation facilities or their internal distribution of space, it is nevertheless possible to draw some conclusions about the distribution of accommodations within the city during the 17th century. The first registration book, begun in 1635, informs us of the presence of twenty-four hoteliers in the city, including five women. The areas with a higher concentration of hotels were those of Borgo San Lorenzo and Santa Maria Maggiore. The registration book of 1650 mentions forty hoteliers, including seven women. The city increased its accommodation capacity through new areas dedicated to hospitality, such as those of Borgo Ognissanti and Piazza del Grano. The lists also reveal some particularly long-lasting hotels and inns, such as the hotels del Sole, della Palla, della Campana, del Centauro, della Rondine, and del Falcone, (ASFI, Università dei Linaioli, 159, Libro degli Albergatori segnato A), all mentioned in 1635 and continuously present in the city well into the following century.

The late 18th century is also the period of the appearance of a new source, closely associated with the development of modern travel: the guidebook. Guidebooks gradually began not only to provide tourists with historic and arts-related information, but also to analyse the quality of lodgings. Boccolari’s guide (1784) puts this information at the beginning of the description of each city. For Florence, we read that ‘the best inns are that of Mr. Vannini, with apartments following the fashion of Paris, that of Monsieur Meghit in Fondachi di S. Spirito, formerly property of Monsieur Carle, the Locanda della Rossa and companions opposite to the Porta di S. Pancrazio, which provides lunch and round table’ (Boccolari 1784: 156; italics in original).

The most complete guide to hospitality services in Florence in the first half of 19th century is that by Fantozzi (1842), which mentions twenty-two hotels, most of them housed in former private palaces. Among them we find Palazzo Ricasoli, in the district of Santa Trinita, known as the Grand Hotel de New York (Figure 9)15; Palazzo Spini Feroni, transformed into the luxury Hotel d’Europe by the Hombert family in 1834 (Figure 10)16; Palazzo Bartolini Salimbeni, converted into the Hotel du Nord in 1839 (Figure 11).

Palazzo Ricasoli, in the district of Santa Trinita, known as the Grand Hotel de New York (second half of 19th century) (Pucci 1969: 57).

Palazzo Bartolini Salimbeni, converted into the Hotel du Nord in 1839 (Pucci 1969: 64).

Nearby was the Albergo del Pellicano, also known as Locanda delle Armi d’Inghilterra, which opened in Palazzo Minerbetti in Via Tornabuoni in the early 19th century.17 In Borgo Santi Apostoli, Palazzo Acciaiuoli, purchased by the lawyer Raffaello Maldura, was transformed into an inn, the adaptation involving the opening of additional windows in the facades18; in 1835 the building became the property of the aristocratic English collector W. Kennedy-Laurie and was converted into a luxury hotel called Reale dell’Arno. The large Gran Bretagna hotel, consisting of two palaces connected by a bridge, was opened in the nearby Chiasso Del Bene, which links Borgo Santi Apostoli to Lungarno Acciaiuoli. In Oltrarno, Palazzo Capponi, on Lungarno Guicciardini, was also used as an accommodation facility. At first it was known as Hotel Royal de la Toscane, but then was referred to as Hotel des Iles Britanniques. In the Piazza Soderini (now Sauro) in the Palazzo Schneiderff, the owners opened the homonymous hotel,19 whereas at the corner of Lungarno Guicciardini, the Hotel d’Inghilterra was opened in the Palazzo Medici.

The prestige of these facilities was such that, in 1806, J. G. Lemaistre, visiting Italy after the Peace of Amiens, considered that in Florence ‘people could find better accommodation than any other country in the continent’ (Lemaistre 1806: 433). Indeed, the good reputation of the services provided in the growing number of Florentine hotels that were installed in early modern residential palazzi contributed to making the Tuscan city a favoured destination, not only for scholars and art lovers but also for those who wished to heal from diseases such as tuberculosis or ‘consumption’. English and American travellers in Florence chose their dwellings with special attention. Whether it was a room ‘with a view’ (Forster 1908) or a rented apartment,20 among the available facilities they especially targeted the ancient palaces, which were refitted almost exclusively with all modern amenities and were often managed by their compatriots.

The Palazzo Bartolini Salimbeni functioned as the home of the Salimbeni family until the first half of the 19th century.21 In 1839, part of the building was leased to Francesco Ponsson and Adelaide Herbeln, who transformed it into a hotel under the name Hotel du Nord. The plans attached to an appraisal made by the engineer Cianferoni between 1858 and 1860 reveal how the building was adapted to its new function, mainly in the interior distribution of space.22 The main entrance, overlooking Piazza S. Trinita, gave access to a vestibule which opened onto a large central hall; on the ground floor there was also a large dining room and a series of other spaces put into service as bedrooms, cloakrooms, shops, cafés, and lounges. The magnificent grand staircase led to a piano nobile where a vestibule, once providing access to the gran salone, now opened onto apartments for families and private rooms. The distribution of the second floor reflected that of the piano nobile, while the mezzanines and the third floor were used exclusively as service areas and servants’ rooms. In the basement were cellars, storage areas and the large kitchen serving the whole palace, and each floor had sanitary facilities (toilets and baths) (ASFI, Tribunale di Prima Istanza, Busta 695, n. 1901) (Figures 12 and 13). This conversion took place with scarcely any alteration to the building’s exterior, which was respected and appreciated for its Renaissance architecture, and thus with no significant impact on the surrounding urban environment.

Conclusion

The purpose of this research has been to understand how different types of accommodations for travellers developed over the centuries of the Grand Tour in Tuscany, from the gradual improvement of inns and coaching inns situated along the roads of the Grand Duchy to the development of city hotels. Between the 17th and 19th centuries, accommodation facilities located along the roads became part of the actual territorial infrastructure. Innkeepers gradually improved their interiors and the services they offered to meet the demands of a growing number of travellers. Coaching inns, which were an essential part of the infrastructure for horse-drawn transportation, lost their significance after the middle of the 19th century, following the rise of railways. Some of these buildings were then converted into taverns while, in the majority of cases (especially in southern Tuscany), they were simply reused as small farms or private houses.

Urban hotel facilities, by contrast, became specialised only by the end of the 18th century, as accommodation services began to be adapted for a specific class of traveller — those for whom the Renaissance palace represented the ideals of good taste and ‘noble’ living. The grand hotels developing in Florence during the first decades of the 19th century retained the large halls and reception rooms of existing urban palaces for use as ‘public’ areas, separated from private areas that hosted the bedrooms and apartments. This conversion of dwellings into accommodation facilities could take place with little alteration to the buildings’ exteriors. Often, however, in the changes of ownership following the decadence of the Medici and Lorraine governments, foreigners bought and converted these palaces, restoring these old houses in an imaginary ‘Florentine’ style, with discreet additions, reconstructions and embellishments according to modern (and often English) taste.

Notes

- The Grand Tour was the traditional trip around Europe undertaken mainly by young, upper-class, European men of means, or by those of more humble origin who could find a sponsor. The custom flourished from about 1660 until the advent of large-scale rail transport in the 1840s. Beginning with the pioneering work done by D’Ancona (1889), many studies have been carried out on the Grand Tour; see Brilli (2015), Brilli (2014), De Seta (2014), De Seta (1992), and Gerbaldo (2009). This paper is the summary of more extensive research done by the author for her PhD dissertation. [^]

- Nominally a state of the Holy Roman Empire until the Treaty of Campo Formio in 1797, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany was ruled by the House of Medici until the extinction of its senior branch in 1737. Francis Stephen of Lorraine, a cognatic descendant of the Medici, succeeded the family. His descendants ruled and resided in the Grand Duchy until 1859, with one interruption (1801–1814), when Napoleon Bonaparte gave Tuscany to the House of Bourbon-Parma. [^]

- M. E. de Montaigne (1533–1592) travelled through France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy, from 1580 to 1581, and established himself at Bagni di Lucca where he benefited from the waters. He is traditionally regarded as a precursor of the fashion for travelling in Italy and of the Grand Tour. He kept a journal in which he recorded regional differences and customs and a variety of personal episodes (Montaigne 1983). [^]

- Pansini (1989) demonstrates that these plans are notable for their topographical and cadastral interest; they report — with a perspective and view-based language that is typical of Renaissance cartography — features specific to each building type (such as workshops, tabernacles, churches), at times providing more specific details on their architecture and size. [^]

- The law was regulated by the decree of 16 June 1746: Regolamento universale da osservarsi da’ corrieri, procacci, postieri, vetturini ec. [^]

- An old inn was converted for the station of Montecarelli, approved on 1 April 1752, as reported in the State Archives of Florence (ASFI), Segreteria di Finanze. Affari prima del 1788, n. 647 (Dipartimento Generale delle Poste: Direzione di Firenze, Poste in luoghi subalterni, file Montecarelli. [^]

- ASFI, Segreteria di Finanze. Affari prima del 1788, n. 646 (Dipartimento Generale delle Poste: Direzione di Firenze, Poste in luoghi subalterni, file Levane): ‘L’edificio postale di Levane congiuntamente all’osteria e chiesa annessavi furono in origine una proprietà dello scrittoio delle Regie Possessioni e formarono parte della reale fattoria di Levane il di cui affittuario ritirava le pigioni dependenti dal fabbricato della posta e dell’osteria. Piacque in seguito a Sua Altezza Reale di approvare che l’edifizio inserviente alla posta ed osteria passasse in proprietà del Dipartimento Generale delle Poste nel 17 maggio 1783’. [^]

- ASFI, Segreteria di Finanze. Affari prima del 1788, n. 648. In the town of Ricorsi, at least one inn existed since the late Middle Ages and it was within that inn that the post-station opened ‘on the 30 of June 1716, following the supplications and petitions by Ottavio Bandinelli, gentleman from Siena, whose lineage gave him the use of the said inn’. [^]

- The book of building expenses is in ASFI, Amministrazione Generale Regie Rendite 1768–1808, n. 567. Lists of manual labourers and workers (bricklayers, woodcutters, blacksmiths, and carters) as well as accounts regarding construction are provided from June 1782 up to completion of the works. [^]

- The Italian term locanda (inn) derives from the Latin locare, which means to lease or rent. [^]

- Pevsner (1976: 169) notes that the difference between a hotel and an inn is a matter of size, and of the presence in hotels of public spaces and public rooms. [^]

- The history of hospitality in Siena has its roots in the Middle Ages, when a good number of inns and taverns were located both inside and outside the city walls (Tuliani 1994). Since the late 16th century, travellers’ accounts usually praised the excellent hospitality and services received in this city (Brilli 1986). [^]

- Hotels and inns in Lucca were mainly situated along Via Fillungo and in the area between Piazza San Michele and Piazza Grande; the della Luna, del Moro, and del Biancone inns are mentioned in 18th century documents. The tavern and inn della Campana, located in the square with the same name and already mentioned in 16th-century documents, was particularly well known; from its courtyard (then called Piazza della Posta), the stagecoaches of the postal service arrived and departed (Boccolari 1784). [^]

- The fonds of hoteliers in ASFI includes four codes of statutes: statutes dated 1324 and 1334, in Latin; a 1338 statute in the vernacular and Latin, which was updated until 1509; and one last code, probably belonging to the same period, completely in the vernacular. Matricole’s books are also available, thanks to which an extensive overview of accommodations in the city is provided, with facilities attested to, from 1639 to 1713. [^]

- Historical Archive of the Municipality of Florence (ASCF), n. 1191, Stime Restorini 1783, c. 8; according to estimates made by the magistrate, in the palace of Giovanni Ricasoli Zanchini at Ponte alla Carraia (present-day Piazza Goldoni) ‘a part of the house’ was used as a hotel and was known at that time as English House. Among its guests was the writer Hester Lynch Thrale-Piozzi, who held a sort of literary academy there between 1784 and 1786. During the following century, the building was occupied by the Nuova York hotel (also called New York hotel, or Grand Hotel de New York), chosen mainly by Americans visiting Florence (for example, the American poet William Cullen Bryant, who stayed at the hotel in 1858, where he met Nathaniel Hawthorne). [^]

- Among the Palace’s guests: the Prince of Metternich (1838), the Grand Duke Alexander of Russia (1838), the Hungarian composer Franz Liszt (1838), and the American poet James Russell Lowell (1856). In 1838, the hotel was handed over to one of the Homberts’ nephews and was greatly criticised by English travellers who were disappointed with the standard of the hotel management given the price paid (Jousiffe 1840: 44). [^]

- The Albergo del Pellicano is recommended as an ‘excellent inn run by Gasperini, where dinners are cooked and served better than in any other hotel’ (Starke 1820: 81). In 1840, Captain Jousiffe praised the care and respectability that the manager, Mister Gasparini, continued to maintain at the facility. In the eyes of English travellers, the innkeeper was also famous for his ability to repair and build carriages. [^]

- ASCF, Comunità di Firenze, Deliberazioni magistrali e consiliari, 4 dicembre 1820–8 marzo 1821. [^]

- Antonio Schneiderff, probably a native of Lorraine, bought the palace owned by Sir Balj Ottaviano de’ Medici in 1802 in the district of Santo Spirito on Lungarno Guicciardini. In 1805, the building was already in use as an inn, and it was gradually enlarged following the purchase of other nearby buildings. As a result of the investments made, the palace (called the Schneiderff Hotel) became one of the most reputable Florentine hotels during the first half of the 1800s. It was the choice of very diverse foreign travellers; in 1819, Ducos was fascinated by the hotel because ‘travellers were assigned to servants who spoke their language and it was possible to rest on spotless beds and eat at a refined table’, as he wrote in Itinéraire et souvenirs d’un voyage en Italie (1829). The Description of a View of the City of Florence, of Robert Burford (Burford 1832) introduced the Schneiderff as ‘a capacious and magnificent establishment, well provided with every comfort and luxury, at every season of the year, and at very moderated charges’. [^]

- Travellers choosing to stay in an apartment preferred the historic districts of Santa Maria Novella, Santa Croce, and Oltrarno, where they preferred to rent whole areas of palaces owned by the ancient Florentine aristocracy. These buildings, with their grand and austere apartments, could be rented seasonally at very low prices and ‘adjusted’ with furnishings that, in choice and taste, inevitably reminded these Anglophone travellers of their homeland. [^]

- Palazzo Bartolini Salimbeni, the first palace in Florence built according to the ‘Roman’ Renaissance, was erected by the architect Baccio d’Agnolo between 1520 and 1523. The Bartolini-Salimbeni family lived in the palace until the early 19th century. In 1839 it became the Hotel du Nord, and in 1863 it was acquired by the Pio di Savoia princes and split between different owners. Restored in 1961, the palace is now a private property. [^]

- Documentary and iconographic material now in the State Archives of Florence has been published by Bartolini Salimbeni (1978). [^]

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Unpublished Sources

ASCF (Historical Archive of the Municipality of Florence) Archivio Fotografico Comunità di Firenze, Deliberazioni magistrali e consiliari Stime Restorini.

ASFI (State Archives of Florence) Amministrazione Generale Regie Rendite 1768–1808. Piante dello Scrittoio delle Regie Possessioni Scrittoio Fortezze e Fabbriche, Fabbriche Lorenesi Segreteria di Finanze, Affari prima del 1788 Tribunale di Prima Istanza Università dei Linaioli.

Published Sources

Banby, E 1998 Grand Hotels. London: Reaction Books.

Bartolini Salimbeni, L 1978 Una fabbrica fiorentina di Baccio d’Agnolo: le vicende costruttive del palazzo Bartolini Salimbeni attraverso i documenti d’archivio. Palladio, 7–28. Serie 3.

Battilani, P 2001 Vacanze di pochi vacanze di tutti. L’evoluzione del turismo europeo. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Black, J 1997 The British Abroad: The Grand Tour in the Eighteenth Century. Stroud: Sutton Publishing Ltd.

Boccolari, D 1784 Nuova descrizione di tutte le città dell’Europa e di tutte le cose più notabili e rare. Lucca: Benedini.

Brilli, A 1986 Viaggiatori stranieri in terra di Siena. Siena: Monte dei Paschi di Siena.

Brilli, A 2014 Il grande racconto del viaggio in Italia. Itinerari di ieri per viaggiatori di oggi. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Brilli, A 2015 All’epoca del Grand Tour: viaggiatori stranieri lungo le vie consolari. Bologna: Minerva.

Burford, R 1832 Description of a View of the City of Florence, and the Surrounding Country, Now Exhibiting at the Panorama, Leicester Square. Painted by the proprietor Robert Burford, from Drawings Taken by Himself in 1830. London: T. Brettell.

Cantini, L 1802 Legislazione toscana, VI. Firenze: Stamperia Albizziniana.

D’Ancona, A 1889 Saggio di una bibliografia ragionata dei viaggi e delle descrizioni d’Italia e dei costumi italiani in lingue straniere. In: D’Ancona, A (ed.) L’Italia alla fine del secolo XVI: giornale del viaggio di Michele de Montaigne in Italia nel 1580 e 1581, Città di Castello: Lapi. 3–31.

Denby, E 1998 Grand Hotels, Reality and Illusion: An Architectural and Social History. Zwolle: Waanders Publishers.

Ducos, B J 1829 Itinéraire et souvenirs d’un voyage en Italie en 1819 et 1820. Paris: Dondey Dupré.

Fantozzi, F 1842 Nuova guida ovvero descrizione storico artistico critica della città e contorni di Firenze. Firenze: Giuseppe e fratelli Ducci.

Forster, E M 1908 A Room with a View. London: Edward Arnold.

Fraenkel, S and Iunius, R F 2008 Industrie de l’accueil. Environnement et management. Bruxelles: De Boeck.

Gallop, R 2003 Coaching Era: Stage and Mail Coach Travel in and Around Bath, Bristol and Somerset. Coachmen and Travellers, Inns and Journeys, Highlights and Hazzards. London: Fiducia Press.

Gerbaldo, P 2006 L’ospitalità nel viaggio moderno. Evoluzione, sociabilità, risorsa. Perugia: Morlacchi.

Gerbaldo, P 2009 Dal Grand Tour al Grand Hôtel. Ospitalità, lusso e distinzione sociale nel turismo moderno. Perugia: Morlacchi.

Gerbaldo, P 2014 Alta hotellerie e turismo moderno. Percorsi storici, economici e sociali dell’ospitalità europea (XVIII–XX secolo). Perugia: Morlacchi.

Giachi, A 1977 Guida per viaggiar la Toscana. Firenze: Istituto Geografico Militare.

Jousiffe, C 1840 A Road-Book for Travellers in Italy. 2nd ed. Brussels: Meline, Cans and Co.

Lemaistre, J G 1806 Travels After the Peace of Amiens, Through Parts of France, Switzerland, Italy and Germany. London: J. Johnson.

Maczak, A 1992 Viaggi e viaggiatori nell’Europa moderna. Bari: Laterza.

Montaigne, M 1983 Montaigne’s Travel Journal. Frame, D M (ed.). San Francisco: North Point Press.

Pansini, G 1989 Piante di popoli e strade: capitani di Parte Guelfa 1580–1595, 2. Firenze: Olschki.

Pevsner, N 1976 A History of Building Types. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Pucci, E 1969 Com’era Firenze 100 anni fa. Firenze: Bonechi.

Richardson, A E 1948 The Old Inns of England. 5th ed. London: Batsford.

Sartini, F 1953 Statuti dell’Arte degli Albergatori della città e contado di Firenze. Firenze: Olschki.

Scarso, F 1996 L’organizzazione postale nel Granducato di Toscana (1681–1808). Unpublished thesis (PhD), University Federico II of Naples.

Starke, M 1820 Travels on the Continent: Written for the Use and Particular Information of Travellers. London: John Murray.

Tuliani, M 1994 Osti, avventori, malandrini: alberghi, locande e taverne a Siena e nel suo contado tra Trecento e Quattrocento. Siena: Protagon editori toscani.

Zaniboni, E 1921 Alberghi italiani e viaggiatori stranieri (sec. XIII–XVIII). Napoli: Detken & Rocholl.